Latin American indigenous people fight for the survival of their languages

Dozens of indigenous languages in Latin America are rapidly disappearing due to discrimination, forced displacement and technology, leaving behind a tangle of ancient cultures

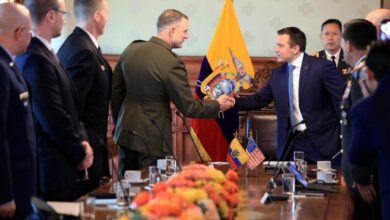

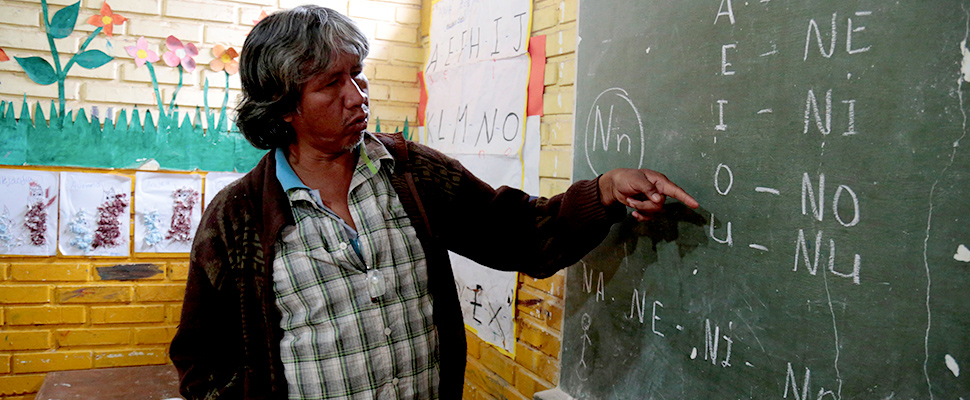

Teacher Blas Duarte shows letters in the Maka language at a school used by children of the Paraguayan ethnic group Maka, in Mariano Roque Alonso, Paraguay, July 18, 2019/ Reuters/ Jorge Adorno

Reuters | Diego Oré and Lizbeth Diaz

Listen to this article

When she went to school in the border city Tecate, Josefina Meza thought that her classmates wanted to be her friends because they repeated a phrase in Spanish, although she did not understand it.

Leer en español: Indígenas latinoamericanos luchan por la supervivencia de sus lenguas

At recess, while talking with his brother in Kumiai – a threatened indigenous language – they were called "Pinches indios" (Lousy indians), one of the strongest and most discriminatory insults used in Mexico.

"I was asking my brother what that word of 'the Indians' meant," recalled the indigenous, silver-haired, 72-year-old activist in the remote Valle de las Palmas community, half an hour from the U.S. border.

"'Maybe they say they want to be our friends,' I told my brother. But when I started to speak Spanish more and talk to them, I realized that it was an insult," she added, ensuring that the elders of her community stopped teaching their tongue to avoid discrimination.

Like the Kumiai, which only 381 people speak according to official figures, dozens of indigenous languages in Latin America are rapidly disappearing due to discrimination, forced displacement and technology, leaving behind a bunch of ancient cultures.

In 2019, a year dedicated to indigenous languages, Unesco, the UN organization for education, science and culture, has set a task against the clock: working hand in hand with governments and native peoples to rescue their endangered languages and revitalize those threatened.

But the task is not easy: one of every five indigenous peoples in Latin America has already lost their native language and by 2030, it is estimated that Brazil – the country with the largest amount of indigenous languages in the region – runs the risk of losing a third of its more than 180 languages. In Mexico, almost 60% of its 68 languages are about to disappear, according to official figures.

In Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Central America the picture is no different. While Aymara, Guarani and Quechua enjoy good health, the same is not true with other languages spoken by indigenous people.

The representative of Unesco in Mexico, Frédéric Vacheron, told Reuters that the extinction of languages is a "natural process" but assured that when a language ceases to exist "it is not only words that disappear; it is a worldview, a cultural wealth, a way viewing the world."

Also read: 'Orange Is the New Black' offers fans a way to give back

"OUR LANGUAGES DO NOT DIE, THEY KILL THEM"

The struggle for the survival of native languages is not new. Since the end of the 15th century, when the Spanish and Portuguese conquered America, the Amerindian languages were condemned to the background.

In 1770, Carlos III, then king of Spain, abolished them and ordered to seize all documents in vernacular languages.

Some 600 survived but as time goes by they have fewer followers and about 170 of them are severely threatened: the only record of contact with their speakers dates back to 20 years ago, in some cases.

"Languages are at risk of disappearance due to phenomena that are linked to globalization, the lack of an educational system that values them and the discrimination that still exists," said Vacheron, at UNESCO since 1996.

Gasodá Suruí, an anthropologist from the Suruí-Paíter tribe, in the Amazon rainforest of Brazil, said that modernity and technology threaten his language, the almost extinct Tupí-mondé, which has about 200 speakers and in which there are no words to refer to the internet, telephone, computer or car.

