Former Venezuelan Strongman Places All Faith in Washington “Pit Bull” for Manhattan Immunity Fight

In Manhattan, defense lawyer Barry Pollack, nicknamed Pit Bull, stood beside ousted Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro days after a raid. Prosecutors press drug-trafficking charges. The case tests issues such as sovereignty (a nation’s independent authority), extradition (the transfer of a suspect from one jurisdiction to another), and U.S. power, echoing Latin America’s memory from Caracas to Washington.

The Man You Hire When the Trap Snaps Shut

Some lawyers arrive with theatrics; others like a locksmith. Barry Pollack is the latter: soft-spoken, discreet, and known for gnawing on a case with relentless patience and persistence. Early in his career, peers coined his nickname—half-jest, half-warning: Pit Bull. For those staring at severe outcomes in American courtrooms, he’s the lawyer you call after the door locks, and you need to find the hinge.

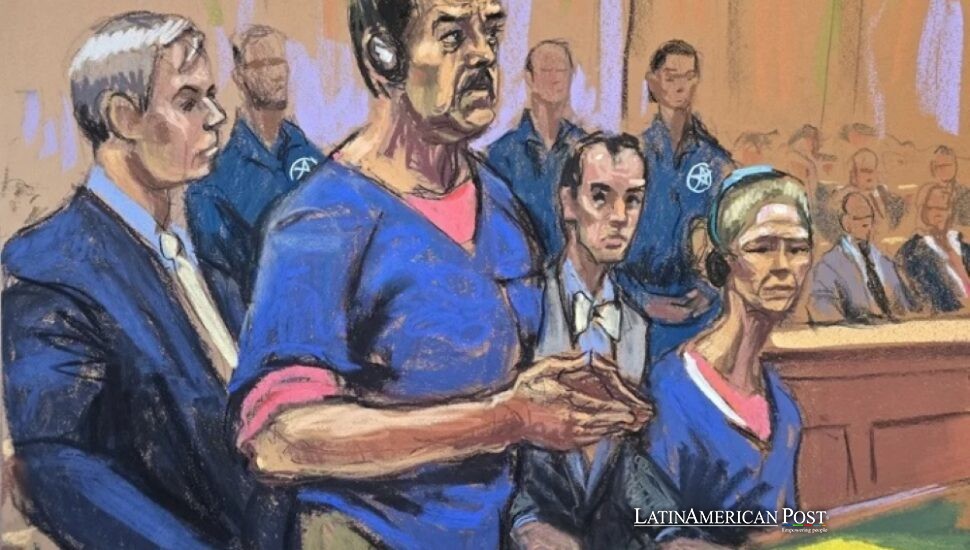

On Monday, in a Manhattan federal courtroom, Pollack stood beside Nicolás Maduro, described as 6 feet 3 inches, outspoken and muscular—almost a head taller than his lawyer. Prosecutors allege Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were seized in an overnight military raid and transported to the United States less than 48 hours before the hearing to answer drug-trafficking charges. In Latin America, where arrests often blur with geopolitics, the episode feels like more than a legal process. It plays as a confrontation between systems.

This feature is based on reporting, quotes, and interviews published by The Wall Street Journal journalists Lydia Wheeler and C. Ryan Barber. John Elwood of Arnold & Porter, who worked with Pollack early in their careers, remarked, “It’s remarkable he is not better known.” People who know him say the silence around his name is part of his method: he doesn’t build celebrity; he builds records.

Not A President in Court, But A Claim of Sovereignty

You’re right to flag the title. In the text you provided, he’s described as ousted, and in a U.S. courtroom, he is not automatically treated as a sitting head of state. The legal fight turns on Pollack’s argument that his client is entitled to the immunities and privileges of a sovereign leader. That distinction matters, because “president” is not just a label—it’s a recognition question, and recognition is where politics and law collide.

At the arraignment, Pollack told the judge he plans to challenge the legality of Maduro’s capture and argue that his client is entitled to immunity as head of a sovereign state. When the judge began setting deadlines, Pollack pushed back, saying the case would be complex. The next hearing was set for mid-March.

The immunity argument arrives with a heavy regional echo. The report points to Manuel Noriega, the former Panamanian strongman who raised a similar claim after the U.S. invaded Panama and captured him in 1989. A federal appeals court sided with prosecutors who said the United States hadn’t recognized Noriega as the legitimate head of Panama. A precedent (a previous legal decision used as an example) was set. “That’s obviously the very first and most important part of the case,” said Frank Rubino, who represented Noriega. For Pollack, the precedent isn’t a footnote—it’s a fence he has to climb with precision.

Pollack, a partner at Harris St. Laurent & Wechsler, filed notice representing Maduro just hours before the hearing. It remains unclear how he was retained, and he did not reply to requests for comment. In a case where every word risks propaganda, such restraint serves as armor.

Pollack is a Georgetown Law alum and college basketball fan now in his early 60s who began at Miller, Cassidy, Larroca & Lewin, a boutique white-collar defense firm known for producing top-tier lawyers, including three sitting Supreme Court justices. Colleagues there gave him the nickname “Pit Bull.” “A little alliteration was probably involved as well—‘Pit Bull Pollack,’” said Stephen Braga.

The Long-Game Defender with A Record of Unlikely Exits

His most famous modern win came with Julian Assange. Pollack negotiated the plea deal that freed the WikiLeaks founder from a British prison after a legal fight that spanned more than a decade. Assange faced 18 counts tied to releasing classified information and hacking a military computer, then pleaded guilty to one Espionage Act count while the government agreed to time served.

He has also secured an acquittal for Michael Krautz, a former Enron Corp. executive charged after Enron’s 2001 collapse, and helped win back-to-back mistrials for Rickie Blake, one of 10 chicken-company officials repeatedly prosecuted for alleged price fixing before charges were dropped in 2022. Jonathan Lopez, the former federal prosecutor who tried Krautz in 2006, said Pollack isn’t a “burn-the-house-down” defense counsel. He doesn’t need spectacles to be dangerous.

In a 2022 interview on David Oscar Markus’s “For the Defense” podcast, Pollack described his craft with blunt humility. “Pretty much everything I do in the courtroom I’ve plagiarized from somebody,” he said. That line reads differently now. In the Maduro case, the borrowings will be from precedent, procedure, and every available sliver of doctrine that can slow the machine down.

And that is the real “Pit Bull” mythology: not saving someone with a heroic speech, but buying time, forcing scrutiny, and making the state prove every step of the way. For Maduro, whether he is treated as a leader, an ex-leader, or simply a defendant may ultimately hinge on whether Pollack can persuade the court that sovereignty still clings to him—even here, even now, even in Manhattan.

Also Read: Venezuelan Diosdado Cabello’s Long Shadow Grows After Years Without Spotlight