Brazil Debates Defunding Funk Music That ‘Glorifies Crime’

A push by São Paulo city councilors to cancel government contracts for performers accused of praising drug gangs has spread across Brazil, reviving a familiar question: where does cultural storytelling end and criminal advocacy begin in the favelas’ signature sound, funk?

From One Council Motion to a Nationwide Crusade

It began with a single clause in a modest draft ordinance—barely a ripple in São Paulo’s municipal paperwork. Within weeks, it triggered a political storm sweeping through more than 150 Brazilian cities.

When first-term councilor Amanda Vettorazzo proposed that artists funded with public money must explicitly vow not to promote organized crime, she imagined a simple accountability measure. “The bill is genre-neutral,” she told EFE. “But in Brazil, the artists singing that content are funk.”

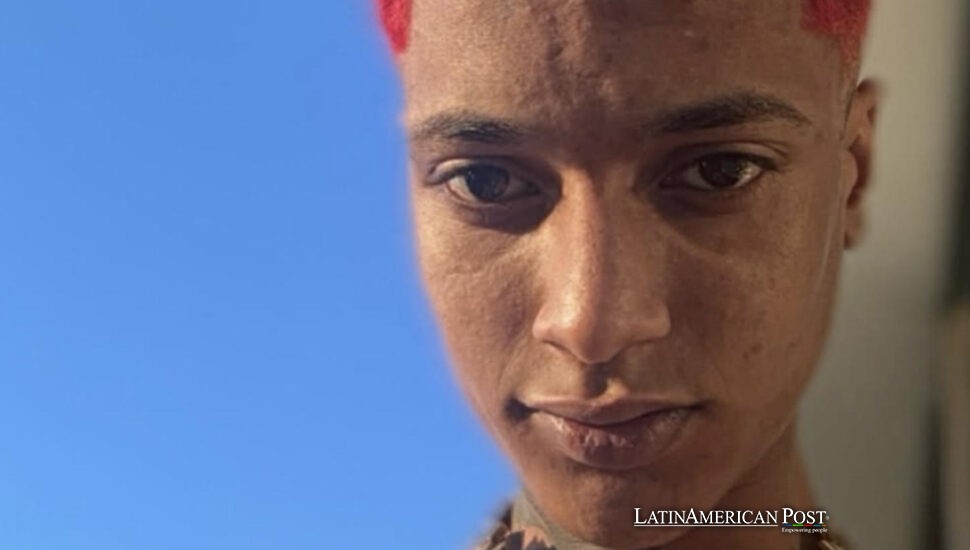

Supporters wasted no time giving it a name: the anti-Oruam law. Its namesake, Oruam—born Mauro Davi dos Santos Nepomuceno—is one of Rio’s fastest-rising funk stars and the son of the infamous Red Command trafficker Marcinho VP. In his lyrics, the younger Nepomuceno doesn’t hide his lineage; he embraces it. To fans, his verses are raw autobiographies. To critics, they’re a recruitment ad.

Within a month, identical proposals surfaced in Congress, state assemblies, and a dozen capital cities. What had begun as a local regulation was morphing into a nationwide test of artistic boundaries, state power, and class prejudice.

Funk’s DNA: Testimony or Temptation?

Funk was born in the baile parties of 1990s Rio—shaped by Miami bass and the daily textures of favela life: police raids, quick deaths, stolen luxury, fleeting joy. For many in Brazil’s peripheries, funk wasn’t entertainment. It was news.

And then came proibidão—funk’s darker, more explicit cousin. These tracks don’t just nod at violence. They name names. Drug bosses. Guns. Territories. Critics say it’s gone too far. “Kids see the best cars, the best chains, the prettiest women,” Vettorazzo argues, “and they think trafficking is the correct path.”

But Funk’s defenders see it differently. Thiago de Souza, a musicologist who’s spent years tracing funk’s evolution, offers a sharp counterpoint:

“You hear the word ‘death’ all the time. That isn’t a celebration. That’s a warning.”

