Argentina Patagonia Pumas Found A Penguin Buffet And Changed Society

In Patagonia, Argentina, pumas returning to Monte León National Park have learned to hunt Magellanic penguins, turning a protected beach into an ecological laboratory. New research shows this prey switch is reshaping territory, tolerance, and conservation dilemmas along Argentina’s Atlantic coast.

A Return With Consequences

On the southern Atlantic coast, Monte León National Park holds two histories at once: ranching and return. In the 20th century, sheep operations across Patagonia helped force pumas out. When the park was established in 2004, the big cats began filtering back into a protected strip of shoreline. But the place they returned to had already improvised. A mainland breeding colony of Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) had taken hold on the beach, swelling to roughly 40,000 breeding pairs.

That penguin boom created what ecologists call a subsidy: a dense, predictable pulse of food. Not long after the park’s creation, penguin remains started appearing in puma scat, and early assumptions fell apart. “We thought it was just a couple of individuals,” study coauthor Mitchell Serota, an ecologist at Duke Farms in New Jersey, told Live Science. “We noticed a ton of puma detections” near the colony. Serota conducted much of the work as a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, and the pattern is a reminder that protection rarely recreates a prehuman baseline.

Penguin Season, Puma Politics

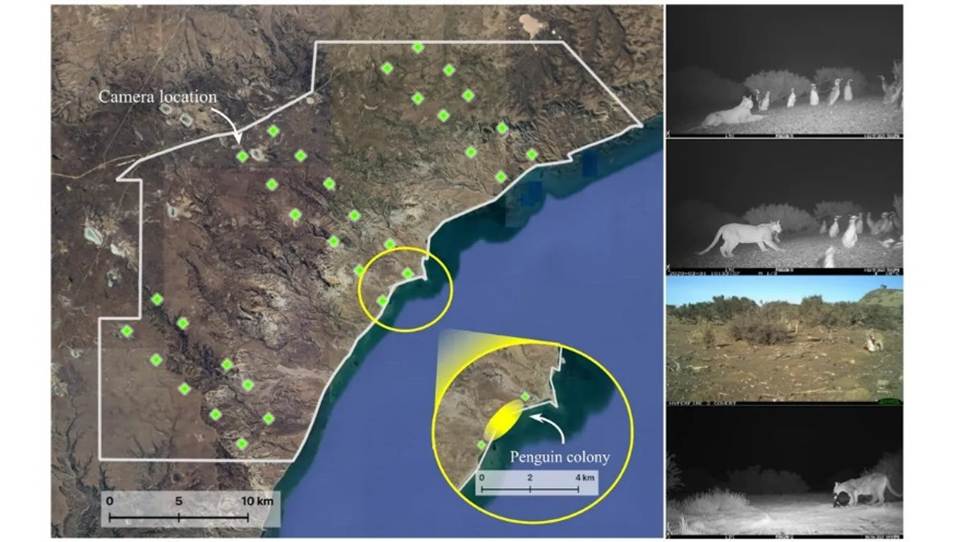

The team’s findings, published on Wednesday (December 17) in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, show how quickly a predator can reorganize its life around that new beach larder. Researchers combined camera traps with GPS collars to track 14 pumas and survey kill sites across field seasons from 2019 to 2023. The cats did not behave as a single population: 9 individuals hunted penguins; 5 did not. When penguins were ashore during the breeding season, the hunters stayed close to the colony along a 1.2-mile (2-kilometer) stretch of beach. When the birds migrated offshore in summer, those same cats ranged about twice as far, stretching back into the interior where prey is less concentrated, and distances are punishing.

If the movement patterns are logical, the social patterns are startling. Adult pumas are generally solitary, spacing themselves out to avoid fights and to secure enough prey for themselves and their kittens. Yet around the colony, the study recorded 254 encounters between pairs of pumas that both ate penguins, compared with just 4 encounters in which neither did. Most meetings happened within 0.6 miles (1 km) of the penguin colony. The study also reports that puma density in the park was more than twice the highest previously recorded concentration within Argentina. Abundance, it suggests, can soften competition and allow neighbors to coexist—changing “rules” that many conservation plans quietly assume are fixed.

Managing a New Wild

Serota underscored the broader point in comments quoted by Live Science: “Restoring wildlife in today’s changed landscapes doesn’t simply rewind ecosystems to the past.” Instead, he said, it can create “entirely new interactions.” Debates in Conservation Biology and Trends in Ecology & Evolution have warned that past human decisions continue to shape present-day nature. In an email to Live Science, Juan Ignacio Zanon Martinez of Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) wrote that managers need strategies “grounded in how ecosystems actually function today.” And as Javier Ciancio, also at CONICET, told Live Science, it is a “complex situation” because two native species are interacting under changed conditions—raising questions about how smaller, newer penguin colonies might fare on the mainland.

Next, Serota’s team plans to examine how this coastal feast affects other prey, including the guanaco (Lama guanicoe), a wild camelid related to the llama. The question is quietly political, too: when penguins pull pumas toward the beach, what happens inland, and who bears the costs or benefits beyond park boundaries where ranching remains a livelihood? For conservation in Argentina, the lesson is uncomfortable but useful—monitor what is happening now, not what we wish had happened then. On Argentina’s Atlantic edge, the experiment is already running. The park did not resurrect a vanished past; it revealed a living present—one where penguins, pumas, and people negotiate a new balance in real time, right now, too.

Also Read: Panama Forest Bats Hunt Like Lions And Challenge Nature’s Rules