Guatemala Waits, Planes Idle, and Children Linger in a Legal and Political Crossfire

A judge’s last-minute order grounded U.S. deportation flights and forced a pause in an urgent, disputed campaign to send unaccompanied Guatemalan children home. Behind the halted buses and frozen manifests are families waiting by the door—and children caught between two governments, two stories, and two weeks of legal limbo.

A midnight rush, a sudden silence

It started just before dawn.

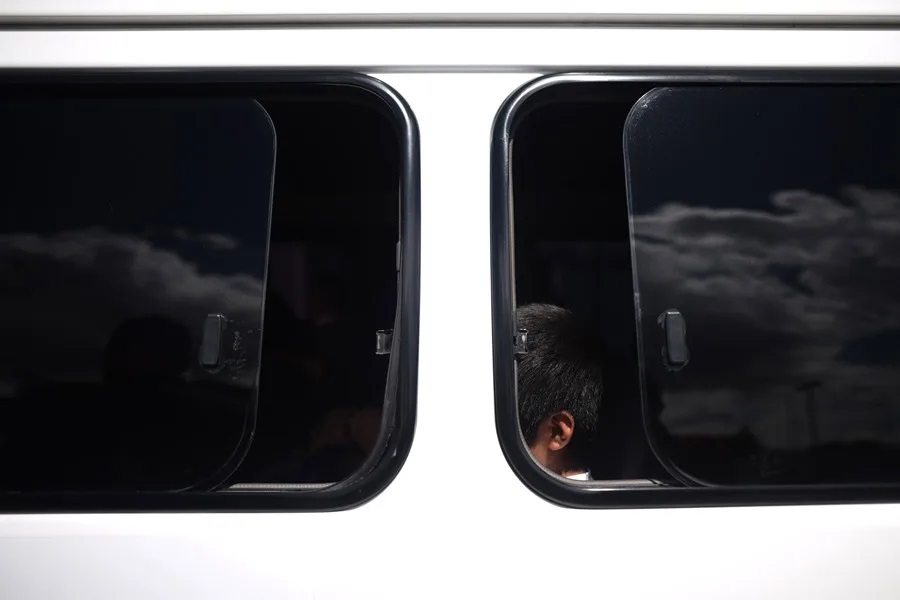

Immigration attorneys scrambled into federal court as rumors swirled that dozens—maybe hundreds—of unaccompanied minors were about to be flown out of the United States before lawyers could even reach the airport. In the quiet chaos of a holiday weekend, unmarked buses rolled up near airstrips. Some children reportedly received only minutes’ notice. At least one teen, according to his mother in Guatemala, called at 1 A.M. from Texas to say he was being put on a plane.

But by midday Sunday, a federal judge had issued a temporary restraining order. The children—some as young as 10, some with pending asylum cases, some unsure what was happening at all—would not be leaving just yet.

The first order covered ten named children. By the afternoon, the judge expanded it to protect all similarly situated minors. The message was immediate: if children are being deported, the courts—not a policy memo or a pilot program—will determine whether and when they go.

The judge asked government attorneys directly: had any planes left? The answer, delivered by a senior official, was vague but telling. If an aircraft had departed, it had since returned. The flights were grounded. The system, for a moment, had blinked.

What’s in a word: “repatriation” or “deportation”?

To the White House and Guatemala’s president, the flights were reunifications. Nothing more. Children returning to families they missed, in a program framed as humane and mutually agreed upon.

To attorneys and immigrant advocates, the truth was more complicated—and possibly unlawful. Several of the children had active cases pending before immigration judges. Others had expressed credible fear of returning to Guatemala. Many, their lawyers argued, had not asked to be sent back at all.

What you call the flights matters. “Repatriation” sounds voluntary, restorative. “Deportation” implies force, and triggers legal protections—especially for children under 18 who arrived without parents or guardians. The difference could shape years of precedent.

And it’s not academic. Guatemala’s government had lined up to receive the children. At a reception center in Guatemala City, parents waited, paperwork in hand. But the buses never came. Neither did the planes. As reports broke across outlets like Prensa Libre and the BBC, confusion set in. Some families were heartbroken. Others were relieved.

“We don’t know when he’ll return,” one mother told local reporters, speaking of her 17-year-old son who had been preparing to board a flight in Texas.

Fear in both directions

One uncle traveled from his rural village to the capital, expecting to meet his nephew at the reception center. Instead, he stood outside and described why the boy had fled in the first place.

“Because we’re poor. And there’s no cure here.”

That bleak phrase—a mix of economic hardship and inadequate health care—captures a more profound truth. Children don’t migrate alone unless something’s broken. For some, it’s gang threats. For others, it’s hunger, untreated illness, or abuse. In court, advocates insisted that at least some of the minors faced credible risks if returned to Guatemala and that deporting them without an opportunity to make their case would violate federal law.

Back in Texas, families and attorneys worked overtime to figure out who was on which list, who had what protection, and whether anyone had slipped through. For now, the order holds. But it expires in 14 days.

The pause may be temporary. The stakes are not.

EFE/Esteban Biba

A legal test, a political flashpoint

The halted flights now hang like a test balloon over broader immigration policy.

In the U.S., President Trump’s second term has brought a series of hardline enforcement efforts: mass deportation promises, expanded removals, and policies designed to deter migration at any cost. Supporters say they restore order. Critics argue they shortcut due process—especially for children.

In June, the Supreme Court allowed the administration to resume deporting migrants to countries other than their homeland without first hearing out their safety concerns. That decision stoked fears that minors, too, could be removed without complete screenings.

Stephen Miller, a key White House adviser, called the court’s injunction “a disgrace,” saying the judge was blocking children from “reuniting with their families.” But the court wasn’t ruling on where the children should go. It was ruling on how.

Do unaccompanied minors—some of whom have legitimate asylum claims, others who arrived in confusion or fear—have a legal right to a hearing before being deported? For now, the answer is yes.

And what about Guatemala? President Bernardo Arévalo has been a willing partner, promoting the pilot program as a humanitarian path to reunite families. But even he admitted, in remarks echoed across Guatemalan media, that “not every case is the same.”

He’s right. “Home” for one child may be a parent’s open arms. For another, it may be a street with a price on its head, or a house that no longer feels safe. The judge’s order doesn’t bar returns. It says they can’t happen unthinkingly.

Two weeks. That’s what the court gave everyone.

Time to sort the files, verify the stories, and decide whether these flights are repatriations or shortcuts. Whether these children are going home or being sent away from one.

The planes remain grounded. The court is watching. So are the parents.

Also Read: Colombia’s Peace Needs Stricter Juvenile Laws for Heinous Crimes

And the children, many already in custody, are waiting—between a runway and a courtroom, a promise and a procedure, a country they left and one that must now decide whether to let them go.