Latin American Armies Face Trump’s Shadow Seeking Unseen Shields Now

After U.S. strikes on Venezuela and the seizure of Nicolás Maduro, Donald Trump warned Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico. Across the region, generals and civilians ask the same question: how do you deter a superpower without inviting disaster into your streets.

The Imbalance Everyone Can Measure

In Latin America, defense is rarely imagined as a clean battlefield line, two flags facing off under a neutral sky. It is imagined as a cost. It is the price a stronger power must pay—in legitimacy, in time, in political fallout—before it decides a country is worth “fixing.” That is why the weekend strike on Venezuela, followed by the reported abduction of President Nicolás Maduro, landed like a cold message in every capital that has ever studied the old hemispheric playbook.

On January 4, 2026, as he returned to Washington, DC aboard Air Force One, President Donald Trump escalated the moment from one country to a region, threatening action against Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico unless they “get their act together,” framing it as a fight against drug trafficking and a defense of U.S. interests in the Western Hemisphere. In Latin capitals, the phrasing mattered less than the signal: the strongest military on earth had just demonstrated it could cross the threshold from pressure to force.

If the question is “Can Latin America defend itself in a standard war?” the numbers answer with brutal clarity. The United States spends more on its military than the total budgets of the next ten largest military spenders combined, and its 2025 defense budget was $895bn, around 3.1 percent of GDP. In the 2025 Global Firepower rankings cited in the original report, Brazil is the region’s strongest military at 11th globally; Mexico sits at 32nd, Colombia at 46th, Venezuela at 50th, and Cuba at 67th. In planes, ships, tanks, and budgets, the gap isn’t a gap—it’s a different planet.

So the real story becomes this: when conventional balance is impossible, deterrence turns psychological and political. Latin American governments look for ways to make intervention messy, morally costly, and strategically unrewarding. The aim is not “victory” in the cinematic sense. The aim is to keep the powerful from believing they can win quickly, cleanly, and without consequence.

Irregular Forces, Real Influence

In the original report’s clearest—and most unsettling—line, the one area where the threatened countries can claim an advantage is not their regular armies, but their paramilitary or irregular forces: organized groups that can operate outside conventional chains of command and outside the neat logic of state-to-state war. In Latin America, these forces are not a theory. They are memory—sometimes born from revolutions, sometimes from counterinsurgency, sometimes from organized crime, often from all three.

Cuba is presented as the most striking case: it has the world’s third largest paramilitary force, more than 1.14 million members, including state-controlled militias and neighborhood defense structures. The largest, the Territorial Troops Militia, functions as a civilian reserve designed to assist the regular army in external threats or internal crises. Even without matching U.S. aircraft carriers, a mass reserve changes one calculation: how hard it is to control territory after the first strike is over.

Venezuela offers a different kind of irregular power, rooted in politics. Pro-government armed civilian groups known as “colectivos” have been accused of enforcing political control and intimidating opponents, operating outside formal military structures but often seen as tolerated or supported by the state, particularly during unrest under Maduro. Their significance in a deterrence conversation is dark and simple: they can blur the line between government security and street-level enforcement, turning a crisis into a domestic labyrinth for any outsider trying to impose order.

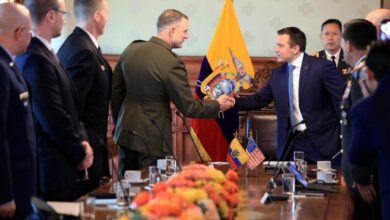

Colombia carries the longest shadow. Right-wing paramilitary groups emerged in the 1980s to fight left-wing rebels; though officially demobilized in the mid-2000s, many reappeared as criminal or neo-paramilitary organizations active in rural areas. The report notes an uncomfortable origin story: early groups were organized with involvement from the Colombian military following guidance from U.S. counterinsurgency advisers during the Cold War. The deterrence lesson is bitter: irregular forces, once encouraged as tools, can become permanent features of a country’s security landscape—and permanent complications for anyone who wants a clean intervention narrative.

Mexico illustrates the most destabilizing form of irregular power: heavily armed drug cartels operating as de facto paramilitary forces. Groups like the Zetas, originally formed by former soldiers, possess military-grade weapons and exert territorial control, often outgunning local police and challenging the state. This is not “defense” in a patriotic sense; it is a warning that in parts of the region, the state’s monopoly on force is already contested. For Washington, that contest is often cited as the justification for action. For Latin American societies, it is exactly why escalation risks turning “security” into prolonged chaos.

History As Warning, Diplomacy As Defense

If irregular forces are the grim tool of last resort, diplomacy is the first line many governments reach for, because it widens the battlefield beyond missiles and into legitimacy. The region’s fear is not only what the U.S. can do, but what it can normalize. That fear comes from a long ledger: the Banana Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the promise of the 1934 Good Neighbor Policy and its later betrayals, the Cold War era when the CIA, founded in 1947, financed operations to overthrow elected governments. The one formal U.S. invasion cited in the report—Panama in 1989, “Operation Just Cause,” aimed at removing Manuel Noriega—remains a regional reference point for how fast a justification can become an occupation, and how a single country can be made into an example.

That history doesn’t automatically produce unity; Latin America is too politically diverse for that. But it does produce a shared instinct: when the strongest actor moves, smaller states try to shift the arena—from force to law, from speed to scrutiny, from shock to solidarity. The more the crisis is debated in international forums and framed as a question of sovereignty, the harder it becomes to sell escalation as routine.

In this moment, after Venezuela and amid threats to Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico, “defending against the United States” is less a fantasy of matching firepower than an attempt to deny easy outcomes. It means making intervention politically expensive, strategically complicated, and morally radioactive. For a region that has spent two centuries learning how power speaks, the most realistic shield is not the one that stops the first strike. It is the one that makes the next strike harder to justify—at home, abroad, and in the history books.

Also Read: Venezuela Downfall Diaries: Maduro’s Last Drive Before New York Cell