Bad Bunny at Yale: How a Puerto Rican Superstar Became a Lesson in Identity

At Yale, a sold-out seminar dissects Bad Bunny’s latest album to explore Puerto Rico’s politics, rhythms, and diaspora. Professor Albert Laguna argues that universities must study the present, and students agree, as a Super Bowl debate over a Spanish-only performance raises the stakes.

A Pop Syllabus for a Puerto Rican Present

On a gray New Haven morning, the sound of plena drums spills from a Yale classroom window. Inside, students lean over laptops and lyrics sheets while Professor Albert Laguna taps the rhythm on his desk. The course, titled Bad Bunny and the Sound of the Contemporary Caribbean, filled within hours.

“Part of a university’s job is to understand the present moment,” Laguna told EFE. “And the present moment is Bad Bunny.”

Laguna, who has taught Caribbean history and culture at Yale since 2012, calls the class a study in musical aesthetics and politics, how a pop album can become a text about colonial legacies, corruption, migration, and belonging. This semester’s case study is “Debí tirar más fotos” (DtMF), the Puerto Rican star’s introspective, defiant 2024 record.

“You don’t have to like Bad Bunny to understand he’s important,” Laguna said to EFE, pushing back against critics who confuse personal taste with academic value. That stance feels especially pointed as conservative voices in the U.S. fume over Bad Bunny’s planned Spanish-only Super Bowl halftime show. For Laguna, the backlash only underscores the point: “The most streamed voice in the world is Puerto Rican and Spanish-speaking. That reality demands analysis.”

Rhythms That Remember, Beats That Argue

Each week, students unpack one track from DtMF. The room hums with discussion: bomba, plena, reggaetón, salsa. “We take one song and dissect it,” Laguna told EFE. The conversation stretches from the island’s African-rooted rhythms to its post-hurricane politics.

Bomba and plena, born from Afro-Puerto Rican resistance, were once neighborhood newspapers in song, records of survival and satire. To weave them into global pop, Laguna argues, is to insist the island’s history cannot be muted. “The rhythms he uses are archives,” he said to EFE.

For students, that method transforms listening into reading. Lyrics become case studies; beats become arguments. A sly rhyme about gentrification opens a debate about displacement in San Juan. A hook referencing migration turns into a discussion about Puerto Rico’s fiscal control board and the politics of austerity.

“In my four years here, I’ve never seen a class like this,” said Samantha Yera, one of the students quoted by EFE, her notebook littered with annotations from “Lo que le pasó a Hawaii.” Michaell Santos, another student, grinned: “I’m a superfan, I love his music, so what better way to learn than through something that speaks my language?”

Others bring different stakes. Daniel Torres, who plans to study medicine in Puerto Rico, told EFE that the class has shaped his view of his future patients. “It felt like a good way to understand the culture and the challenges before I go back,” he said.

By the time the playlist loops back to the album’s closing track, the class has covered everything from gender politics to colonialism, from protest anthems to trap love songs. The mood is equal parts seminar and studio session, serious thought with swagger.

A Diverse Classroom Speaking Spanglish to a Global Moment

Around the seminar table, Spanish and English overlap like harmony. Some students grew up between Bayamón and the Bronx; others learned their first Spanish in a Yale dorm. A few are monolingual English speakers deciphering slang one lyric at a time.

