Latin America Ties: Congo Conflict Shakes Mineral Trade

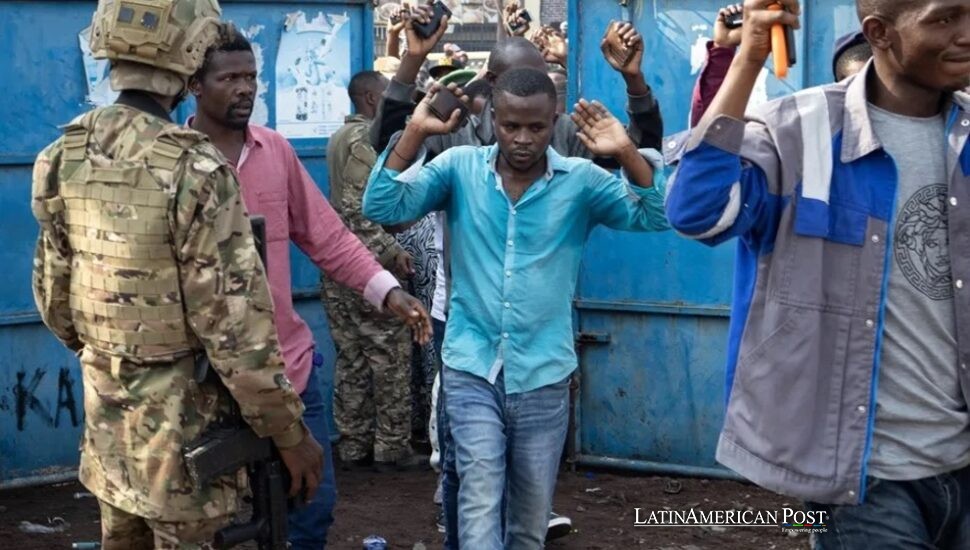

In the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo, advancement by the M23 rebel faction makes the situation worse. The conflict has reasons for ethnic disputes that have existed for a long time. It is affected by plans to take minerals and claims that Rwanda is involved. Such violence affects the world. The impact of this is felt far away, even in Latin America.

Deep-Rooted Tensions and the Rise of M23

At the heart of this complex conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the M23 rebel group, which traces its origins back to 2012. Named for a peace agreement signed on March 23, 2009—a deal rebels claim was never fully honored—the group re-emerged in 2021 after nearly a decade of dormancy. Its revival has upended fragile peace accords, reignited regional hostilities, and put a spotlight on the eastern DRC’s troubled legacy.

The M23 is mainly made up of Tutsis. They left Rwanda during or after the 1994 genocide. The initial goal was to keep Tutsi groups safe in Congo. The protection sought was against the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR). Hutu extremists were part of this group. At the time of the Rwandan genocide, these individuals did a lot of cruel things. Over time, however, the M23’s objectives have broadened. Armed with better organization and more sophisticated weaponry, it now strives to gain strategic control over mineral-rich areas in North and South Kivu.

The reawakened rebellion unleashed a humanitarian crisis. Congolese authorities attribute more than 8,000 deaths to the conflict, while tens of thousands of people have been displaced in North and South Kivu, according to United Nations (UN) estimates. Significant urban areas, such as Goma and Bukavu, have, at times, been under M23 control. This contested the administration’s authority in a territory. That area has a history of ethnic conflict and brutality that is driven by resources.

Paul Nantulya, a researcher at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington, highlights how the M23 has evolved. It is no longer solely a rebel force with grievances; it has become politically active and part of the larger Alliance Río Congo, once threatening to march on the capital, Kinshasa, to force change. Its transformation from a purely military outfit to a multi-pronged movement has made negotiation and diplomacy more complex.

Rwanda’s Alleged Involvement and Coveted Minerals

Complicating matters is the allegation—voiced by the UN, the United States, the European Union, and other entities—that Rwanda supports the M23. While Rwanda denies direct backing, multiple reports suggest that Rwandan troops have trained M23 fighters, supplied them with weapons, and even maintain a presence of 3,000 to 4,000 soldiers in Congolese territory. These claims stem from UN expert findings, which also detail how the rebels smuggle valuable resources across the Rwanda-DRC border.

Minerals lie at the heart of this conflict. Eastern DRC holds one of the world’s largest deposits of coltan—a critical component in electronics such as smartphones, laptops, and electric vehicle batteries. Beyond coltan, this region boasts reserves of gold, tin, copper, cobalt, and other high-demand commodities vital to modern global supply chains. According to Congolese Ministry of Mines data, North and South Kivu alone exported over 851 tons of coltan in 2024, valued at nearly 20 million dollars.

