Colombia’s Battle of Boyacá: The Riverbank Where a Republic Was Born and a Monarchy Fell

On a fog-laced afternoon in 1819, a teenage fusilier near a narrow bridge in Boyacá captured a Spanish general—and in that moment, the crumbling Spanish crown in South America gave way to a people’s republic that has lasted two centuries and counting.

Where Geography Became Strategy and Terrain Made History

Long before cannons shook the hills of Boyacá, the royal road that wound from the Caribbean port of Santa Marta to Bogotá served as the empire’s main artery, threading soldiers, merchants, and taxes through the backbone of Nueva Granada. Its bends were familiar to the Spanish. That was part of their undoing.

In her 2024 monograph for the Universidad de los Andes, military geographer Diana Pabón González reveals just how narrow that road was—barely four meters wide in places, slick with Andean clay that turned artillery transport into a nightmare. Spanish officers, confident in their logistical superiority, saw that road as a shortcut. General Simón Bolívar saw a trap.

At dawn on August 7, 1819, Bolívar led his army out of Tunja, hugging the high ridgeline of El Tobal to stay hidden. The Spanish, under José Mariano Barreiro, trudged through deep ravines along the Motavita track, their cannons bogged down by mud and their cavalry split by the Teatinos River.

As retired Colonel Carlos Céspedes told EFE, “Bolívar moved like a chess master. He sacrificed the vanguard to draw the Spanish in—and when they committed, he sent his queen.” That queen was his main force, hidden behind the crest and ready to strike.

It worked. Geography bent to the will of strategy, and the royalist army walked into a canyon they would not walk out of.

A Battle Measured in Musket Smoke and Memory

The shooting began around two in the afternoon. Somewhere near Casa de Teja, amid stone walls and ripening cornfields, someone pulled a trigger—and two simultaneous battles erupted. The vanguards clashed near the bridge, while the main patriot body came pouring down the slope.

According to 19th-century chronicler José Manuel Restrepo, Colonel Joaquín París and his riflemen advanced fast and hard, dislodging elite Spanish cazadores with brutal precision. Meanwhile, Bolívar’s right-hand man, Francisco de Paula Santander, moved east to cut the Spanish escape route.

Academic debate still lingers over who struck first. In 1948, historian William F. Sharp credited Santander. More recent scholarship by María Clara Saladín leans toward Bolívar. But the outcome is beyond dispute.

As Spanish infantry tried to regroup, Venezuelan lancer Juan José Rondón and his riders smashed into their flank. The Numancia battalion—a once-proud royalist unit—crumbled. The cannon fell silent. Soldiers fled into the woods or dropped their muskets and surrendered.

Andrés Beltrán, a historian at Universidad Nacional, studied the original muster rolls and found that desertion doubled after the battle. By the end of the day, over 1,600 Spanish soldiers surrendered, more than 200 lay dead, and just 66 patriots were lost.

And in the quiet afterward, a teenage boy stepped into history. Pedro Pascasio Martínez, age 17, captured Barreiro himself. The monarchy’s strongest arm in the Americas ended that day not with a bang, but in the firm grip of a farmer’s son.

When Gunfire Gave Way to Government

What makes Boyacá more than a battlefield is what came next. Within 48 hours, word galloped to Bogotá. Viceroy Juan de Sámano, hearing of the rout, fled in disguise. Royal officials scattered. The entire colonial structure collapsed without another shot.

Historian Víctor M. Uribe-Uran calls it a “uniquely bloodless state collapse.” Bolívar moved quickly. He entered the capital on August 10, was named Santander vice president, and laid the foundation for republican rule.

The ripple effects didn’t stop at Colombia’s borders. British journalist John W. Stevenson, writing for The Times of London, reported that “Spain has lost its sword arm in America.” That article caught the eye of British investors. By 1822, they were backing Gran Colombia’s first sovereign loan, as detailed by Rory Miller in Britain and Latin America in the Nineteenth Century.

Even in Washington, the news registered. Two years later, the Monroe Doctrine declared the Americas off-limits to European recolonization. Boyacá gave that doctrine weight. A musket duel by a riverbank had, almost overnight, shifted the geopolitical axis of the Western Hemisphere.