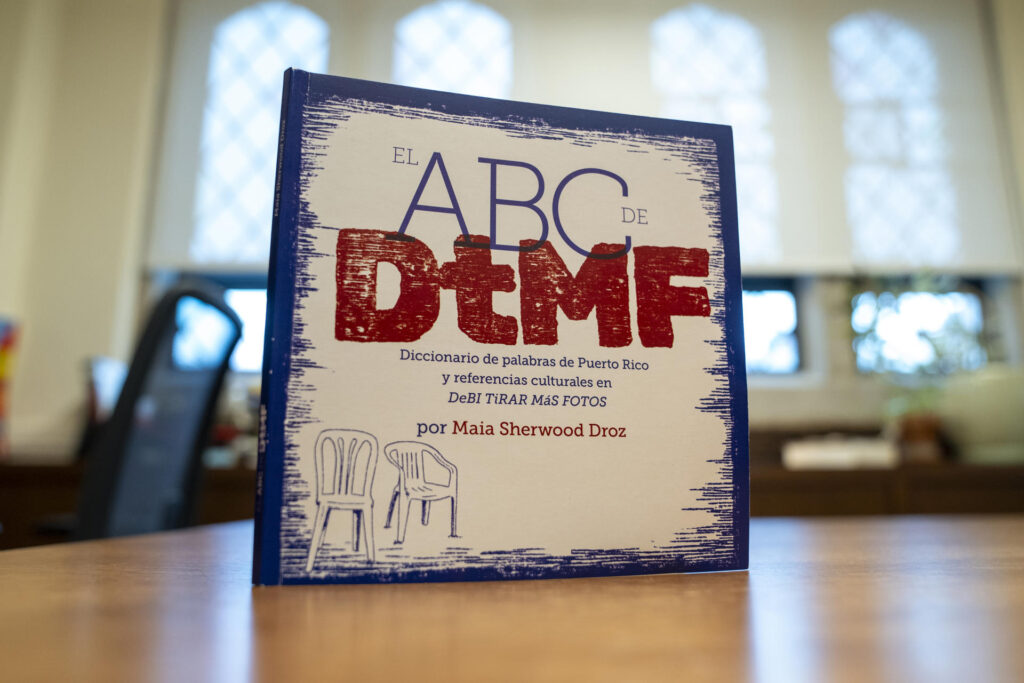

Laguna embraces the mix. He credits linguist Maia Sherwood Droz’s El ABC de DtMF as a literal guide through Bad Bunny’s vocabulary. This glossary turns Puerto Rican street codes into shared knowledge without diluting their power. “It’s important to have those students in the class,” he told EFE, “because Bad Bunny is a global phenomenon.”

On any given day, translation is teamwork. A lyric about San Juan nightlife prompts someone to explain La Perla; a verse about hurricane recovery segues into diaspora remittances and mutual-aid networks. When a line hints at police violence, conversation widens to policing across the Americas.

The classroom’s diversity becomes its method. “We’re all translators here,” Yera said. “Not just language, but culture.”

The Super Bowl controversy —whether a Spanish halftime show is a celebration or a provocation —becomes an instant case study. Students argue that the United States already lives in Spanish, from Miami kitchens to California construction sites to New York subways. The outrage, they suggest, isn’t about comprehension but about power: who gets to speak and still be heard.

“This class shows that Spanish isn’t foreign in the U.S.,” Torres told EFE. “It’s already part of the soundscape.”

Studying the Island Now to Change What Comes Next

What began as a pop seminar has become something bigger, a mirror held up to America’s own soundtrack. Laguna pushes his students to think beyond fandom. They debate contradictions: the distance between celebrity and barrio, the commodification of Caribbean cool, and the responsibilities of global fame. “We can celebrate Bad Bunny and still question him,” Laguna said. “Critical love is still love.”

Assignments mix scholarship and autobiography. Students write reflections linking their lives to the island’s. One compares the reggaetón beat’s syncopation to the rhythm of bilingual households; another maps migration through the songs her mother played in a Chicago kitchen. The classroom becomes what Laguna calls “a rehearsal for public life”, a place to practice listening across difference before stepping into the world’s louder arguments.

For Torres, the lessons trail beyond campus. He sees in the course a blueprint for medicine that speaks to culture. “Understanding how austerity and migration affect people’s health makes me a better doctor,” he said.

Laguna sees a larger transformation. Universities, he argues, must stop treating Latino culture as a footnote. “You cannot understand the past, present, or future of this country without understanding the Latino community and Spanish,” he told EFE.

That conviction gives the course its urgency. When students gather for their final session, they will return to DtMF one more time, listening for what the beats remember and what they predict. The music will outlast the semester, humming through earbuds and essays, carrying the same question that started the class: what does it mean when the world’s loudest voice sings in Spanish?

Outside, winter presses against the Yale Gothic walls. Inside, a dozen students nod to the rhythm of an island that refuses to stay in the margins. When the Super Bowl cameras pan across a stadium singing along in Spanish, they’ll hear more than a pop spectacle. They’ll hear a syllabus made flesh: a nation learning to listen, a university catching up to the moment, and a beat that no longer asks permission to be heard.

Also Read: War Visions Haunt Latin America as Fiction Mirrors Reckless Policy