Given these stakes, control of mining sites translates directly into political and military power. M23, through the occupation of important areas, is able to gain money from unlawful mineral sales. It channels them by way of Rwanda or using other networks in the area. Kigali has denied taking part in this activity. Experts such as Nantulya argue that the president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, has much power regarding the ways these items move and their final destinations.

Rwanda views the danger from the FDLR as a key reason for military actions in the DRC. The government in Kigali says it must keep its borders secure from the remaining Hutu fighters. These fighters planned and performed the genocide in 1994. Some claim that Rwanda’s involvement in eastern Congo is about more than just defense. Some suggest Rwanda aims to have more influence over important assets.

In December 2024, heightened scrutiny led Western nations, including the United States and the United Kingdom, to impose sanctions on Rwanda. The European Union halted defense consultations with Kigali and began reviewing its Memorandum of Understanding on Material Resources—a framework intended to ensure ethically sourced minerals enter European markets. The government of the Congo, in the time between events, sent requests to prominent sports groups. The requests asked that organizations, such as the National Basketball Association and football clubs Arsenal and Paris Saint-Germain, stop their sponsorship deals with Rwanda. The reason cited was Rwanda’s supposed involvement in the existing conflict.

Why It Matters for Latin America

A far-away issue in Central Africa might appear unconnected to Latin America. In a world that is more and more linked, what occurs in the DRC can have effects across continents. There are several methods by which this might happen.

Global Minerals and Technology: Latin American countries, such as Chile, Peru, and Bolivia, are also major mineral producers, particularly of lithium and copper. Instability in the DRC can shift global supply chains, affecting commodity prices for resources used in similar high-tech applications. If the DRC’s coltan or cobalt supplies fluctuate due to conflict, the tech and automotive industries might look more intensely toward Latin American suppliers. This can spark both opportunities and challenges—for instance, increased investment in resource extraction, but also heightened scrutiny over labor and environmental practices.

International Norms and Security: Many Latin American nations have participated in UN peacekeeping missions and diplomatic initiatives aimed at promoting conflict resolution. A major crisis return in the DRC brings up questions regarding how well international peacekeeping works. If the M23’s actions show that groups can go against global agreements and face minor impact, this might cause more insurgencies to occur. Such encouragement could spread to areas within Latin America. These areas deal with narcotics organizations, political uprisings, or ongoing land conflicts.

Human Rights and Governance: The crisis highlights themes familiar to parts of Latin America—inequality, corruption, and historical grievances fueling armed movements. Experts suggest that the Democratic Republic of Congo’s “defective” governance, as Nantulya states, creates a situation where militias and external powers are able to misuse resources. Equivalent governance issues occur in regions of Latin America. A restricted governmental presence allows illegal mining and deforestation. These similarities highlight that general insights into resource control and dishonesty next to rebuilding the following conflict apply globally.

Looking ahead, the UN Security Council has explicitly called for Rwanda to cease support for the M23 and withdraw any troops from Congolese territory. The Congolese Armed Forces, for their part, have been instructed to sever ties with groups like the FDLR. Enforcement of these directives remains fraught, given the DRC’s sprawling geography and the complex mosaic of armed factions.

Experts like Nantulya advocate for deeper involvement by the African Union to craft a regional solution and possibly deploy a peacekeeping force far larger than the 16,000–20,000 UN troops currently in the DRC. If this conflict worsens, it might resemble the “Second Congo War” from 1998–2003. That war involved many African nations and caused more than five million deaths.

For Latin America, the DRC situation shows clearly how local conflicts may affect the world. As technology demands intensify, minerals like coltan and cobalt become essential commodities, and disruptions in their supply chains can push industries to look for new sources—including those in Latin America. Furthermore, the conflict raises cautionary tales about corruption, ethnic tensions, and governance failures.

Also Read: Mexico’s Tequila Industry Braces for Potential 25% U.S. Tariffs

In the end, what happened in North and South Kivu shows how modern economies and politics are connected. A rebel group that made advances in eastern Congo can create effects far away, affecting resource markets in Latin America. The situation also influences views in diplomacy. It gives both warnings and instructions on dealing with internal conflict, protecting the rights of minorities, and controlling important resources. The fate of the M23 insurgency and Rwanda’s involvement will undoubtedly shape not just Africa’s Great Lakes region but broader global strategies on conflict, commerce, and humanitarian intervention.