Peru’s Quixote Treasure Finds New Windmills In Royal Ink Dreams

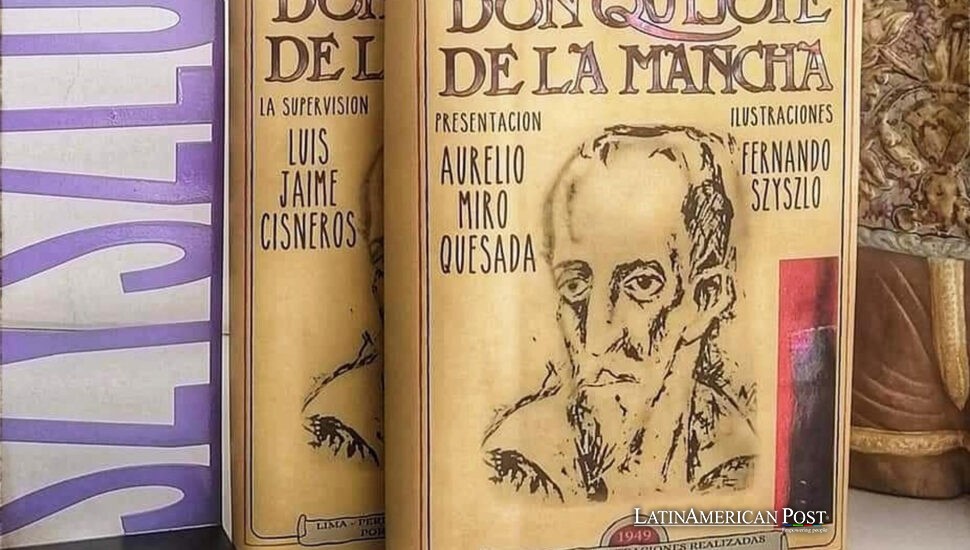

In a Lima gallery, a rare 1949 Peruvian edition of Don Quijote de la Mancha has returned to the light. Illustrated by a 22-year-old Fernando de Szyszlo, the book now inspires collector Horacio Rico to dream of giving it a new public life—with royal signatures and cultural prizes for future generations.

The first Quixote printed in Peru

For decades, this singular edition seemed almost mythical, whispered more than seen. Conceived in 1947 by journalist Aurelio Miró Quesada and linguist Luis Jaime Cisneros, it became a reality in 1949 under editor Pablo Villanueva: the first Quixote ever printed in Peru. Their ambition was bold—to anchor Cervantes’ classic in a Peruvian press tradition while entrusting its imagery to a young artist who would one day become a pillar of Latin American abstraction.

That artist was De Szyszlo, barely in his twenties but already fearless. The centenary of his birth, celebrated this year, has revived the book as both homage and cultural challenge. Rico, the collector who rescued and restored hundreds of copies, calls it “a huge dream.” He now owns some 400 volumes and most of the original imagery that gave the edition its force. “Having 400 copies and the majority of the drawings, I’ve thought of placing part of the works with the Instituto Cervantes,” he told EFE, pointing to Spain’s cultural institution as the ideal steward for the next chapter.

