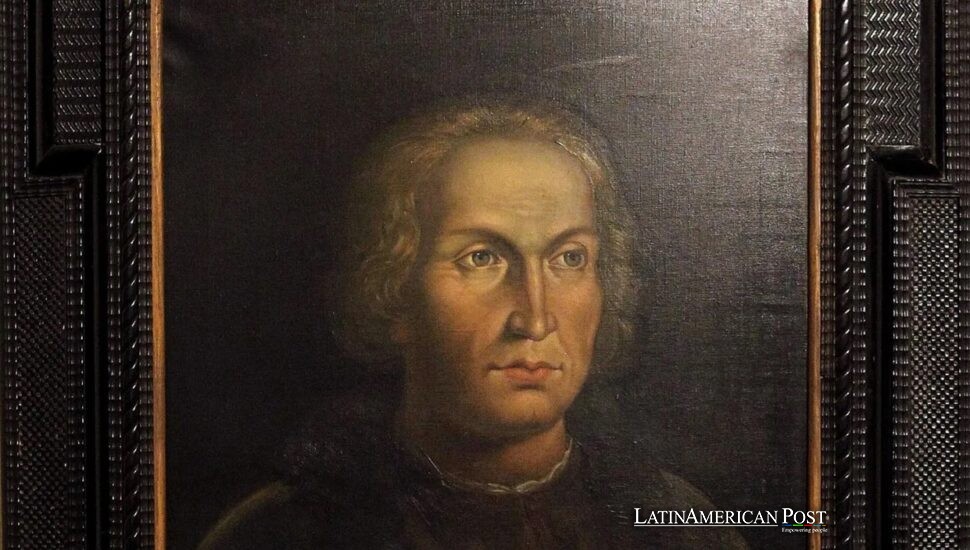

Columbus Without the Myths: A Stubborn Genius Who Miscalculated the World

Five centuries later, Christopher Columbus remains less a man than a mirror, reflecting the stories nations tell about themselves. A new biography dismantles those legends with documents and nuance, recasting the explorer not as a villain or a saint, but as something far more interesting—a stubborn, calculating, and complicated human being.

The Genoese, Not the Man of a Thousand Birthplaces

Few figures have inspired as much patriotic wish-casting as Columbus. For centuries, he’s been claimed by a dozen countries—Spain, Portugal, France, even Greece and Switzerland—all eager to pin his legacy to their flag. Historian Esteban Mira Caballos, in his sweeping new biography, has little patience for such myths. “The evidence is overwhelming,” he told El País. “Columbus was Genoese.“

That conclusion might sound simple, but it cuts through centuries of speculation, pride, and myth-making. Columbus himself invited confusion, blurring his origins in letters and documents to appear more cosmopolitan, more mysterious, and perhaps less provincial than he really was. Mira Caballos argues that before we can debate what Columbus meant to history, we must first understand who he was—a merchant mariner from the bustling port of Genoa, molded by trade winds and account books, not divine destiny.

That grounding matters. Genoa produced shrewd sailors, gifted mapmakers, and hard-nosed businesspeople who trafficked in both goods and ideas. Columbus’s genius wasn’t celestial inspiration—it was persistence. He sold a dream to Europe’s most skeptical monarchs and then made it real through sheer obstinacy.

A Convert’s Faith—and the Politics of Persuasion

If his birthplace has been contested, so has his faith. Was Columbus secretly Jewish, a crypto-believer sailing under Christian disguise? Mira Caballos dismantles that romance, too. “He was not Jewish,” the historian said. “He was a converso—a convert—whose public piety was essential to winning royal support.“

Columbus understood the politics of faith in an era when conversion could save or destroy one’s life. He prayed publicly, cultivated the Virgin Mary’s protection, and flattered the Catholic Monarchs with visions of divine purpose. To Queen Isabella, he even declared that Jews and converts were enemies of Christian prosperity—a statement both strategic and chilling.

