Honduras Elections Amid Gunfire, Grief, Fear, And Fragile Democracy

On the eve of Honduras’s elections, campaign songs mixed with gunshots, a five-year-old boy died in his grandmother’s arms, and millions prepared to vote under a prolonged state of exception that critics call democracy’s own anesthesia in slow motion today.

A Child’s Promise Cut Down After A Campaign Rally

In Río Helado, Arnol Caled’s dreams of becoming a police officer and building homes ended abruptly with gunfire, reminding readers of how political violence endangers children and stirs compassion.

Earlier that day, Arnol had traveled with his mother, grandmother, and other relatives to a political rally of the ruling Libertad y Refundación (Libre) party in the village of La Cuesta, in the western department of Santa Bárbara. The vehicle taking them home, a double-cabin work truck apparently owned by a legislator, was crowded with family and neighbors returning to their scattered homes in the hills.

According to Arnol’s mother, Rosita Díaz, they were tired but happy as they drove back toward Río Helado. Then, somewhere on that road, shots rang out. “We heard about five gunshots, without knowing where they were coming from,” she told EFE, her voice breaking. One round tore into the cab and struck Arnol in the head. Nearby, a fourteen-year-old girl was wounded.

The boy died in his grandmother’s arms inside the truck. In their small adobe house, Rosita — a homemaker and coffee picker — showed EFE the little toy car she had bought him just two weeks earlier in the town of Santa Bárbara, and the rubber boots he had worn for the trip to La Cuesta, where he would lose his life. A few meters from the home, next to a tree, lay the remains of his first bicycle and a bright yellow toy horse. Arnol had just been enrolled to start his first year of preparatory school in 2026. Now the only trace of that future is a stack of papers and a grieving family.

For Hondurans, Arnol’s death exemplifies how ongoing political violence and the state of exception threaten children’s safety, education, and future opportunities, underscoring the urgent need to protect human rights and foster a safer environment for the next generation.

Voting Under A State Of Exception Turned Routine

In Honduras, the election process under a prolonged state of exception underscores a serious threat to democracy, making political violence and restrictions more alarming for the audience.

Since December 2022, a partial state of exception has restricted fundamental rights, such as the rights to move and assemble, in 226 of 298 municipalities, undermining democratic participation in elections.

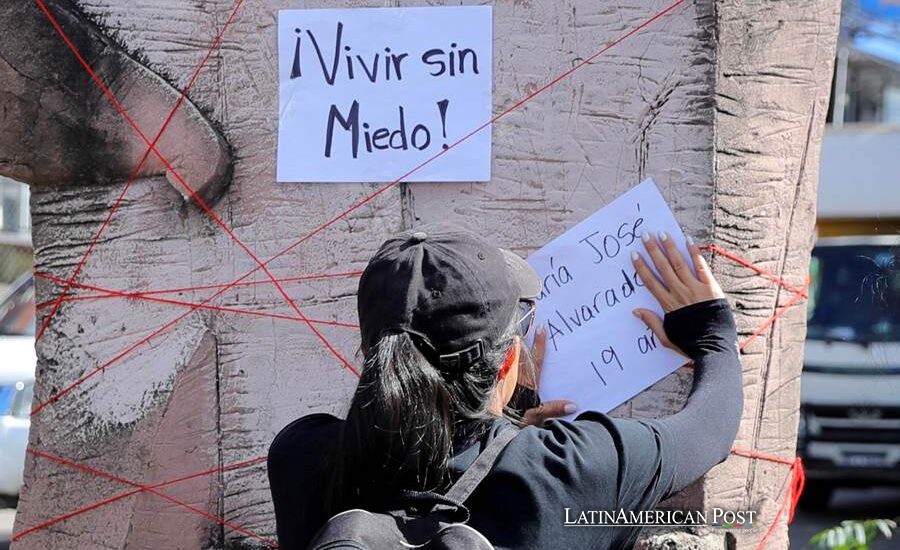

“Honduras is approaching general elections skewered on a hat that no country aspiring to call itself democratic should tolerate: an electoral process under a state of exception,” wrote Gabriela Castellanos, executive director of the Consejo Nacional Anticorrupción (CNA), in a blunt message on social media, cited by EFE. What was supposed to be an emergency measure, she warned, had turned into “norm, routine, legal anesthesia.”

Since December 2022, the state of exception has not only restricted rights but also coincided with targeted violence against political activists, candidates, and community leaders in regions like Santa Bárbara and Yoro, highlighting a broader threat to democratic participation and human rights.

The numbers tell their own story. In 2025 alone, at least four people were killed in crimes linked to political violence, Sánchez acknowledged, even as he stressed that not all had a strictly political motive. For a country of just over ten million inhabitants, four murders tied to elections are enough to keep people looking over their shoulders on the way to the polling station.

Candidates, Judges, And Women In Politics Under Threat

The list of victims reads like a cross-section of Honduran politics. In February, two mayoral candidates from the National Party were gunned down in the northern departments of Atlántida and Yoro. In July, armed men assassinated a sitting mayor from the western department of Intibucá, also from the National Party. In September, the violence crossed party lines again when a congressional candidate from the ruling Libre party in Yoro was killed.

Beyond the murders, there have been persistent reports of threats and intimidation against activists and local leaders from all three major parties: Nacional, Liberal, and Libre. The presidential campaigns, observers note, have featured more insults and fearmongering than concrete proposals.

Threats against election officials, including counselors and magistrates, highlight the pervasive intimidation that chills voters and underscores the fragile state of electoral integrity, raising alarm for the audience.

For Carmen Julia Fajardo, dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), the situation is “alarming.” “The curve is going up,” she told EFE, describing a rising tide of political violence that is both physical and symbolic. Women in politics, she added, are being targeted with particular fury, facing attacks that mix misogyny with partisan hatred. Fajardo called for a deeper culture of respect among political leaders, something that feels in short supply in a campaign where insults often land louder than ideas.

A Country Voting Through Fear, Fatigue, And Fragile Hope

On Sunday, despite fears and fatigue, more than six million Hondurans still chose to vote, holding onto hope for change amid a fragile democracy.

In communities like Río Helado, Rosita Díaz and her family faced grief instead of slogans. Their youngest child had been registered for school, but would never wear his uniform. In the cities, many voters weighed fear of gangs against fear of the state’s expanded powers. Some remembered that the state of exception was sold as a temporary fix; now it risked becoming part of the furniture.

Castellanos’s phrase about “legal anesthesia” captured a broader mood. After years of corruption scandals, gang extortion, migration crises, and broken promises, a portion of the population no longer expected elections to bring much change. Others still clung to the belief that a ballot, even cast under the shadow of soldiers and curfews, was worth something.

Honduras walked into this vote with open wounds: a child’s coffin in a rural village, mayors and candidates gunned down, judges threatened, and rights formally suspended in most of the country. Yet people still lined up, voter ID in hand, under the sun and the rain.

The question hanging over the day was not only who would win, but whether the country could begin to step back from a political culture in which bullets, threats, and emergency decrees have become normal. Between the samba of campaign caravans and the silence of fresh graves, Hondurans went to the polls hoping, at the very least, that the next four years would ask less of their fear and more of their hope.

Also Read: El Salvador’s Jesuit Case Is Stuck Again, and Time Is Becoming an Accomplice