Ecuador’s Democracy on Edge as Anger and Austerity Collide

When Ecuador’s young president, Daniel Noboa, set out for a quiet rural town this week, he expected a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Instead, he left under attack. By the time his convoy sped out of El Tambo, its windows were cracked, protesters arrested, and the air thick with tear gas — a moment that captured a nation’s growing unease, where austerity, inequality, and distrust have turned even the simplest journey into a potential showdown.

A President Under Fire — or Under Pressure

It began as a protest. Locals had blocked the road, furious over Noboa’s decision to eliminate a long-standing diesel subsidy that had kept food and transport prices stable for decades. When his black Suburban tried to push through, rocks rained down. Hours later, government spokespeople claimed someone had opened fire, describing the incident as an “assassination attempt.” Prosecutors charged five people with attempted homicide. Whether bullets or stones hit the vehicle remains under investigation.

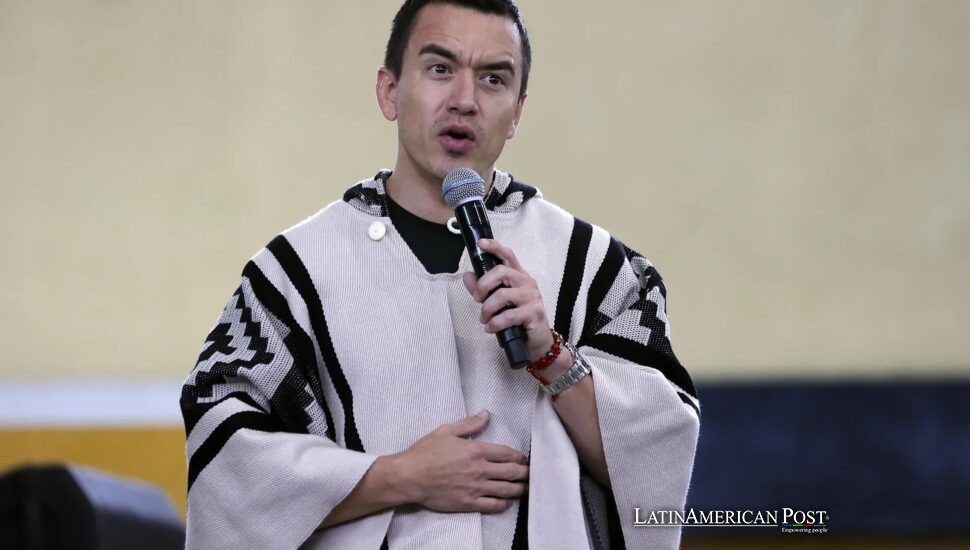

To Noboa’s administration, this was more than a riot. It was an attack on democracy itself. “We will continue working without fear,” the 36-year-old president said afterward, his tone defiant. His interior minister, John Reimberg, blamed the violence on “a deliberate effort to destabilize the country.”

But in Ecuador’s Indigenous heartlands, the story sounds different. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), the nation’s most powerful social movement, dismissed the “assassination attempt” as political theater — a convenient excuse, they said, to justify repression. “This is a provocation designed to criminalize protest and distract from Ecuador’s social crisis,” their statement read.

That crisis is real. The country’s streets hum with discontent, and Noboa’s image — a billionaire’s son turned reformist outsider — is colliding with the everyday exhaustion of those he governs. The cracked glass of his convoy has become a metaphor: a young president’s polished optimism meeting the jagged edges of a weary nation.

Austerity Meets Exhaustion

At the center of Ecuador’s turmoil is one of Latin America’s most combustible issues: fuel subsidies. For generations, cheap diesel has been a political pressure valve, cushioning the poor from inflation and giving small farmers a fighting chance. Noboa argues it’s an unsustainable drain — a subsidy that benefits smugglers and upper-class drivers more than the people it’s meant to help. Scrapping it, he insists, will save hundreds of millions of dollars, money he promises to reinvest in schools and hospitals.

But promises don’t fill gas tanks. In Ecuador, fuel prices are emotional, not just economic. When past leaders have tried to touch them, the country has exploded — most famously in 2019, when then-President Lenín Moreno fled Quito amid Indigenous-led uprisings that paralyzed the nation. Those memories still burn.

Now, Noboa faces the same fire. Protests have spread from the highlands to the coast. Roadblocks cut off food and fuel. Truckers idle in frustration, farmers can’t move their harvests, and supermarkets in Quito are seeing shelves thin again. The government has declared states of emergency in multiple provinces, giving soldiers wide latitude to control unrest.

For many Ecuadorians, the subsidy fight is a symptom, not the disease. Prices rise, wages stagnate, and crime spirals while politicians preach fiscal discipline. Noboa’s technocratic promise — that austerity today will buy prosperity tomorrow — rings hollow in communities where tomorrow has stopped arriving.

Indigenous Power and Populist Politics

The confrontation has revived an old fault line: the struggle between Ecuador’s urban elites and its Indigenous movements. Groups like CONAIE see the protests as part of a longer fight against exclusion. “We are not terrorists. We are the ones defending life,” an Indigenous leader told reporters outside Quito.

Noboa’s decision to frame the El Tambo attack as an assassination attempt deepened that divide. To his allies, it proved the president’s bravery in the face of chaos. To his critics, it revealed how quickly a government will militarize language to paint dissent as threat.

The contrast is jarring: a young, U.S.-educated president — heir to Ecuador’s largest banana empire — describing himself as a reformer besieged by “vandals,” while Indigenous families block roads because their children can no longer afford bus fares. The imagery is potent: armored cars versus handmade signs; soldiers in fatigues facing farmers in straw hats.

Noboa presents himself as pragmatic, centrist, modern — the man who can rescue Ecuador from political decay and gang violence. But to the country’s marginalized majority, his austerity rhetoric sounds like déjà vu: another generation of elites preaching sacrifice from behind tinted glass. His close alignment with Washington, his embrace of Trump-era security cooperation, and his vow to “restore investor confidence” have reassured foreign capitals. At home, they reinforce an old suspicion — that every reform seems to ask the poor to pay first.

The Fragile Road Ahead

Whether what happened in El Tambo was an assassination attempt, an accident, or an explosion of anger, one truth remains: Ecuador is brittle. Noboa’s calls for “law and order” may play well with business leaders, but they risk alienating the same rural and Indigenous communities whose cooperation he desperately needs.

The nation’s experiment with militarized governance has not quelled its gang crisis, nor has its austerity agenda revived the economy. Instead, Ecuador feels trapped between fear and fatigue. Each protest, each decree, each roadblock feels like a referendum on faith — not just in Noboa, but in democracy itself.

If the president wants to survive this storm, he must stop mistaking dissent for danger. His challenge is not to silence the anger but to listen to it — to turn confrontation into dialogue before distrust hardens into rebellion. Ecuador’s Indigenous movements have often acted as moral anchors, forcing governments to confront inequality. To dismiss them now would be not only unjust but self-defeating.

When Noboa’s convoy entered El Tambo, he may have seen a mob. But behind those stones were citizens — people who once believed a young president might bridge the country’s divides. Instead, they saw him roll past behind bulletproof glass.

Also Read: Mexico’s Red-Pill Reckoning: How One Campus Murder Exposed a National Crisis

Whether he chooses to roll down that window — literally and politically — will determine more than his presidency. It will decide whether Ecuador’s democracy, cracked but not yet shattered, can still hold.