Mexico’s AI Gold Rush Meets a Thirsty Reality: Can a Colonial City Power the Cloud Without Draining the Well?

From the highway, Querétaro still looks like a painter’s trick of the light—the ochre of 18th-century stone punched against a blue sky, the famous aqueduct’s 74 arches striding over rooftops as if time itself were load-bearing. Up close, the postcard has new margins. Windowless rectangles rise behind walls topped with cameras. Cranes swing over pads strung with high-voltage cable. Fiber conduits braid into substations the size of supermarkets. The city that once grew on water now grows on bandwidth.

A Colonial Postcard, Now a Server Farm

Microsoft broke ground here. So did Amazon Web Services. Brazilian-backed Ascenty and São Paulo’s ODATA followed. Others are parked behind construction fences, their names yet to be stenciled onto perimeter signage. State officials talk about more than $10 billion in data-center investment over the next decade and gesture to the proof: caravans of switchgear and chillers crawling the toll road, hotel lobbies with lanyards and English, a skyline where cold-aisle space is a growth metric.

“The demand for AI is accelerating the construction of data centres at an unprecedented speed,” said Shaolei Ren, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of California, Riverside, in an interview with the BBC. Generative models crave compute; compute eats power and cooling; power and cooling demand places that can deliver both without years of grid-queue purgatory. “The power grid capacity constraint in the US is pushing tech companies to find available power anywhere they can,” Ren told the BBC. Land is cheaper here. Permits—when the governor’s office leans in—arrive faster.

“It’s a very strategic region,” said Arturo Bravo, Ascenty’s Mexico country manager, walking a visitor through a humming hall where the loudest sound was the rind-peel whine of fans. He told the BBC he can point north to Mexico City, south to ports, east and west to interconnections. “Querétaro is right in the middle, connecting east, west, north and south,” he said. The state and city “identified [the area] as a technology hub,” smoothing zoning and regulation. In his forecast, the skyline is coded into the algorithm. “I do see it just kind of progressing and progressing, with a new data centre there every few years,” he said. “The industry will continue to grow as AI grows.”

Water, Heat and the Hidden Costs of Cool

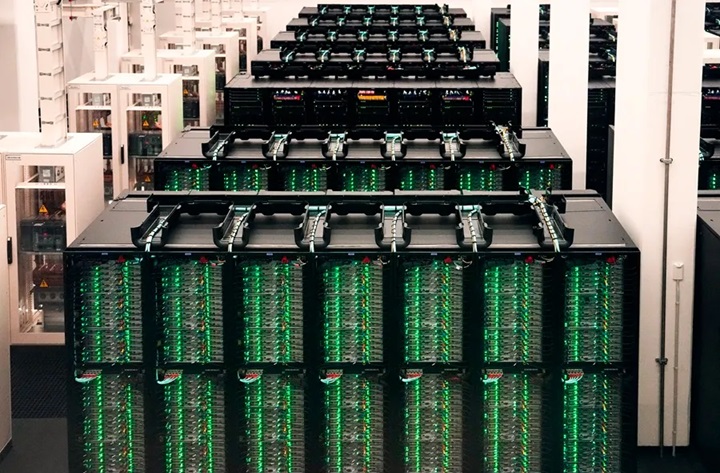

Step into a data hall on a hot afternoon and the first sensation is a kind of manufactured weather. Cold air pours from the floor in a controlled gale, spills around black cabinets that blink like beehives, and exits behind them five or ten degrees warmer. The physics are banal and unforgiving: every watt that feeds a chip must be removed as heat. Do it with evaporative cooling, and you consume water. Do it with air and compressors, and you consume a lot more electricity—much of it still made, in Mexico, with gas and steam.

Scale is what makes the arithmetic feel like a threat. A modest evaporative-cooled facility can use tens of millions of liters of water a year. Querétaro has “scores” of sites, by the state’s own estimate, with dozens more in the pipeline. The counters are real—operators emphasize that plants are not equal. Ascenty says its sites are closed-loop, circulating the same water through chillers rather than venting it into the sky. Microsoft told the BBC its three Querétaro campuses use direct outdoor air for cooling “approximately 95% of the year,” switching to evaporative systems only when the mercury crosses 29.4°C, and reported 40 million liters of water use across those facilities in fiscal 2025. The nuance matters. So does the zoom-out. Google disclosed in its latest sustainability report that total water consumption across its operations rose 28% year over year to roughly 8.1 billion gallons; it stressed that 72% of the freshwater it used came from basins at “low risk of water depletion.” The remainder, by definition, did not.

