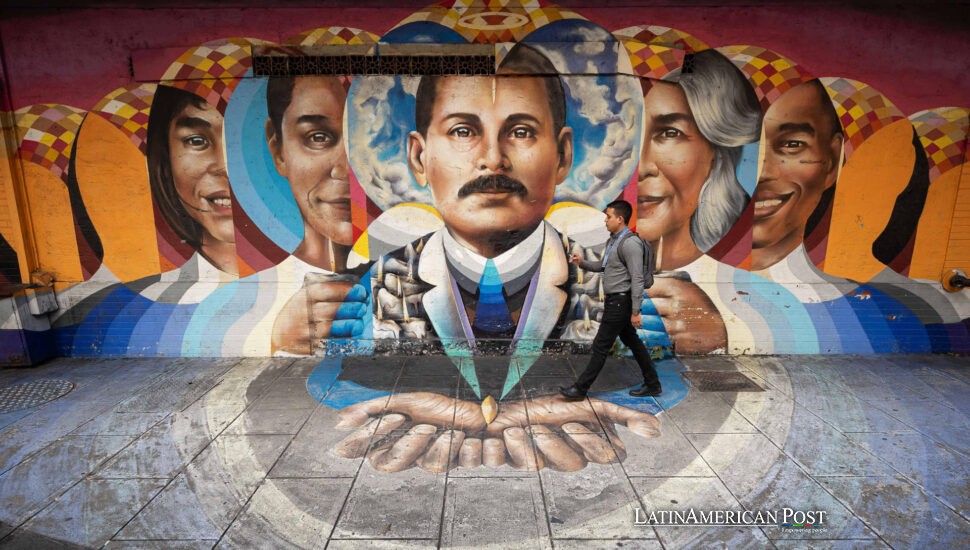

José Gregorio Hernández: Venezuela’s Saint of Science and the Poor

In a country exhausted by conflict, scarcity, and division, José Gregorio Hernández has become a rare point of agreement—a bridge between believers and skeptics, government and opposition, faith and science. A century after his death, the humble doctor from the Andean hills of Isnotú has been officially declared Venezuela’s first saint. But long before Rome confirmed it, his people already had.

A Saint Shaped by Science and Service

José Gregorio Hernández was born on October 26, 1864, in the quiet village of Isnotú, in the western state of Trujillo. His parents were modest but devout, and by the time he turned 13, they sent him to Caracas with one thing to trade for opportunity: a brilliant mind. He studied medicine at the Central University of Venezuela, graduating in 1888, and earned a scholarship to study bacteriology, pathology, and microbiology—the cutting-edge sciences of his time —in Paris.

He tried twice to become a priest in Italy, but the cloistered life didn’t suit him. So he returned home, convinced that medicine could be a vocation just as holy. He opened Caracas’s first bacteriology lab, taught medical students to treat illness as a mystery to be solved rather than a curse to be feared, and spent his evenings walking the barrios to treat the poor who couldn’t afford hospital care. His door was open to everyone, and he charged only what his patients could pay—often nothing.

“He treated the body as a science and compassion as a duty,” one historian told EFE. That simple credo made him both healer and teacher, scientist and servant. On June 29, 1919, Hernández left home to deliver medicine to a patient. He was crossing the street when one of Caracas’s first cars struck him. He died on the spot.

The city mourned as if it had lost a relative. His funeral stretched for blocks. In homes across Venezuela, families began lighting candles beside his photo, whispering petitions for healing. Within days, the “doctor of the poor” had become a folk saint.

Canonization as Rare Common Ground

In today’s Venezuela—fractured between chavistas and opposition, and between despair and endurance—Hernández’s canonization became something unheard of: consensus. Both government and opposition embraced it for their own reasons, but for once, the tone was reverent, not bitter.

President Nicolás Maduro called the canonization “an act of justice for a man who in life protected the most humble,” adding that his sainthood had “great meaning for a people who feel threatened by the greatest military power in history,” a reference to the United States, according to EFE.

Opposition leaders, meanwhile, used the moment to plead for mercy at home. They urged the government to release political prisoners as a gesture worthy of the saint’s spirit. “We ask for medidas de gracia—acts of grace—so that those unjustly imprisoned can share in the hope this canonization brings,” the Venezuelan Episcopal Conference said in a statement quoted by EFE.

Even the Attorney General’s Office, often combative, softened its rhetoric, insisting no one was jailed for politics but acknowledging “the people’s devotion to the saint who belongs to all Venezuelans.”

For one Sunday, the arguments quieted. The government, the church, and the street all turned their eyes to Rome, where the Vatican’s formal recognition was set to coincide with the canonization of another Venezuelan figure, Sister Carmen Rendiles. It was a rare day when Venezuela’s fractured identity felt whole.

Miracles, Syncretism, and the Long Road to Rome

The road to sainthood is long, even for the beloved. Hernández’s process began in 1949, thirty years after his death. He was declared Servant of God in 1972 and then Venerable decades later. The miracle that opened the final door came from Guárico, in 2017, when ten-year-old Yaxury Solórzano Ortega was shot in the head during a robbery. Her doctors said survival was impossible. Her mother prayed to José Gregorio. The girl lived—and recovered fully.

“It was a healing that science could not explain,” said Bishop Tulio Ramírez, vice postulator of the cause, in an interview with EFE. “That’s what made the miracle undeniable.”

But Venezuelans didn’t need Rome’s approval to believe. For generations, Hernández’s portrait has stood beside the Virgin Mary and Saint Anthony on household altars, candles flickering beside stethoscopes and medicine bottles. His image also found its way into the syncretic folk traditions of Maria Lionza and other popular devotions. “He listens to everyone, no matter the prayer,” said María Luisa Gómez, a street vendor who has kept a candle for him since childhood, speaking to EFE outside Caracas’s La Candelaria Church.

That universality sometimes made church authorities uneasy, as they worried that folk rituals might blur Catholic orthodoxy. Yet the people’s devotion proved irresistible. The Vatican might canonize one miracle, but Venezuelans claim thousands: a cured illness here, a passed exam there, a debt paid, a child found. For the faithful, José Gregorio has never stopped making rounds.

From Isnotú’s Hills to La Candelaria’s Shrine

After Hernández’s death, mourners crowded his grave at the Cementerio General del Sur in Caracas, leaving so many candles that one vigil caused a fire that burned his headstone. In 1975, the church moved his remains to La Candelaria, where thousands still visit each week. The walls are lined with photos, crutches, and handwritten thank-yous—an improvised medical chart of gratitude.

Isnotú, his birthplace, has become a pilgrimage site. There, pilgrims climb the hill to a small chapel, carrying flowers and whispered hopes. “People come with tears and leave with peace,” said Father José Jiménez, guardian of the shrine, speaking to EFE. “He is the saint who heals the soul by reminding us to care for others.”

Hernández’s canonization doesn’t erase Venezuela’s divisions or economic hardship, but it offers something more profound: a model of public life grounded in compassion, not power. A doctor who treated the sick without judgment, a scientist who believed faith and reason could coexist, a citizen who saw knowledge as service—he embodies the Venezuela many still long for.

His sainthood arrives in a century defined by fatigue, mistrust, and survival. Perhaps that’s why it matters so much. In a world that often rewards spectacle, José Gregorio Hernández’s holiness remains quiet: a knock on a door, a house call after midnight, a hand on a fevered forehead.

Also Read: Palenque’s Next Revolution: Colombia’s First Free Black Town Seeks Freedom From City Hall

More than a saint, he is a reminder that healing begins where service meets grace—and that even in darkness, compassion can still find its way home.