To ban these lyrics, he argues, is to confuse diagnosis with endorsement. Juliana Bragança, a historian, agrees:

“What you hear in funk are narratives. Removing that mirror doesn’t remove the violence it reflects.”

Studies from the Federal University of Rio back her up: no statistical link exists between funk lyrics and homicide rates in the neighborhoods where the music is most played.

Still, proibidão remains polarizing and profitable. The media often paints it as the soundtrack of urban decay. On the streets, it’s something closer to the gospel: sacred, dangerous, and true.

IN@oruam

Culture Wars in a Country of Contradictions

This isn’t Brazil’s first attempt to police music born in the margins.

A century ago, samba dancers were hauled off to jail. Capoeira, the martial dance of Afro-Brazilian resistance, was criminalized for decades. Each time, the rhythms survived—later, they were canonized as national treasures.

That pattern isn’t lost on today’s artists. “The favela is always the scapegoat for social problems,” says de Souza. And funk, like samba before it, now stands trial in the court of public morality.

The loudest critics come from the evangelical right, whose influence in Congress has grown rapidly. Their core voters demand tougher crime policy. With its bullets and basslines, Funk makes an irresistible target that allows politicians to strike a blow against crime while avoiding more challenging questions about underfunded schools and abandoned youth.

But funk’s defenders say the crackdown reeks of selective censorship. They point to sertanejo universitário, Brazil’s wildly popular country-pop genre. Its biggest stars sing—often with state subsidies—about binge drinking, domestic spats, and party excess. No one calls for their defunding, nor are rock bands penalized for romanticizing cocaine.

Under São Paulo’s proposal, artists must sign a clause swearing not to glorify drugs or crime. Violation could result in fines and the repayment of public fees. But civil-liberties lawyers warn the language is dangerously vague. Could a song describing police brutality be deemed criminal advocacy? Could a lyric about carrying a weapon—whether condemning or contextualizing it—trigger a penalty?

These are not abstract questions. They are dilemmas tangled in Brazil’s deep race, class, and geography divides.

Platforms, Pathways, and the Politics of a Microphone

Even if the bill passes, its reach may be limited. The internet doesn’t check government contracts.

Oruam has more than 11 million monthly listeners on Spotify. He’s graced the cover of Britain’s Dazed magazine. His beats bounce from São João de Meriti to South London, from Rocinha to Berlin. Banning him from a city stage won’t pull him from playlists.

But a municipal contract can be the first rung out of poverty for young MCs without Oruam’s reach—those still performing on public stages, university festivals, or local radio. “Removing that platform,” Bragança warns, “narrows the routes out of the very narco economy lawmakers claim to fight.”

Behind every headlining MC are dozens more: baile funk sound engineers, dancers, food vendors, and lighting techs. Public gigs feed local economies that rarely receive government aid in any other form.

The Lula administration has so far stayed quiet. Sources close to the Cultural Ministry say officials fear re-igniting old tensions. In the 2010s, the Workers’ Party embraced funk as a tool of social inclusion. But the backlash was fierce. Today, with Lula trying to keep a fragile centrist coalition intact, few want to reopen that front.

Still, insiders hint that if a federal ban emerges, Lula’s team may seek a workaround: retooling federal arts grants to shield artistic expression, much as theatre groups were protected under the dictatorship.

For now, the bill is in São Paulo’s city council. Centrist councilors hold the swing votes. The final text may be softened, but the fire has already spread.

On Instagram, Oruam offered a parting shot:

“My music is the news you pretend not to watch.”

The basslines roll on—through tin-roofed alleys, Bluetooth speakers, and cars stuck in traffic. For some, they’re the sound of moral decay. For others, they’re testimony. For many more, they’re a paycheck, a dream, or just the loudest thing they’ve ever held in their hands.

Also Read: Uruguay Dances Until Dawn as Quevedo’s ‘Buenas Noches’ Lights Montevideo

The question Brazil must now answer is this: Can a nation this unequal punish lyrical violence without criminalizing people with low incomes who speak it?

The stage is set. The speakers are on. And the country, once again, is listening. Not all of it likes what it hears.