How Latin America’s Indigenous Rappers Are Rewriting the Soundtrack of Pride

Bad Bunny may headline the Super Bowl, but the deeper revolution is happening far from the stadium lights. Across Latin America, indigenous rappers are reviving languages once silenced by empire, using beats and verses to turn shame into swagger. Their hooks carry pride where textbooks failed, and the result is a cultural aftershock that no algorithm can contain.

From Halftime to Hearth

It’s tempting to see Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl ascent as just a pop spectacle—the NFL chasing youth and virality. But it’s more than that. His halftime show is the megaphone for a wider movement already roaring from the continent’s smallest studios: young artists rhyming in Quechua, Maya, and Nahuatl, turning forgotten tongues into the new sound of confidence.

The Super Bowl, the most global stage in American culture, is simply echoing what Latin America has been building. A Puerto Rican star at the center of the halftime show isn’t an exception—it’s a culmination. Bad Bunny’s success has opened space for the languages and rhythms once pushed to the margins.

That power shift is visible in the streaming charts—and in the stories behind them. From mountain towns in Peru to neighborhoods in Mexico City, a new generation is remixing its grandparents’ words with trap beats and hip-hop drums. What was once whispered in the home is now blasted from speakers.

Kayfex and the Quechua Comeback

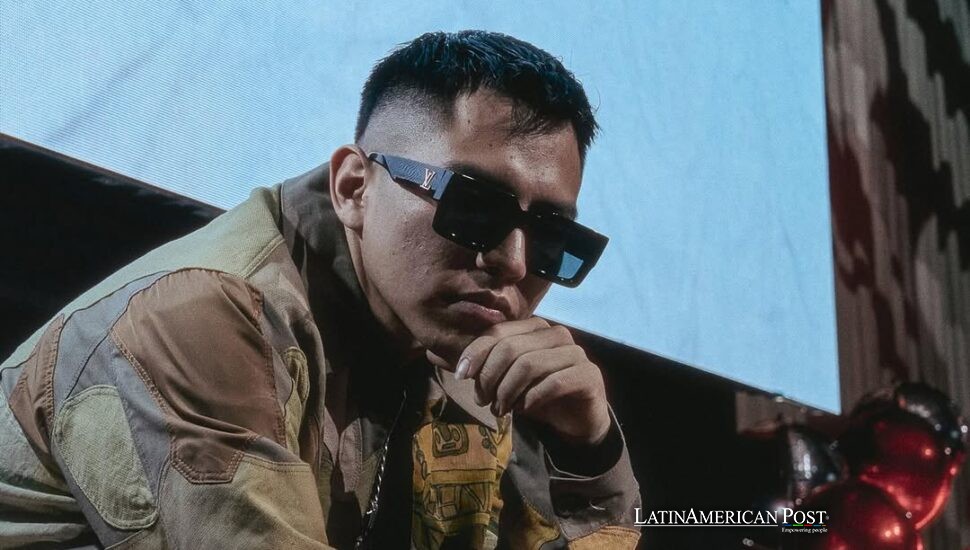

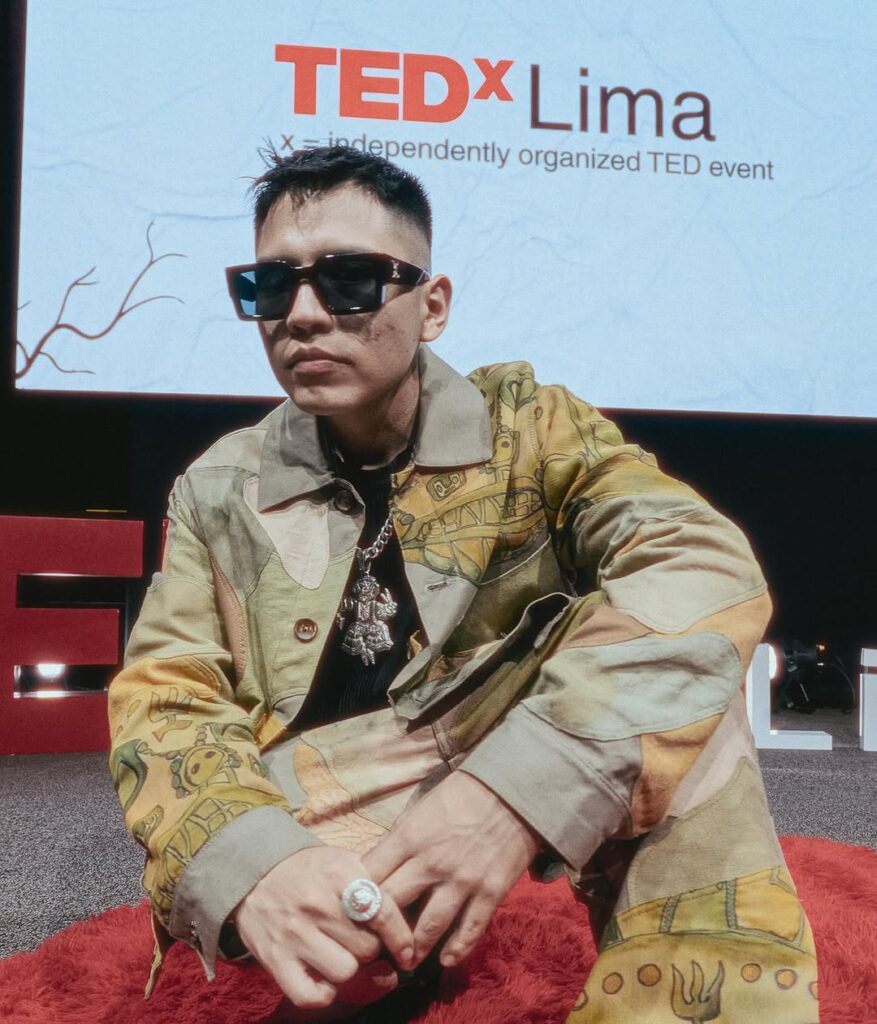

In the Andean city of Ayacucho, Luis Gavilan, better known as Kayfex, grew up hearing Quechua phrases from his grandmother, Luxcinan Sotelo, one of the last in his family to speak the language fluently. “Making music in our native languages reminds us where we came from,” he told The Sunday Times. That mission—part rebellion, part restoration—has turned him into one of Peru’s most celebrated new voices.

His 2023 record, Atipanakuy—Quechua for “to contest”—won a Latin Grammy. The album fuses Andean ritual sounds like the danza de tijeras with trap percussion and features collaborations with artists from Argentina to the U.S. “We work in a collaborative way, and that’s something we learned from our ancestors,” he said.

UNESCO lists Quechua as endangered, one of more than 500 indigenous languages across Latin America, nearly half of which are at risk of vanishing. Kayfex is fighting that erasure with rhythm and accessibility. “We try to use Quechua words that have a strong cadence, that are easy to pronounce so more people can repeat them,” he told The Sunday Times.

That’s not simplification—it’s strategy. By choosing the right syllables, Kayfex lets a student who has been teased for her accent rap along proudly. He turns embarrassment into participation. Artists like Renata Flores, who first went viral covering Michael Jackson in Quechua before writing her own anthems, and Mexico’s Pat Boy, who raps in Yucatec Maya, are doing the same. Together, they’re making music that reclaims what colonization tried to delete—and they’re making it cool.

Algorithms Meet Ancestry

