The Latin American Presidents Who Faced U.S. Courts As Sovereignty Meets Handcuffs

The U.S. states it will try Nicolás Maduro after his Saturday capture in Caracas, continuing a pattern of leaders who were previously beyond prosecution now appearing in court. From Panama to Honduras, these cases intersect justice, geopolitics, and regional memory.

Maduro’s Indictment Joins a Long, Uneasy Lineage

When Washington announces it will prosecute a sitting Latin American leader, the information rapidly circulates, generating questions: Is this accountability, an extension of influence, or both?

This time, the name is Nicolás Maduro, the Venezuelan president captured in Caracas on Saturday, according to the text. The United States says it will put him on trial. U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi pointed to an indictment dating back to 2020. She charged Maduro with four counts, including conspiracy to commit narco-terrorism. The filing also includes Cilia Flores, Venezuela’s first lady, who was captured alongside him in the special operation.

In regional memory, the combination of capture, indictment, and extradition is associated with prior instances in which U.S. courts and authorities extended their reach into Latin American jurisdictions. The individuals cited include Manuel Antonio Noriega of Panama, Alfonso Portillo of Guatemala, and Juan Orlando Hernández of Honduras. These cases each present different charges and contexts, but a similar image: a former or current head of state appearing in a foreign court.

Noriega And the Invasion That Set the Template

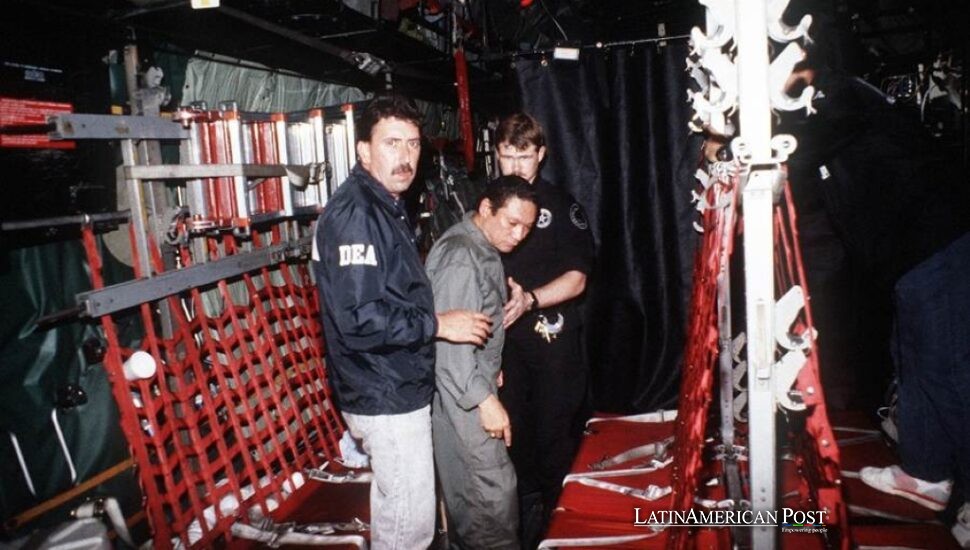

The case that still feels like the prototype is Manuel Antonio Noriega, the strongman of Panama and de facto leader from 1983 to 1989. He rose to power as head of the Panamanian Defense Forces. The text describes what many Panamanians remember as a period marked by censorship, political repression, and allegations of corruption. Noriega maintained an ambiguous relationship with the United States. He collaborated with intelligence agencies even as he consolidated authoritarian control.

By the late 1980s, U.S. courts accused Noriega of drug trafficking and money laundering. The relationship collapsed. In 1989, the United States launched the invasion of Panama known as Operation Just Cause. It culminated in Noriega’s capture in 1990. He was tried and convicted in the United States. Later, he faced legal processes in France and Panama.

For Latin America, Noriega’s case concerns not only criminal charges but also the transformation of a geopolitical relationship into a legal matter. A former collaborator becomes a defendant. The legal record is established, alongside perspectives that question the intersection of law and strategy.

Portillo, Hernández, And the Courtroom as Afterlife

The text then jumps to a different kind of downfall: corruption rather than invasion. Alfonso Portillo, president of Guatemala from 2000 to 2004, left office under a cloud of scandals. Afterward, he was accused of embezzling millions of public funds, including diverting funds from the Ministry of Defense. In 2008, he was extradited to Mexico on various charges and later to the United States, where he faced trial for money laundering tied to funds stolen from the Guatemalan state. Six years later, in a federal court in New York, he pleaded guilty and went to prison, later returning to Guatemala after serving his sentence.

If Noriega’s case was about the blunt force of military power, Portillo’s illustrates the bureaucratic afterlife of governance: bank transfers, laundering routes, quiet extraditions. It is still sovereignty punctured, but through paperwork rather than tanks.

Then comes Juan Orlando Hernández, president of Honduras from 2014 to 2022, whose case, according to the text, was built around accusations of conspiring to traffic drugs, possessing weapons, and maintaining ties to criminal organizations. Investigators alleged he took massive bribes and used state security forces to facilitate cocaine shipments to the United States. In 2022, he was arrested in Honduras and extradited. In 2024, a federal court in New York found him guilty of narcotics and weapons-related charges and sentenced him to 45 years in prison. The text adds a twist that would feel surreal in any courtroom drama: in December of the previous year, he was pardoned by President Donald Trump.

Impunity As Excuse or Explanation

In Latin America, where impunity often feels like a permanent state of affairs, the idea that a U.S. conviction can be undone by a U.S. political decision is not just irony; it is confirmation of the region’s deepest cynicism. The courtroom can look like moral clarity, until it looks like leverage again.

Extending the thread of U.S. legal influence in Honduras, the text adds another name: Rafael Leonardo Callejas, who served as president from 1990 to 1994. The text says he was processed in the United States after turning himself in over soccer corruption linked to FIFA. Due to fragile health, a New York court sentenced him in 2020 to time served, counting his pretrial detention.

The details matter because they show how wide the net can stretch: from alleged narco-conspiracies to the global economy of sports bribery, the U.S. courthouse becomes a stage where Latin American elites can be disciplined for different sins, sometimes real, sometimes entangled with power.

Finally, the text widens beyond U.S.-based prosecutions to extradition battles. Alejandro Toledo, president of Peru from 2001 to 2006, fought in the United States to avoid extradition to Peru over bribery allegations, particularly involving the Brazilian firm Odebrecht. In 2023, the U.S. approved his extradition. A year later, he was sentenced to 20 years and 6 months for accepting Odebrecht bribes, and in September 2025, he received a second sentence of 13 years and 4 months for money laundering. The text notes the sentences are concurrent, meaning his effective prison time is a bit more than two decades.

These cases collectively illustrate a recent trend in Latin American governance: presidencies that may end with legal proceedings, extradition, or incarceration rather than retirement.

Now, Maduro is being inserted into that map, charged since 2020, captured in 2026, and paired legally with Cilia Flores. What happens next will be argued in courts and capitals, but the emotional response across the region is already visible: the uneasy recognition that sovereignty is not only defended by flags. It is also tested in the places where handcuffs click, where prosecutors speak, and where Latin America’s long history with Washington gets rewritten, case by case, into the language of law.

Also Read: Venezuelan Tren de Aragua and Cartels Collide with U.S. Crackdown