Latin America Steps Away from Churches but Not from God

In Latin America, the census box is changing faster than the soul. New Pew Research Center surveys show Catholic identity falling across Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, as “nones” rise—yet belief in God stays fiercely high.

A Shrinking Label in A Region That Still Prays

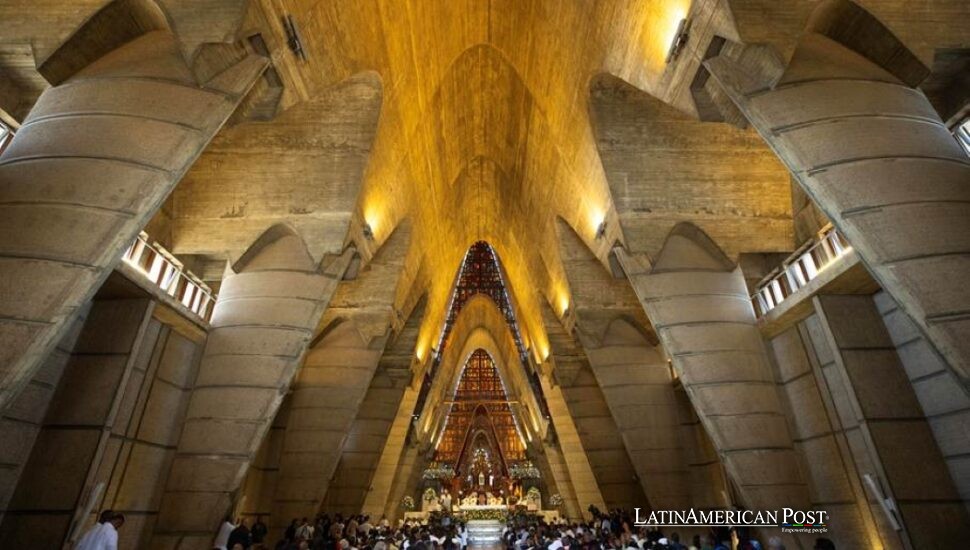

On paper, the shift looks blunt: fewer Catholics, more people who say they are atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular.” But in Latin America, religion has never lived only on paper. It lives in the way a mother touches a forehead before a long bus ride, in the neighborhood saint whose name becomes a shortcut for protection, in the candle lit not as doctrine but as habit, memory, and love. So when Pew Research Center reports that the Catholic share of the population has shrunk over the last ten years in some of the region’s most populous countries, the real story is not simply a church losing market share. It is a continent revising its vocabulary of belonging—sometimes quietly, sometimes with rebellion, often with a complicated tenderness.

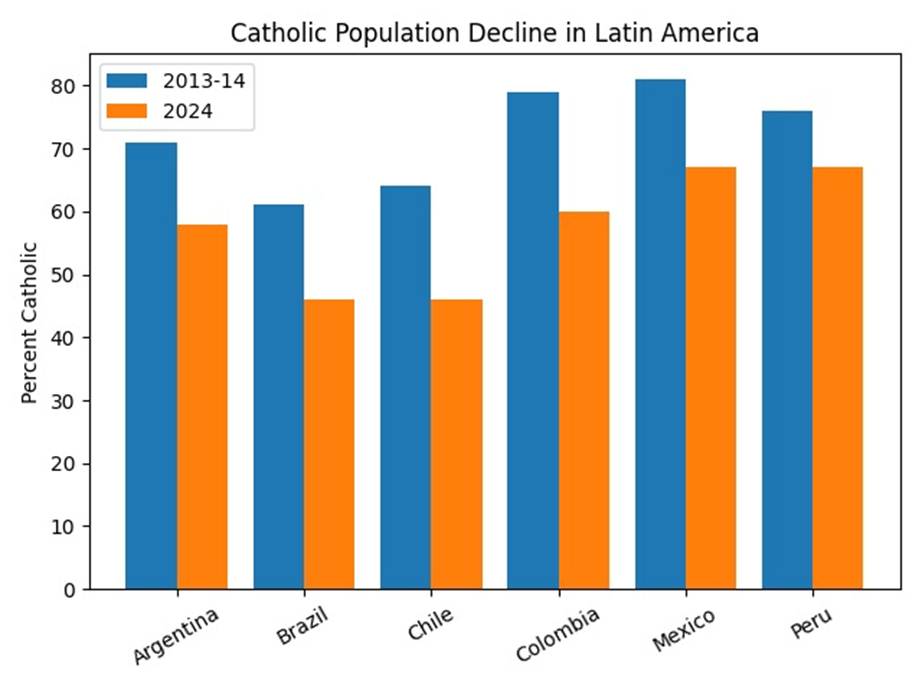

According to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in spring 2024, which included more than 6,200 adults in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, Catholicism remains the largest religion in each of these countries. Yet “largest” no longer means what it used to. Today, Catholics make up between 46% and 67% of the adult population in each country surveyed, while the share of adults who are religiously unaffiliated ranges from 12% to 33%. Over the past decade, Catholic shares fell by nine percentage points or more in all six countries, while the unaffiliated rose by seven points or more—and in several places, the “nones” now outnumber Protestants.

