Mexican Union Masks and Cartel Money Challenge Sheinbaum’s Midterm Fight

As Mexico nears Claudia Sheinbaum’s midpoint, cartel operatives are slipping into union shirts, turning extortion into paperwork. Arrests in La Laguna and Ecatepec show how CATEM fronts and local “protector” groups exploit businesses—and how the state tries to answer back.

Power Gathers While Crime Blends In

The year is closing with Mexico caught in a familiar race against the calendar: the government trying to prove it can govern, and organized crime trying to prove it can endure. Ahead of the midpoint of President Claudia Sheinbaum’s term, the executive branch is tightening its grip—through key changes at the Attorney General’s Office (FGR) and the institutional groundwork laid through the National Intelligence Center (CNI) and the Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) within the Ministry of Finance. In theory, that consolidation should translate into cleaner investigations, faster case-building, and fewer blind spots where money vanishes, and violence reappears.

In practice, the challenge is immense precisely because the enemy has changed uniforms. Today’s criminal operators do not always look like armed men posted on a highway. Increasingly, they look like paperwork: someone with a stamp, a badge, a union shirt, a “service” offered to small businesses that can’t afford to refuse. Cartels and gangs have grown more sophisticated in their disguises and protections, while also strengthening their connections to those in power. In that convergence—crime learning to speak institution, and institutions struggling to purge compromised tissue—citizens become the collateral: ranchers pressured to pay to move cattle, shopkeepers paying for “protection,” families watching the local economy convert into a tollbooth economy.

The most corrosive detail is the way legitimacy itself gets weaponized. When criminal organizations masquerade as unions or use legitimate organizations to exploit the legal economy, they do more than steal money. They steal the language ordinary people rely on to seek help—labor rights, representation, advocacy—until those words sound like threats. The result is precariousness that feels administrative rather than dramatic: fewer open confrontations, more quiet payments, more fear disguised as procedure.

El Limones and the Union Shirt That Opened Doors

That new criminal grammar was exposed in La Laguna, a region of northeastern Mexico, where the state’s recent operations suggest it is watching, listening, and attempting to dismantle networks alerted by citizens and local authorities. The most emblematic case is the arrest of Edgar N., alias “El Limones”—an alleged member of Los Cabrera, one of the Sinaloa Cartel’s branches in the area, who also held a position within the regional structure of CATEM, one of the country’s largest labor unions.

The scale of the response signaled the stakes. The Security Cabinet, headed by Omar García Harfuch, arrested five associates and froze several bank accounts linked to the network. Authorities say the group extorted ranchers and merchants, stole fuel, and laundered money for Los Cabrera—the kind of portfolio that turns a local racket into a cartel service provider. The federal government alleges that El Limones “received millions of dollars in deposits of unjustified origin,” transferred funds to companies tied to money laundering, and participated in buying and selling real estate, luxury vehicles, jewelry, watches, and gambling. What matters is not the luxury itself, but how it was supposedly purchased: by treating the union brand as a passkey into the legal economy.

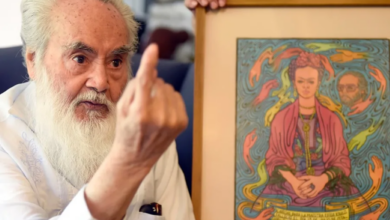

To carry it out, the alleged criminal wore CATEM’s shirt, both literally and figuratively. And CATEM is not a fringe structure. It is a union with millions of members, founded 15 years ago by Pedro Haces, a leading parliamentary figure within Morena. After the arrest, Haces posted a video attempting to distance himself from El Limones, separating union activity from extortionate plunder. But politics rarely moves at the speed of social media evidence. Photographs surfaced showing Pedro Haces alongside El Limones, and El Limones with union officials in La Laguna. Even the captioned image of Armando Cobián, Pedro Haces, and Edgar Rodríguez “El Limones” became its own grim metaphor: the proximity that denies itself.

For the government, this is the kind of operation that can’t be evaluated only by the arrest. It’s also a test of how aggressively the administration is willing to cut into the networks that connect crime to political power. The situation is not easy for Sheinbaum’s team, which is trying to eradicate the problem without fatally wounding one faction or another within Morena—a surgery of extreme complexity. Individuals like El Limones thrive because they can connect to power from multiple directions: the administration, the unions, and the local bosses who broker access. Every month that passes without verdicts deepens those connections and makes the network harder to unwind. The temptation to avoid intervention grows precisely because intervention risks exposing the wiring.

Ecatepec’s Mirror and the Slow Work of Conviction

The pattern is not confined to La Laguna. Over the last six months, another arrest has underscored how easily criminal unionism can manufacture legitimacy in the open. Authorities captured Alejandro Gilmare, alias “Choko,” a former ministerial police officer from the State of Mexico, who led an organization called La Chokiza. It presented itself as an informal union offering members legal advice, business advertising, protection against extortion, and other services. It was popular—popular enough that Azucena Cisneros, the Ecatepec mayor and a member of Morena, recorded a video with Gilmare celebrating the organization’s anniversary. Gilmare also had a romantic relationship with Sandra Cuevas, the former mayor of Cuauhtémoc in Mexico City—a reminder that social proximity can be as valuable as firepower.

Now, authorities accuse El Choko and associates of extortion, homicide, and property theft, along with other former members of the gang. His trajectory offers a bleak lesson: how quickly these figures can amass power, and how slowly—overwhelmed or negligent—the state can respond. In a country where extortion has become a growing national problem, the point of such arrests can’t merely be to announce action. It must be to build cases that survive courtrooms, to translate intelligence into convictions, and to prove that “protector” brands won’t be tolerated when they function as predatory governments.

Ecatepec offers yet another example in Guillermo Fragoso, a veteran of criminal unionism wanted for extortion and kidnapping, and described as La Chokiza’s rival. He moved through the Libertad union, then created others, including the Union of National Unions and Organizations (USON) and the March 25th Union. Like El Limones, he allegedly built a network of relationships beyond his municipality that allowed him to advance for years. His name even appears in an investigation involving Raúl Rocha, the owner of Miss Universe, and an alleged criminal network whose leaders, Jacobo Reyes and Jorge Alberts, describe Fragoso as a facilitator—someone who can lend “people,” introduce them to mayors, and help move weapons.

This is the real frontier Mexico is facing: crime that not only fights the state, but inhabits it—at local, state, and federal levels—using legitimacy as camouflage. In that landscape, arrests are the first stitch, not the cure. Trial and conviction are the only ways to suture the wounds and begin healing a battered state, because they test whether power is willing to prosecute the very disguises it has historically depended on. The work is slow, painful, and politically risky. But the alternative is worse: a country where union shirts become uniforms for predation, and where the legal economy becomes just another territory to be conquered.

Also Read: Colombia Gulf Clan Gets Terrorist Tag as Fentanyl Fever Rises