Mexican Telenovela Lobo Tests Justice Fantasies Amid ICE Street Protests

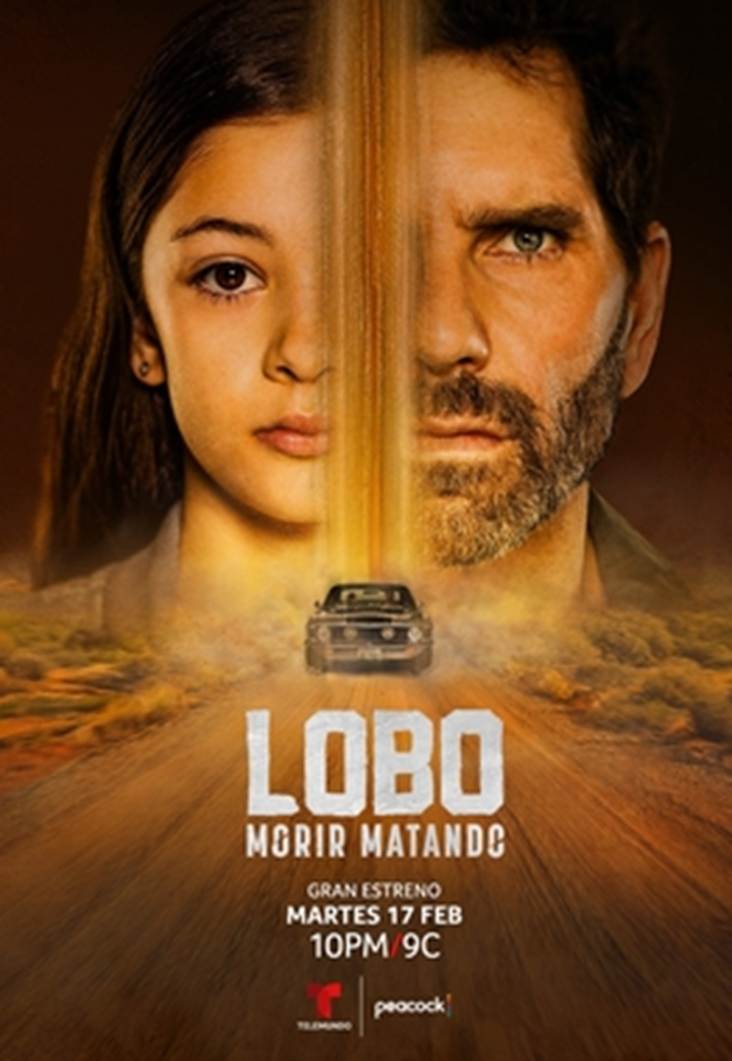

As protests target ICE and deportations reshape headlines, Telemundo’s Lobo, morir matando arrives with a risky promise: some inside security forces still try to protect ordinary Americans. Its story follows a refugee girl and an ex-cop who breaks rules.

A Cop Story in a Moment That Distrusts Cops

On the red carpet, the sound is its own weather. Cameras click in bursts. A line of microphones angles up toward faces that have learned to answer quickly, warmly, and with just enough control. This is where a series sells its mood before anyone at home sees the first scene.

Fátima Molina stands talking about police and protection at a moment when the word police can feel like a match. Her series, Lobo, morir matando, lands as protests flare against the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, known as ICE. The notes frame the backdrop plainly: a crisis of protests after massive deportations of migrants and the deaths of protesters like Renée Good and Alex Pretti.

That is the air around this show. Not fictional air. Real air.

“We are living such critical moments that you, I, and especially in the United States, but also worldwide, the only thing we want is for our police to take care of us, and I think that is what my character represents,” Molina told EFE.

It is a careful and revealing statement. What this does is set the argument the series wants to enter: in a public moment defined by anger at enforcement and fear about safety, can a story about security forces make room for nuance without sounding naive?