Still, the region refuses to fit into the familiar European narrative of belief draining out of society like water from a cracked cup. By several measures in the same Pew Research Center data, Latin Americans remain strongly religious on average. Around nine-in-ten or more adults surveyed in each country say they believe in God. In Brazil, that figure reaches 98%; in Chile, it is 89%. In Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, about half or more say religion is very important in their lives, including 79% of Brazilians and 57% of Colombians. Prayer remains common: majorities of Brazilian, Colombian, and Peruvian adults say they pray at least once a day, and across all six countries, daily prayer ranges from 39% in Argentina to 76% in Brazil.

The contradiction is only a contradiction if you imagine faith as a single ladder—up or down, believer or nonbeliever, church or nothing. Latin America tends to move sideways. People step away from institutions while holding on to the metaphysical. They reject a label while keeping a ritual. Even among the unaffiliated adults surveyed, majorities still say they believe in God. In Mexico, about three-quarters of “nones” say they believe in God—an answer that sounds less like secular certainty and more like a region insisting that the universe remains populated, even if the pew is not.

The earlier survey Pew Research Center conducted in 2013–2014 allows a direct comparison on two core questions—religious affiliation and belief in God—offering a decade-long snapshot of how the region has shifted. Most other measures from 2024 cannot be directly compared because the questions are new or have changed wording. But the affiliation picture alone is enough to show a tectonic motion under everyday life.

Where The Former Catholics Went, And What They Kept

A decade ago, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru all had Catholic majorities, with roughly six-in-ten or more adults in each identifying as Catholic. Today, that dominance has thinned. In 2024, roughly half of Brazilians and Chileans identify as Catholic—46% in Brazil and 46% in Chile. Argentina stands at 58%, Colombia at 60%, and Mexico and Peru at 67% each. Catholicism has been declining in all these countries at least since the 1970s, according to estimates from the World Religion Database, a reminder that today’s headlines are often the visible crest of a longer, deeper wave.

The most dramatic change is not Protestant growth, which many outsiders once treated as the region’s only alternative future. Protestantism has remained relatively stable across these countries, according to Pew Research Center. In Brazil, the most Protestant of the six surveyed, 29% of adults identify as any kind of Protestant today, compared with 26% in 2013–2014. Pentecostal Protestantism remains widespread, though Pew Research Center notes that the percentage of Protestants who are Pentecostal has declined over the past decade as other traditions have grown.

Instead, the big movement is toward “nothing in particular.” The share of adults who are religiously unaffiliated has roughly doubled in Argentina to 24%, Brazil to 15%, and Chile to 33%; tripled in Mexico to 20% and Peru to 12%; and nearly quadrupled in Colombia to 23%. In Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico, unaffiliated adults now outnumber Protestants. Mexico offers the cleanest contrast: two-in-ten Mexican adults identify as atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular,” while about one-in-ten identify with any branch of Protestantism.

But the most human part of this story is not the percentages; it is the act of leaving. Pew Research Center ties Catholic decline and unaffiliated growth in part to religious switching—adults raised Catholic who no longer identify with it. Across the six countries, around two-in-ten or more adults say they were raised Catholic but have since left Catholicism. In other words, the change is not only generational replacement; it is personal decision, lived biography.

In Colombia, 22% of adults say they were raised Catholic but no longer identify that way. That includes 13% of all adults who were raised Catholic and now identify as atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular,” plus 8% who have become Protestant and 1% who identify with another religious group. Brazil is the standout: former Catholics there are more likely to now be Protestant (13% of all adults) than unaffiliated (7%). In Peru, the former Catholics divide more evenly—9% of all adults have become Protestant and 7% have become “nones.”

Yet in all six countries, most adults still identify with a religion, and belief in God remains overwhelming. Religious affiliation ranges from 66% in Chile to 88% in Peru, including Catholics, Protestants, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and also Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, and Indigenous religions such as Umbanda and Candomblé, alongside smaller shares of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. The region’s religious map has never been a simple two-color drawing. It is layered, braided, and full of local dialects of the sacred.

