Colombia Gulf Clan Gets Terrorist Tag as Fentanyl Fever Rises

Washington’s terrorist designation of Colombia’s Clan del Golfo collides with President Donald Trump’s fentanyl crackdown and offshore strikes. For President Gustavo Petro’s “total peace” gamble, the timing is brutal, threatening talks, migration routes, and regional sovereignty from Urabá to the Darién Gap.

Peace Talks Meet an American Red Line

In Urabá, northern Colombia’s gateway to the Caribbean, authority is often felt before it is seen. The Clan del Golfo—also called the Gulf Clan—has turned routes into power, moving cocaine outward and collecting “taxes” that shape everyday travel.

The U.S. Treasury Department has added the group to its list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs), the BBC reported. The step was followed within hours of President Trump signing an order classifying fentanyl as a “weapon of mass destruction.” Colombia’s cocaine war is being reframed through an opioid lens.

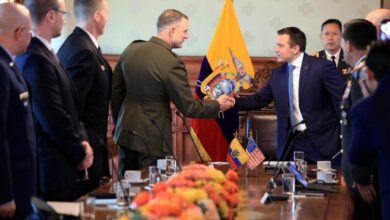

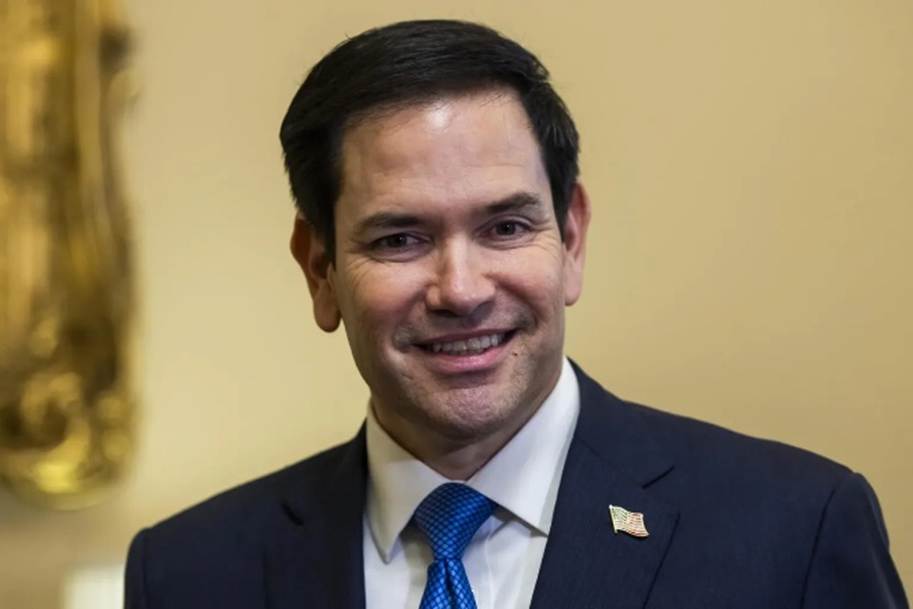

The BBC noted that leader Dairo Úsuga was arrested in 2021, but the network carried on under Chiquito Malo. With thousands of members, it is considered Colombia’s largest cocaine-trafficking gang, supplying the United States and Europe and profiting from migrant smuggling through the Darién Gap into Panama. Marco Rubio, per the BBC, blamed it for attacks on officials, security forces, and civilians. The U.S. list already includes the National Liberation Army (ELN) and two dissident groups that broke from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) after the 2016 peace deal.

For Petro, who promised “total peace,” the timing is punishing. Less than two weeks earlier, the BBC reported, his government reached a landmark agreement with the Clan del Golfo in Doha to begin laying down arms. It included an understanding that members would not be extradited to the United States. With other talks stalled, it looked like progress—until the FTO tag threatened to criminalize contact and deepen already acrimonious ties.

Maritime Strikes and the Arithmetic of Force

Meanwhile, the crackdown has turned lethal at sea. The BBC reported more than 20 U.S. strikes on suspected drug boats in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Over 90 people were killed. Some legal experts say the operations breach the law. For coastal communities, an “interdiction” headline often translates into a funeral. It adds another reason to distrust distant promises.

Petro has called the strikes “murder,” the BBC reported, and Rubio labeled him a “lunatic.” Trump, quoted by the BBC, has warned of “strikes on land” against “narco-terrorists,” singling out Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro and the Cartel of the Suns. But he also hinted at Colombia: “Colombia has at least three cocaine factories.” Later, he added, “But it’s not only land strikes on Venezuela, but it’s also land strikes on horrible people that are bringing in drugs and killing our people.”

Fentanyl Fear and Latin American Fallout

The fentanyl emergency in the United States is brutal: the BBC cited more than 110,000 drug-related deaths in 2023, though fatal overdoses fell by 25% in 2024. Trump argues the strikes save lives, saying each hit “saves 25,000 American lives,” but the BBC reported U.S. officials have offered no evidence that the targeted boats carried fentanyl. Fentanyl—about 50 times as potent as heroin—does not originate in Colombia or Venezuela, experts have noted, complicating a strategy that hits cocaine routes while invoking opioid terror.

The executive order points to a twin-track approach: continue striking cocaine supply lines while expanding authority to fight fentanyl smuggling. Studies discussed in The Lancet and the International Journal of Drug Policy emphasize that overdose waves follow treatment access and inequality as much as interdiction. Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum, the BBC reported, urged addressing the causes of drug use and warned that fentanyl is also a legal hospital painkiller. Meanwhile, the FTO label freezes any assets in U.S. institutions. It enables prosecutions for “material support,” even of U.S. citizens, powers that could turn Colombia’s peace table into a legal minefield.

For communities in Urabá and along the Darién Gap, the minefield is not theoretical. A more rigid U.S. posture can splinter armed groups, punish civilians branded “collaborators,” and shift violence to new routes. Colombia has lived through decades of U.S.-backed drug strategy; Petro’s wager is to shrink incentives to fight. If Washington rewards escalation, the costs land first in the tropics.

Also Read: Chile Elects Kast Again: Crime and Memory Shape A Presidency