At home, it did something deeper. The fall of the Spanish regime ushered in the Cúcuta Convention in 1821, where new leaders embedded popular sovereignty into law. Renán Silva describes it as a “cultural earthquake.” Indigenous fighters returned home not as subjects, but as citizens. Though inequality endured, the monopoly on power by peninsulares was broken—not by decree, but by blood and belief.

Wikimedia Commons

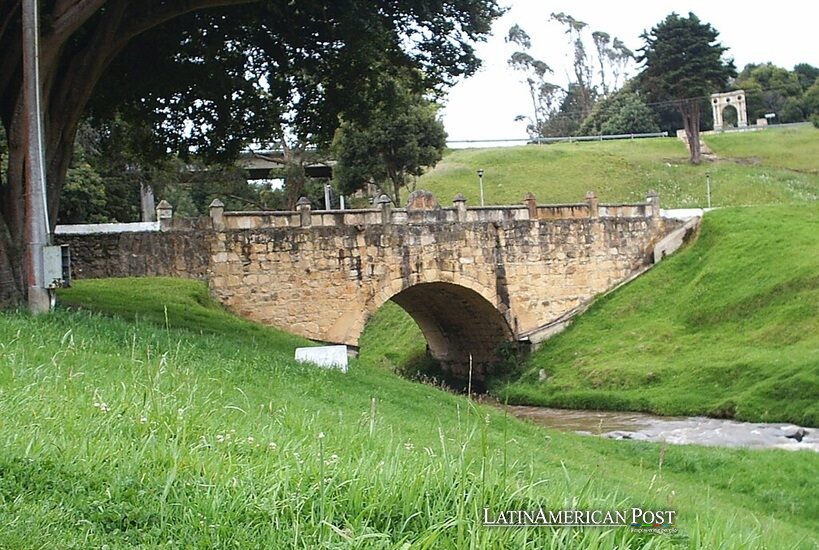

A Bridge of Stone, a Bridge of Story

Every August 7, the old Boyacá Bridge, now preserved as a national monument, fills with cadets in pressed uniforms, diplomats with wreaths, and schoolchildren with flags. The ceremonies are choreographed, yes—but they matter.

“Boyacá isn’t about glory,” said cultural anthropologist Margarita Marín in a 2023 EFE interview. “It’s about consensus. It’s a reminder that Colombia only wins when it pulls together.”

That sentiment echoes Benedict Anderson’s theory of imagined communities. For a country of coastal cities, mountain villages, and Amazon outposts, Boyacá is a mythic moment all can claim. Not because it was perfect—but because it proved possible.

Still, the narrative evolves. Revisionist scholars like Germán Arciniegas lionized Bolívar as a military genius. Newer voices, like Charles Esdaile and Jeremy Adelman, focus on Spanish strategic errors and the critical role of local Indigenous and peasant support. Environmental historian Claudia Leal adds yet another layer: August fog, altitude sickness, and terrain fatigue played decisive roles, too.

These debates don’t diminish Boyacá’s place in the national imagination—they enrich it. They remind Colombians that generals didn’t just pave the road to sovereignty, but walked by farmers, volunteers, and weathered horses.

Today, the bridge is also a pilgrimage site. Veterans of later wars—civil, ideological, or narcotic—come to honor those who fought in a different kind of conflict. Tourists leave handwritten notes. Children recite speeches. Cyclists in the Vuelta a Boyacá climb El Tobal in homage, chasing ghosts up the same slope where patriots once marched.

In this layered landscape, Boyacá endures not as legend, but as a living memory.

Colombia marks Boyacá’s anniversary not because it sealed independence alone, but because it taught Colombians what unity under fire could look like. The monarchy fell not in Madrid, but at a muddy river’s edge, where a boy with a musket captured an empire.

In every flag hoisted over the bridge, every anthem played in schools, and every name carved into stone, Colombians don’t just remember—they re-sign their contract with the republic, forged in smoke, sealed in blood, and still beating, two centuries later.

Also Read: Fear Shuts Doors on Atlanta’s Latin Corridor, but Buford Highway Refuses to Disappear

—Academic works cited include David Bushnell’s The Making of Modern Colombia, Malcolm Deas’s essays in The Andean World, Rory Miller’s Britain and Latin America in the Nineteenth Century, and Renán Silva’s Entre la espada y la pluma. Quotations from Carlos Céspedes and Margarita Marín were provided to EFE.