Dominican Republic Cave Bones Reveal Bees’ Strange Ancient Nursery Secrets

Deep in Cueva de Mono in the Dominican Republic, scientists found bees that never fossilized—only their nests, sealed inside tooth sockets. The discovery, reported in Royal Society Open Science, turns owl pellets and old bones into a Caribbean time capsule.

Where the Owls Fed, the Bees Built

Long before anyone arrived with headlamps and sampling bags, giant owls hunted, swallowed prey, then regurgitated bone-rich pellets onto a cave floor. Over thousands of years, those pellets accumulated into thick layers of skulls, jaws, and vertebrae—grisly evidence of predation, and a landscape of protected hollows waiting to be used.

The new claim is that bees used those hollows as nurseries. In Trace fossils within mammal remains reveal novel bee nesting behaviour—published in R Soc Open Sci on 1 December 2025 (12 (12): 251748)—Lázaro W. Viñola-López, Mitchell Riegler, Selby V. Olson, Johanset Orihuela, Julio A. Genaro, and América Sánchez-Rosario describe smooth, oval structures lodged in tooth sockets of rodent skulls. The shapes were too orderly to dismiss as mud; the authors interpret them as petrified nests of prehistoric bees—trace fossils of brood cells built inside bone, then hardened by time and minerals.

The story also carries a distinctly Latin American fragility: the cave almost became plumbing. Viñola-López, now at the Field Museum in Chicago, first encountered Cueva de Mono during doctoral work at the Florida Museum of Natural History, after a colleague proposed excavating a site a local landowner had unsuccessfully tried to turn into a septic tank. Inside were thousands of bones deposited over about 20,000 years. The team has identified roughly 50 vertebrate species, including sloths, lizards, tortoises, and even crocodiles. The cave is especially rich in extinct relatives of hutias. Many bones appear partially digested, suggesting prehistoric relatives of barn owls carried them in before soil washed through and filled cavities with sediment.

Osnidum and the Craft of Hidden Mothers

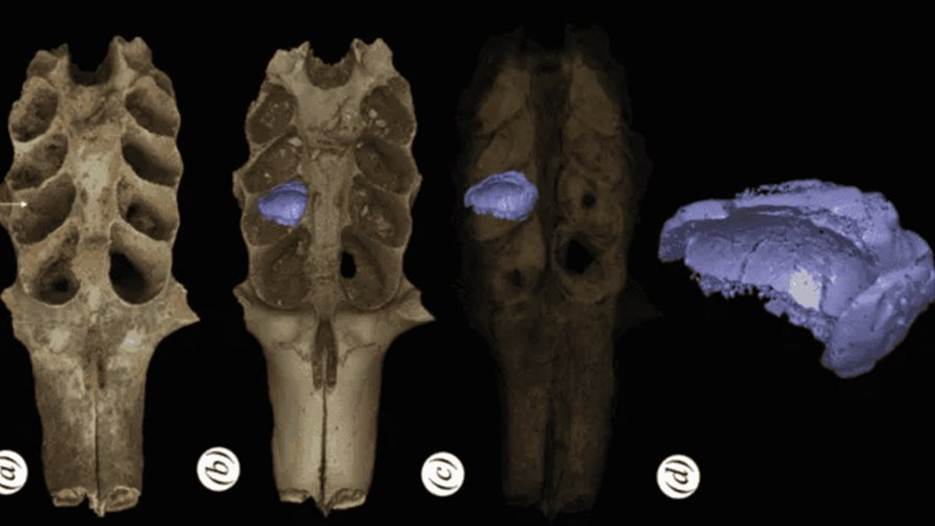

In the lab, while cleaning rodent skulls, Viñola-López noticed tooth sockets containing oddly smooth forms that reminded him of fossilized insect cocoons. To study them without breaking them, the researchers used micro-CT scanning and created three-dimensional digital models—each smaller than a pencil eraser. The scans revealed layered construction, not random fill, and some chambers even held grains of ancient pollen, the residue of food stored for larvae.

Bees are usually underground builders, lining brood cells with a waxy, waterproof coating that protects developing young and the pollen stores they eat. Here, the raw material was bone. “It was this perfect situation with lots of decomposing fossils that lacked teeth,” Viñola-López said. “These chambers provided protection for the bees’ nests.” The team also found similar traces tucked into the recesses of a rodent vertebra and inside a cavity within a ground sloth’s tooth, suggesting the behavior was not confined to one animal’s remains.

The bees themselves were not preserved, which makes the discovery feel even more human: meaning extracted from absence. Phillip Barden, an evolutionary biologist at the New Jersey Institute of Technology who was not involved in the work, said the nests provide a “wealth of data” about ecology and behavior. The researchers propose that a solitary bee made the traces and named them Osnidum, from Latin roots meaning “bone” and “nest.” Their evidence suggests repeated use over hundreds—or even thousands of years. In one tooth socket, they found six generations stacked on top of one another. The study describes this as the first known bee to build nests within animal bones and only the second known bee to nest in caves. Riegler argues the insects likely lacked better options in a coarse limestone landscape where little soil accumulates and what exists washes into caves.

An Island Archive Worth Protecting

It is hard to read this from the Dominican Republic without thinking about what nearly disappeared. A cave that almost turned into a septic tank reveals a novel nesting strategy, not because the evidence shouted, but because someone looked closely at a tooth socket and treated it as more than debris. Across the Caribbean, where development pressure often outruns research budgets, “unknown” can be the most endangered category of all.

That mismatch—between fast land use and slow discovery—runs through the Caribbean. A cave can look disposable until science shows it is an archive. Once revealed, stewardship becomes civic work too.

The nests are, in their own way, a fossilized act of care. A brood cell is built for a future the builder will never witness, a wager made in darkness with whatever material is available. Barden captured the blunt poetry: “Any port in a storm, or any skull in a cave.” In Cueva de Mono, that line lands as both humor and warning—about how inventive life can be, and how easily the places that preserve those inventions can be erased before we ever learn their names.

Also Read: Panama Forest Bats Hunt Like Lions And Challenge Nature’s Rules