Yet, beneath that orthodoxy, something stranger churned. Columbus scribbled biblical prophecies in the margins of his books and dreamt of retaking Jerusalem with the wealth he hoped to find across the sea. He was part zealot, part opportunist—a man whose spiritual certainty could justify any voyage, any cost.

“He was a convert who practiced Christianity with fervor but kept certain Jewish convictions,” Mira Caballos told El País. That contradiction, he argues, was the secret engine of Columbus’s ambition. His faith wasn’t stable—it was combustible. And it fueled the gamble that changed the world.

The Most Fruitful Mistake in the History of Maps

As a sailor, Columbus was gifted. As a scientist, he was hopelessly wrong. His westward route to Asia—the dream that made him famous—was built on bad math and wishful thinking. To solve the era’s central problem—the vast, unbridgeable distance between Europe and Asia—he reduced the planet’s circumference by about a quarter, using dubious medieval authorities like Pierre d’Ailly and Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli to support his case.

It was, in Mira Caballos’s phrase, “the most fruitful mistake in history.“

Portugal’s experts laughed him out of the room; Spain’s initially did the same. What convinced the Crown wasn’t the calculation but the conviction. Columbus wrapped geography in theology, transforming a business pitch into prophecy. He promised not just gold but revelation, casting his expedition as part of God’s unfolding plan.

The result was a shoestring voyage—three small ships, barely seaworthy, led by a man who believed divine providence would make up for faulty charts. He returned with gold trinkets, exotic birds, and people adorned with feathers, who would be paraded like miracles. It wasn’t evidence of Asia, but it was a spectacle. The Crown bought it, and a second expedition followed, this time an armada.

Columbus had discovered the art of selling discovery itself: in politics, what you bring home matters more than how you got there.

A Skilled Navigator, a Terrible Governor—and a Man Who Did Not Die Poor

The myths unravel faster once he steps off the deck. Columbus could read the ocean’s moods, but he could not govern men. His rule in the Caribbean was marked by a mix of cruelty and incompetence, sparking mutiny after mutiny. On his third voyage, he returned to Spain in chains—freed soon after but stripped of his titles forever.

From this fall, another legend was born: that Columbus died impoverished and forgotten. The truth, Mira Caballos insists, is less tragic. “The Crown paid him 8,000 gold pesos in 1504 and again in 1505,” he told El País. His descendants lived comfortably; his name never faded.

Nor was he entirely fooled about what he had found. While he continued to insist he’d reached Asia—pride and contracts demanded it—his private writings suggest he sensed something larger: a “new world” beyond any map. He couldn’t quite admit it aloud. He had promised the Indies, and to confess error was to invite ruin.

That, perhaps, is Columbus’s most actual constant: pride tethered to persistence. He was not the visionary who reimagined the cosmos; he was the relentless negotiator who bent facts until they yielded profit and faith until it served the empire. He made his mismeasurements sound like miracles—and Europe rewarded him for it.

In Mira Caballos’s telling, Columbus becomes neither an idol nor a villain, but a mirror for his time: a product of Genoa’s counting houses and the Reconquista’s militant Christianity, a skilled mariner and a mystic who quoted Scripture as a maritime policy. He embodied a Europe that sanctified conquest while preaching salvation, that celebrated discovery while erasing those it “discovered.”

And yet, he remains strangely modern. His mixture of audacity, self-promotion, and data manipulation would be familiar in any century. He changed the world not because he was right, but because he refused to admit he was wrong.

As Mira Caballos told El País, “Columbus was brave, blinkered, and brilliant in a dangerous way. He bent reality until it conformed to his conviction—and that’s how history works: the stubborn sometimes shape the map.“

The lesson, five centuries later, is not to romanticize him but to read him clearly—to trade myth for evidence, certainty for complexity. Columbus did not die a pauper. He did not spring from a thousand birthplaces. He didn’t steal a secret map. He made the greatest navigational blunder in history—and turned it into an empire.

Also Read: Mexico Turns ‘The Smashing Machine’ into a Story About Heart, Not Hype

That, Mira Caballos reminds us, is what makes him human: a genius of error, a man who mismeasured the world and found, by accident, another one.