The categories also behave differently in everyday life. Pew Research Center reports that Protestants are generally more likely than Catholics and “nones” to say religion is very important in their lives. In Chile, 75% of Protestants say religion is very important, compared with 48% of Catholics and 9% of unaffiliated adults. Protestants are also more likely to attend services weekly or more often; in Argentina, 63% of Protestants say they attend at least weekly, compared with 12% of Catholics and 2% of “nones.” Yet Catholics carry a different kind of visibility: they are much more likely to wear or carry religious items or symbols. In Colombia, six-in-ten Catholics say they do this, compared with two-in-ten or fewer among Colombian “nones” and Protestants—an everyday reminder that Latin American Catholicism often lives not just in belief but in objects that accompany the body.

And then there’s a detail that feels distinctly Latin American: Catholics and unaffiliated adults are generally more likely than Protestants to believe that parts of nature—mountains, rivers, trees—can have spirits or spiritual energies. In Brazil, roughly six-in-ten Catholics and “nones” hold that belief, compared with about half of Protestants. It reads like a region where the sacred is not only above but also around—embedded in landscape and memory, sometimes surviving even when institutional loyalty fades.

The Venezuelan Diaspora and The Faith of Return

If religious identity is changing, so is the region’s sense of home, and the two stories meet in the lives of Venezuelans scattered across Latin America who are weighing whether to return. In the text provided, some migrants say they are cautiously hopeful after the U.S. ouster of long-time leader Nicolás Maduro raises hopes for democratic elections and a way out of economic collapse. Since 2014, about a quarter of Venezuela’s population has fanned out across Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain, and the United States, fleeing what the text describes as an oil-dependent economy crippled by mismanagement. The exodus—about eight million people—has transformed demographics across the Americas and shaped politics far beyond Venezuela’s borders.

In Colombia, which the text describes as hosting Latin America’s largest Venezuelan migrant population, Juan Carlos Viloria, a doctor who helps run a migrant advocacy group, speaks with the kind of hope that sounds like duty. “I want to return to my country, I want to help rebuild,” he says. But he also describes the gravity pulling people back into fear: with Delcy Rodríguez, identified in the text as Maduro’s former vice president, tightening her grip on power, migrants weigh the risk of repression and the reality of economic insecurity. He notes that border communities in northeastern Colombia have seen a rise in people crossing into Colombia to earn some cash while the situation stabilizes—an improvised life, built from crossings.

Other voices in the provided text hold both longing and skepticism in the same breath. Nicole Carrasco, who moved to Chile in 2019 after her father was arrested, fears little has changed for political prisoners and their families. “It is not as if Venezuela is free yet—there are still many very bad people in power,” she says, while also longing to see family and eat traditional foods like arepas. The text notes that opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner María Corina Machado, whose candidate was widely seen as the legitimate winner of the 2024 election that Maduro was accused of rigging, has called for a transition of power as soon as possible so Venezuelans can return home.

In Panama, the provided text captures the mood of people mid-journey, suspended between countries and outcomes. Luis Díaz, traveling back to Venezuela after a year in Mexico, says, “I don’t know whether it’s good or bad. Now they’ve done what they’ve done, something different is going to start.” Omar Álvarez, also passing through Panama on his way home, offers a more declarative faith, the kind that migrants often learn to speak because despair is too expensive. “All of us outside Venezuela, I think we can come together and recover our country by working together, like we have always done in every country we’ve arrived in,” he says. “With all of us united, our country’s economy will rise again.”

Read alongside the Pew Research Center findings, the diaspora story sharpens the meaning of Latin America’s “nones.” Leaving Catholicism, for many, does not mean leaving belief; it means leaving an institution while keeping the language of hope, protection, and moral accounting. Leaving a country can work the same way: you abandon a structure that failed you while still believing in the possibility of return. In both cases, the region shows a stubborn pattern: identity changes, but yearning remains.

So the decade-long shift captured by Pew Research Center is not a simple religious decline. It is a reorganization of how Latin Americans name themselves—Catholic, Protestant, nothing in particular—while continuing to pray, believe, carry symbols, and search for meaning in nature and community. Catholicism may be shrinking as a census label across Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, but the sacred has not packed its bags. In Latin America, even disbelief often speaks with an accent of belief, and even the unaffiliated keep reaching—toward God, toward home, toward something that says the future can still be repaired.

Also Read: Mexico’s Water Reckoning Leaves Texas Thirsty and Northern Borderlands on Edge