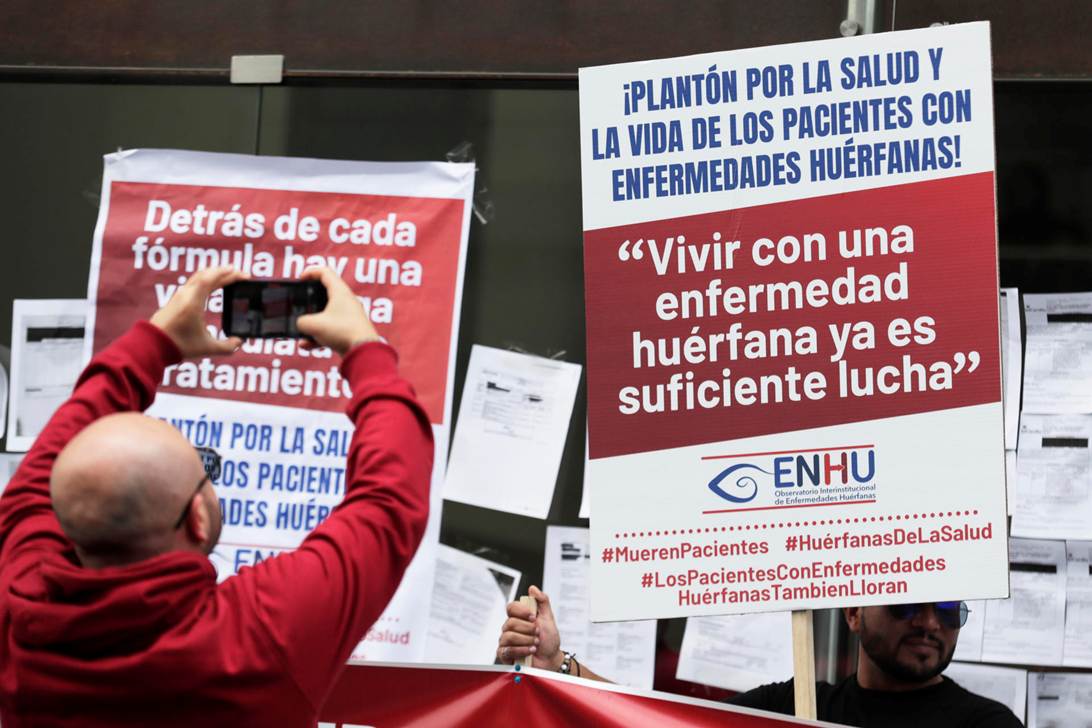

Colombia Health Breakdown Leaves Families Improvising Care Outside Insurers’ Doors

Outside Colombia’s largest health insurer, a mother steadies her disabled son as expired prescriptions pile up amid protests, highlighting how policy failure turns into daily suffering for families.

A Morning of Waiting and Paper

The micro scene unfolds on a sidewalk in front of Nueva EPS’s main headquarters in Bogotá. It is not loud. It is heavy. María Rubio wraps her son in blankets and secures him with belts in his wheelchair. The air is cool, and paper edges curl in her hands. She holds expired medication orders, fanned like proof, while traffic hums nearby. People pass on their way to work. The building does not move.

Her son has cerebral palsy, microcephaly, and multiple disabilities. He belongs to the group of high-cost patients whose treatments are authorized yet delivered irregularly, relatives and organizations say, as they protest outside the country’s largest health insurer. The everyday observation implied by the scene is brutal in its simplicity: authorization does not equal delivery. A stamp does not become a pill.

“Everything is authorized, but they do not disburse the resources and the pharmacy does not deliver,” María told EFE, lifting the bundle of orders. She explains she has gone from one dispensing point to another without success, even though her son needs daily antiepileptics.

The trouble is what happens next. María improvises, feeling the weight of exhaustion and sacrifice as she cares for her son, knowing each adjustment can worsen his condition.

“No hay suministros,” she says later, and the phrase hangs over the sidewalk.

When Interruptions Become Absence

Victoria Salazar, who heads the board of the Interinstitutional Observatory of Rare Diseases, says patients have faced constant interruptions since last year, a situation that worsened in December. Now, she says, it is no longer just interruptions.

“There are no supplies. Nueva EPS is not buying the treatments patients need,” Salazar told EFE, adding that months of procedures and promises have produced no concrete evidence of a solution.

The government has acknowledged the health system crisis, but despite interventions, patients continue to suffer, feeling the system’s failure firsthand.

Official data indicate insurers carry significant debt owed to hospitals, clinics, and drug suppliers. The effect is cumulative. When payments stall, deliveries stall. Chronic, rare, and high-cost patients feel it first and longest.

What this does is turn policy disputes into household logistics. Who can drive to another pharmacy? Who can borrow a bottle? Who can skip a dose?

Courts, Journals, and Kitchen Remedies

The diagnosis has reached academic pages. A recent article in the British Medical Journal described Colombia’s health system as undergoing a “deep deterioration,” citing medication shortages, treatment interruptions, and growing access barriers following public policy decisions. The Health Ministry rejected that report as biased and lacking technical rigor, arguing the crisis is structural and not attributable solely to the current administration. It said resources allocated to the sector rose in real terms between 2022 and 2026, equivalent to 25 trillion pesos.

Numbers travel easily. Pills do not.

The National Health Observatory estimates that nearly 20 percent of avoidable deaths are linked to health system failures, a reality felt deeply by families like Rocío’s, whose child’s medication delays threaten her daughter’s life.

Rocío González, mother of an eight-year-old girl with pulmonary hypertension, faces ongoing medication shortages, her frustration growing as she fights for her child’s right to health.

“I have filed tutelas, contempt actions, and nothing happens. I have to organize raffles and ask for help,” she told EFE.

One of her daughter’s medications can cost between two and four million pesos per box. Another, cheaper, lasts only two days. Like María, Rocío left her job to care for her child. She now survives on occasional work. The rhythm of her life is measured in doses and deadlines.

The wager here is whether judicial pressure can substitute for administrative capacity. Families keep filing. The system keeps lagging.

Back outside Nueva EPS, María adjusts the blanket again. She says she has no life. It is not a metaphor. It is a schedule erased by caregiving.

For caregivers, this is not a technical debate about financing models or governance charts. It is a daily negotiation with gravity, and authorities must prioritize patient dignity by ensuring the system delivers on its promises.

Also Read: Colombian Plane Crash Exposes the Hidden Cost of Regional Connectivity