A young Szyszlo, steel plates, and secret muses

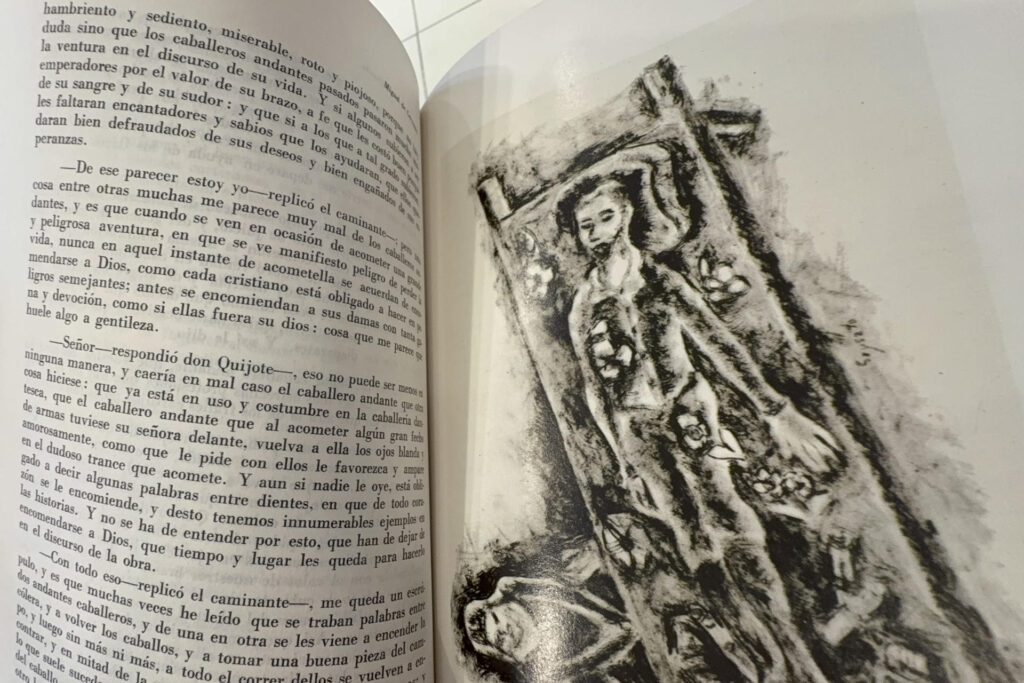

The contribution of the 22-year-old artist was audacious. Instead of drawing on paper, he created forty aquatints on steel plates, each image born from the slow dialogue of burin, acid, and light. “He would read the book and elaborate the drawings as he went,” Rico explained to EFE, describing how De Szyszlo lived with Cervantes’ prose for more than two years.

The results remain strikingly modern: spare lines, monumental silhouettes, landscapes that oscillate between the Andes and La Mancha. Hidden in the figures are tributes to his circle. For Sancho Panza, De Szyszlo is said to have drawn inspiration from his friend, poet Octavio Paz; for Dorotea, disguised as a shepherdess, he found his model in his wife, the Peruvian poet Blanca Varela.

The Quixote that emerged was not merely illustrated—it was reimagined. Cervantes’ Renaissance prose collided with a mid-century Latin American sensibility. Rico safeguards twenty-seven of the aquatints, together with the intact volumes, making his collection a rare bridge between literature and the visual arts, between national tradition and continental avant-garde.

A book shelved by a coup, rescued by devotion

The afterlife of this Quixote has been as quixotic as its hero’s journey. A 1992 reissue was poised for release during the quincentennial of Columbus’s voyage. Then came April 5, 1992: President Alberto Fujimori’s self-coup. Cultural programs froze, institutions shuttered, and the book disappeared into closets and warehouses.

“It set off with such bad luck that the book was put away for 33 years,” Rico recalled to EFE. He shrugs at the memory, half lament, half relief. “I have rescued it, and for me it is a great joy that all that has happened because I think the book is going to have a beautiful ending—and I want that ending to be for everyone.”

Reviving the 1949 edition also honors its intellectual midwives. Cisneros, who went on to receive the Palmas Magisteriales at the rank of Amauta, and Miró Quesada, who later directed El Comercio and served the Peruvian Academy of Language, had both dreamed of linking Peru’s print culture to the global masterpiece. Their ambition feels urgent today in an age of fractured attention and fugitive reading: to root global literature in local soil and print.

From collector’s vault to public prize

Rico’s plan is as theatrical as it is practical. He wants the volumes not locked away but woven into civic life. “I want Princess Leonor and her father, King Felipe, to sign this book,” he told EFE. “That these books be prizes, which must be earned with a poem or a cultural action.”

It is a Cervantine idea—turning a bibliophile’s treasure into a living award. Rico envisions a partnership with the Instituto Cervantes, a partial deposit of plates and copies, and an annual ceremony where the book becomes both prize and provocation. In his vision, a teenager’s first great poem or a community’s cultural project could be honored with a copy of this Peruvian Quixote, carrying not only De Szyszlo’s aquatints but royal ink.

Such a gesture would transform the archive into a civic engine: a classic that inspires new classics, a book that births more books. “The important thing,” Rico said, looking at the black-and-white pages, “is that this is the only book in Peru printed with the figure of the master of the century. The master of the century turned 100, and I believe this homage is owed to him.”

The “master,” of course, is De Szyszlo. Yet Rico’s words land, inevitably, on Cervantes too—on the stubborn endurance of a knight who tilts at windmills and a squire who never stops following. Their story now has a new route: from a Lima atelier in 1949 to a palace signature in Madrid, from steel plates to school prizes, from decades of exile on a warehouse shelf to a public life among readers.

Also Read: Latin American Deportations Leave Pets Stranded as U.S. Shelters Plead for Help

A book stepped back into a gallery this summer and asked to be reread, aloud and together. If Rico succeeds, Peru’s Quixote will keep riding—armed with aquatints, a royal flourish, and the conviction that literature is not just consumed but created anew with each generation.