"We feel threatened in all aspects: cultural, environmental, territorial and linguistic. We still dominate Tupi-Monde, but we are forgetting many of the words we need," he confessed and explained that in the village where he lives, they speak Portuguese.

In the last five centuries, more than 1,000 languages disappeared in Brazil. In 1988, the Brazilian State recognized that indigenous people have the right to use their native languages.

Since then there have been advances: thousands of indigenous teachers were trained to teach children, an inventory of linguistic diversity was created and universities, museums and research centers documented endangered languages.

But the big debt remains on a daily basis, indigenous activists interviewed by Reuters said. As much as the native languages are recognized, in Brazil, Mexico and most of the countries in the region, it is almost impossible to study a career or complete a legal procedure in one of them.

In February, from the tribune of the Mexican Congress, the indigenous activist Yasnaya Aguilar accused the State policies for being the main responsible in the disappearance of several native languages of her country.

"Even though the laws have changed, our languages continue to be discriminated against," said Aguilar, a Mixe speaker, the mother tongue of some 90,000 people in southwest Mexico. "Our languages do not die, they kill them. The Mexican State has erased them. The unique thought, the unique culture, the unique State, with the water of its name erases them," she added.

Also read: The wildcat goldminers doomed by their toxic trade

ÑUQANCHIK

In 1996, former Congressman José Linares won a public contest to apply new technologies to education in Peru.

At 76, the economist recalled that he initially had problems implementing the project in one of the 12 schools assigned to him, because the vast majority of children in a school in the Peruvian Andes only spoke Quechua.

And the Logo program with which he was to teach them was in Spanish. Indignant, Linares commanded a team that translated it into Quechua, a language spoken by more than 10 million people in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

"But, with all the efforts that were made, not much happened afterwards … as it happens to many things in Peru," Linares confessed to Reuters at his home in Lima, facing the sea.

Then, the philanthropist hosted Quechua-speaking students in his institute baptized in honor of Wernher von Braun, the German engineer who designed the rocket that took the man to the moon. From there he has achieved educational quality records and some of his students are translating the Scratch programming language, successor of Logo, into Quechua.

"You have to improve Quechua and ensure that Quechua speakers can live with it," said Linares, who has tried to show the State a dictionary of digital literacy in Quechua, with the idea of providing the Inca language with words that it does not have in the areas of science and technology.

That same State launched in 2016 "ñuqanchik" (we), the first Quechua news broadcast on state radio and television. A year afterwards it did the same with Aymara, the second most spoken native language in Peru and, at the end of 2018, it launched a cultural program in the Asháninca language.

"The fact of giving them the same hierarchy in the aspect of presence in the media with national reach has allowed not only a revaluation but a reinvigoration of languages," said Hugo Colla, president of the state National Institute of Radio and Television (IRTP).

Despite this, there is still discrimination in Peru.

"They tell you, 'Why are you going to learn Quechua if everything comes in Spanish or English?'," confessed Hugo Ramos, 26, who studied and now teaches at Linares' von Braun Institute.

You may be interested in: Sewing a way out of sex work in Spain

GUARANÍ AND NÁHUATL, TWO ANTAGONIC STORIES

Guaraní, one of the two official languages of Paraguay along with Spanish, is spoken by some 12 million people in South America and has survived the passage of time, in part, thanks to the historical isolation of the Mediterranean country.

Today, nine out of 10 Paraguayans speak it: it is common to hear it in the street, in the media and in Congress debates.

But other languages, such as Guana or Maka are threatened.

"Our greatest struggle is to try to give it greater status and try to get some regulation so that these indigenous languages also have resources to be studied," said Ivonne Gaona, of the Directorate of Indigenous Education of the Ministry of Education and Science of Paraguay.

Gaona explained that the biggest challenge is the implementation of their literacy, since many lack an alphabet.

In Mexico, Nahuatl has had a history of glories and disenchantments. From the fifth century until the arrival of the Spaniards, the language passed over others and ended up becoming the Mesoamerica's lingua franca, a region that extends from the southern half of Mexico to Costa Rica.

The Spanish conquerors grammatized Nahuatl, which until then had no Latin spelling: they wrote chronicles, poetic works and administrative documents making it one of the most documented and studied languages in America.

But it began to lose speakers as Spanish spread across the continent. Despite this, Europeans continued to use Nahuatl for educational purposes through missionaries, bringing their tongues to regions where they had no influence before.

Although it is the most widely spoken indigenous language in Mexico, with about 1.5 million speakers, discrimination has caused some parents not to teach it to their children.

"My parents have taught me a little, but I don't master it well," confessed Miguel Escobar, a senior student at a school in Ecatepec, a municipality adjacent to the capital.

"I would like to have learned more because when I go with my grandparents I don't understand them, just one or two words, but I would like to have a conversation," the young man lamented, perhaps ignoring that Nahuatl has lent Spanish about 200 words, for example 'apapachar', "to caress with the soul".