Mexican Muralist Monroy Dies at One Hundred Two, Leaving Revolt

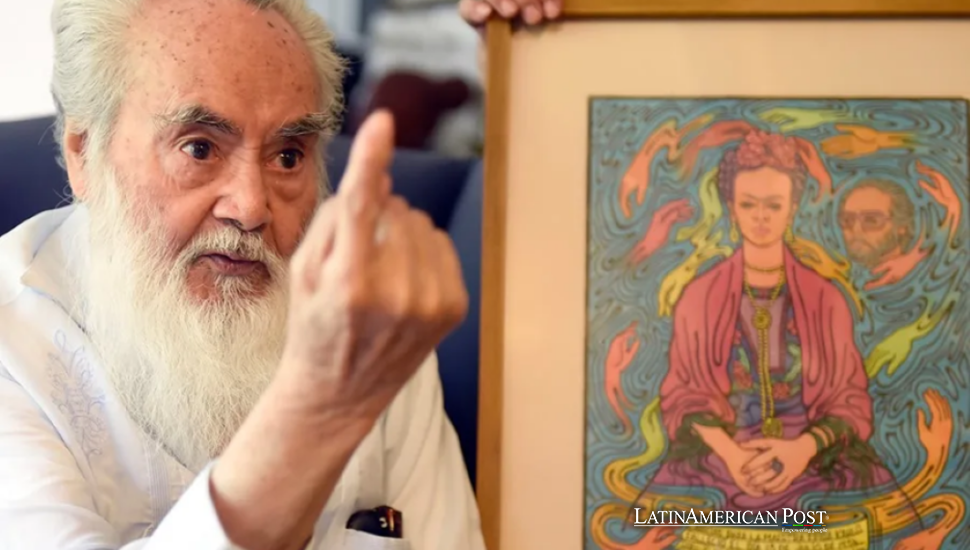

In Cuernavaca, the death of Guillermo Monroy Becerril closes a living link to Mexico's muralist century. A Frida Kahlo disciple and Rivera assistant, he kept insisting art was inseparable from social struggle, even as institutions honored him late.

The Last Apprenticeship, the Last Message

The micro scene is not a studio with wet paint or a scaffold high against a wall. It is a short public message posted after he died that tries to capture an entire life in a few lines. The Morelos state government announced the death of Guillermo Monroy Becerril at 102, calling him a great of art, an exceptional muralist, a disciple of Frida Kahlo and an assistant to Diego Rivera, a man whose life and work were tied to the pillars of Mexican art.

He died in Cuernavaca, the capital of the state where he lived, neighboring Mexico City. He had turned one hundred two on January seven. His age matters, not as trivia, but as a reminder that Mexican muralism is not only history in books and museum labels. For a long time, it was also a living apprenticeship, carried in memory, transmitted in classrooms, held in the hands of artists who knew the origin story firsthand.

Monroy belonged to a group known as Los Fridos, students of Frida Kahlo, and contributed through murals, drawings, and printmaking, shaping the evolution of Mexican art. Trained at La Esmeralda, his work reflects influences from Kahlo, Rivera, Peña, Anguiano, Lazo, Chávez Morado, and Ramírez, making him a key figure in the development of the muralist movement.

The trouble is that when a country loses a figure like this, it loses more than a person. It loses continuity. The gap is not only emotional. It is institutional. It forces a question about what Mexico wants from its public art tradition now, and what it is willing to fund, protect, and teach.

A grounded everyday observation sits underneath the official tribute. Most people pass murals the way they pass weather, half noticing, absorbing without naming. A wall becomes part of the commute. A school corridor becomes background noise. You look up only when something stops you. Monroy's career was built on the idea that walls are not neutral. They are arguments you live inside.

Art as Social Struggle, Not a Decorative Role

In September 2024, Mexico's government, through the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature, awarded Monroy the Gold Fine Arts Medal in Visual Arts, alongside sculptor Geles Cabrera and fellow artist Arturo Estrada. The award signals something important about how institutions see him. It places him, officially, among the figures who made the country's visual culture durable.

But the sharper part is what he said when receiving it. He described himself as a leftist fighter and emphasized that social struggle was an integral part of his identity, driven by a revolutionary and plastic sensitivity. He expressed that he could not paint without engaging in social struggle. He thanked those who influenced him and connected their impact to his fight for campesinos, Mexican workers, students, and all who strive for justice.

Those lines matter because they refuse the comfortable version of muralism as heritage wallpaper. In his telling, muralism is not a style. It is a stance. It is art that chooses sides and stays there, even when political winds shift, and institutions prefer softer language.

What this does is put pressure on how cultural policy frames art. An artist like Monroy fits neatly into national pride when he is described as a disciple of Kahlo and an assistant to Rivera. That is the museum-friendly framing, the lineage story, the prestige transfer. His own framing is harder. It demands that you see the campesino, the worker, and the student not as themes but as commitments.

The wager here is whether Mexico's cultural institutions want muralism as a mere brand or as a dynamic, political art form that continues to demand public accountability and relevance.

Where the Walls Still Speak

Monroy's work appeared in major Mexican venues, including the Palace of Fine Arts, the Gallery of Mexican Plastic Arts, the Anahuacalli Museum, and the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Studio House Museum. It also traveled internationally, shown in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Russia, China, and the United States. That geographic spread suggests a second life for Mexican muralism, not only as a national narrative but also as an exportable language, a way the world learned to read Mexico's twentieth century through images.

His public murals include Belisario Domínguez and Mexico 1847 at the Belisario Domínguez primary school in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, and El beneficio de las vías de comunicación en la tierra at the Secretariat of Infrastructure, Communications and Transport in Mexico City. These are not private canvases collected and stored. They are works placed in civic spaces, schools, government buildings, and along the routes where ordinary life happens.

That placement is the point. Muralism was built to be seen by people who do not buy art. It was built to teach and provoke in the open air of public life. It was also built in a Mexico shaped by revolution, agrarian struggle, labor organizing, and the long aftershocks of inequality. When Monroy says he could not paint without social struggle, he is not posing. He is placing himself inside the tradition's original job description.

His death, therefore, is more than a cultural obituary. It prompts reflection on what it means to keep public art accessible and alive. Who maintains murals in schools and government buildings? Who funds their conservation? Who supports new murals? Who trains future artists to understand the significance of these walls?

There is a temptation, when someone reaches 102, to wrap their story in admiration and close the file. Monroy's own words resist that closure. They insist on unfinished work. They insist on struggle.

And maybe that is the most human line a reporter can write about a muralist who lived this long. The wall outlasts the painter, but it still asks for something from the people walking past it.

Also Read: Chile Border Politics Harden as Kast Countdown Haunts Northern Highlands