The language revival is being powered by something ancient and something new: heritage and algorithms. Streaming and social media have dissolved the barriers that once fenced off “world music.” “Great music transcends borders,” said Brad Navin, CEO of The Orchard, which distributes Bad Bunny’s label, speaking to The Sunday Times. “Latin music is a wide-open genre, full of creative potential for a worldwide audience.”

A decade ago, a rapper performing in Quechua might have been a local curiosity. Now, a single TikTok can reach millions. Last year, Xiuhtezcatl Martínez, a Mexican-American rapper, posted a short clip of himself performing in Nahuatl while his aunt braided his hair. It exploded. “This clip of me singing in a language no one can understand had the ability to create this deep connection with people,” he told The Sunday Times.

That digital connection became physical. When he performed his first headline show in Mexico City, buses of children from his teacher’s village arrived uninvited. He brought them on stage to sing with him—in Nahuatl. “I don’t think these kids have ever experienced that kind of representation before,” he said.

It’s a perfect feedback loop: algorithms amplify visibility, and visibility restores dignity. Kayfex says that students who once felt ashamed now brag about their roots. “They start asking their grandparents about words, about songs. It’s creating curiosity,” he said. The beat is the bridge—the mind follows where the body already moves.

Even Bad Bunny, who doesn’t rap in indigenous languages, is part of that momentum. “Even though he’s rapping in Spanish and not in Taíno, I think a lot of people see themselves in his pride for his culture, his island,” Xiuhtezcatl told The Sunday Times. Pride travels faster than translation.

IG@Kayfex

The Politics—and Perils—of Visibility

But fame has its shadows. When an endangered language goes viral, who profits? Industry trends can turn authenticity into aesthetic, and artists into exotic content. Streaming platforms often mislabel songs in indigenous languages, burying them under “Latin” instead of creating searchable categories. True revival demands more than playlists—it requires infrastructure: studios, grants, metadata, and ownership.

“The risk is that they treat us like a flavor instead of a voice,” said Kayfex, wary of being commodified. To counter that, he returned home to Ayacucho to help younger musicians record locally. Flores mentors teens learning to write in Quechua. Xiuhtezcatl insists on community over celebrity—his concerts end with kids on stage, not fans behind barriers.

Their ethic is simple: don’t romanticize the roots—feed them. Build language into careers, not costumes. Make it viable, not viral.

That’s where the movement meets its challenge. Record labels love a moment, not a mission. But the artists understand what’s at stake: if this wave becomes a cycle, not a spike, it could be the most significant cultural revival Latin America has seen in generations.

From Puerto Rico’s global megastar to Peru’s mountain-born lyricists, the spectrum of Latin sound is widening, not narrowing. As Xiuhtezcatl put it, “It’s a cultural moment—but it’s also a moral one.” The music is not nostalgia; it’s a blueprint.

Also Read: Mexico Turns ‘The Smashing Machine’ into a Story About Heart, Not Hype

Bad Bunny may have the Super Bowl stage, but somewhere in Ayacucho, a kid is writing their first verse in Quechua. And that may be the sound that lasts longest—the quiet anthem of a generation reclaiming its voice, one verse at a time.