Molina says she feels proud to tell stories of “good police, who really want to do justice,” connecting that pride directly to the current protest climate described in the notes. The insistence matters not because it settles anything, but because it shows what the production is trying to recover: the idea that inside institutions many distrust, there are still individuals trying to do something decent.

The trouble is viewers have been trained by the broader TV ecosystem to look for justice in costumes, not uniforms. The notes point to a familiar pattern: screens full of series and films where the only avengers wear tights, like Batman or Spiderman. In that crowded landscape, Lobo slips in with a different pitch. No cape. No mask. Just a man with a breaking point.

When the Law Feels Wrong, and Justice Gets Personal

Lobo, morir matando tells the story of a refugee girl trying to reach the northern border after being pursued by a corrupt prosecutor’s office. During her flight, she relies on a former police officer, who takes justice into his own hands to protect her.

That premise is not subtle about its politics. Corruption inside the state. A child was pushed into danger. An adult who used to belong to the system and now no longer trusts it. The series is reaching for a familiar Latin American tension, the one that lives between law and justice, between procedure and survival.

Arap Bethke, who plays Lobo, describes him as something different from the shiny hero archetype viewers are used to. “He is not a superhero, far from reality, but someone who no longer believes in the system,” he told EFE.

Then Bethke goes to the heart of it. “He decided justice has to be done by his own hand because the law does not work,” he told EFE. “That is the difference between the law working and justice arriving. This works in a world where sometimes the law is not the right path.”

It is an argument that many people recognize, even if they do not agree with it. It is also the show’s moral risk. Build a protagonist around the idea that law fails and fists succeed, you are walking into a debate bigger than any one script. The wager here is that audiences can sit with that discomfort and still see what the series claims it wants to show: a drive to protect, especially when institutions feel compromised.

The notes push the character further. Leaving the system and using your own fists may not be orthodox, but it is what Lobo ends up doing so “the worst criminals one can imagine” are judged. That line does not promise gentle justice. It promises rough accountability.

In a moment of protests and deportations, that promise can read in more than one direction. For some viewers, it might sound like catharsis. For others, permission. That tension is not an accident. It is the series’ engine.

Protecting Childhood While Television Sells Violence

At the center of the power struggle is Renata, a girl whose childhood is cut short by an inheritance she did not know about, a subject the cast describes as alien and hard for her to understand, and not something that should be her concern.

That focus on a child is not just a plot. It is also a response to a wider anxiety the notes identify: what violence is doing to children, and how early it reaches them.

Dominika Paleta frames it as a basic principle, almost old fashioned in its simplicity. “I think in general the longer children have a childhood, the more they preserve play, the better,” she told EFE. She then recalls her own memory. “If I had something wonderful in the eighties, it was having a childhood free of practically television programs,” she told EFE. She contrasts that with the present: “The amount of narcos, of violence exposed on television is brutal, and I think there are many other stories that could be told,” she told EFE.

There is an everyday truth that does not need decoration. Kids watch what adults put in front of them. Adults also watch what the market keeps producing. Then everyone argues about consequences.

The notes underline how central this concern is in Mexico, describing children’s exposure to violence as one of the country’s main worries. They also cite a stark indicator from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI): a 45% increase in the number of adolescents charged between 2021 and 2023, a problem that puts thousands of young people at risk.

A show like Lobo, morir matando steps into that reality while also being part of the same television universe Paleta criticizes. It is a series driven by crime, corruption, and power struggles, even as it insists its moral center is the protection of a child. That is not a contradiction but a reflection of the region’s media dilemma: violence is both the warning and the hook.

Telemundo will premiere Lobo, morir matando on Tuesday on its international channels, alongside the return of another of its viral international programs, La casa de los famosos. The pairing is its own message. Drama and spectacle. Crime and celebrity. Two different kinds of attention, both powered by the growing relevance of a Latin accent in global media, as the notes put it.

And back on that red carpet, under the clicking cameras, the series makes its case in plain language. People want safety. People want justice. People want their children protected.

Not later. Now.

Also Read: Argentine Rock Legend Fito Páez Turns Cosquín into Memory