In Querétaro, the context is harsh. Last year’s drought was the worst in a century. Hills went khaki. Reservoirs showed their bones. In colonias up in the foothills, the afternoon tap ran air. “Private industries are being prioritised in these arid zones,” said Teresa Roldán, an activist in the city’s north, sitting at a kitchen table with a jug of water that arrived by truck, in an interview with the BBC. “We hear that there’s going to be 32 data centres but water is what’s needed for the people, not for these industries. They [the municipality] are prioritising giving the water they have to the private industry. Citizens are not receiving the same quality of the water than the water that the industry is receiving.”

Officials flinch at the accusation. “We have always said and reiterated that the water is for citizen consumption, not for the industry,” a spokesperson for the state government told the BBC, noting that under Mexican law it is the National Water Commission, not municipalities, that issues concessions and volumes. On paper, that is true. In a house where the 6 p.m. pot can’t be filled, it sounds like a footnote. “This is a state that is already facing a crisis that is so complex and doesn’t have enough water for human disposal,” said Claudia Romero Herrara, who founded the water-rights initiative Bajo Tierra Museo del Agua, also speaking to the BBC. “The priority should be water for basic means… that’s what we need to guarantee and then maybe think if there are some resources available for any other economic activity. There has been a conflict of interest on public water policy for the last two decades.”

Transparency, Trust and a Thirsty State

Data centers sell trust by the nine—99.999%—and their secrecy is part of the pitch: physical security, client confidentiality, no surprises. That mindset strains in a drought. Ask ten Querétaro residents how many facilities already hum within the ring road and you’ll get a shrug, a rumor, a number that starts with “scores.” The first step toward coexistence, activists say, is daylight. How many sites? Which basins? How much water, month by month, at the fence line and upstream at the power plant that boils the steam that spins the turbines that feed the megawatts?

That last link is easy to overlook. A campus that uses little or no water on site still has an indirect water footprint if its electricity comes from thermal plants. Mexico’s grid remains dominated by gas. Hydropower contributes but is hostage to rain. Solar and wind are growing fast from a small base. Without honest basin-level accounting—the kind utilities publish for drinking water—Querétaro’s data-center boom looks like a private story written with public ink.

Ren, the UC Riverside professor, added a second variable: air. “The danger of diesel pollutants from data centres has been well recognised,” he told the BBC, pointing to a Washington State Department of Ecology assessment that found troubling air-quality impacts near dense clusters of backup generators. Querétaro plants stack dozens of those engines in tidy rows. They run rarely, by design—as insurance against grid blinks—but when they do, the plumes are real. The fix is not mysterious: stricter emissions controls, stack placement away from neighborhoods, real-time monitoring that anyone can see.

Bravo’s answer is procedural. “We operate under the terms and conditions specified by authorities,” he said to the BBC. It is government’s job, in his telling, to set the rules that protect health and to enforce them “so conditions are acceptable for the communities around.” He is right, and not complete. Efficiency is real—new plants wring more work from every watt than their predecessors. But efficiency is a ratio. If AI models keep getting more compute-hungry—and they have, dramatically—then total consumption can climb even as per-rack numbers fall.

EFE@Enric Fontcuberta

Diesel, Megawatts and the Future on the Line

Every boomtown invents a story to live by. Querétaro’s is elegant: a city can be two places at once. In the morning you eat chilaquiles under the arches. In the afternoon you drive past a campus where a thousand racks hum a thousand miles from the people who will ask a chatbot a question a week from Tuesday. The promise is jobs with insulation from macro shocks—technicians, electricians, security personnel—paid in pesos that stay and circulate. It is prestige without smoke stacks. It is a chance to be a switchboard for the continent.

What the promise becomes will be decided in places far less photogenic than the aqueduct’s overlook: committee rooms where permits are shaped, kitchens where tanker deliveries are logged, substations where utility engineers make the math work in August. There are levers companies can pull now to smooth their welcome. Publish monthly water-use data and power draw at the campus level; fund restoration and recharge upstream; push dry and hybrid cooling even when it costs more in electricity during May and June when reservoirs sag; co-site solar and storage to shave peak demand; install Tier 4 emissions controls on diesel and point those stacks away from schools; wire up monitors that display air and noise data at the fence line in numbers your neighbor can read.

There are levers government must pull. The state can require the disclosure it says it cannot compel. It can put a public dashboard under the aqueduct photo on its website: concessions, withdrawals, basin health, grid stress, generator run hours. It can write a rule that says: when taps sputter at noon in Santa Rosa Jáuregui, every discretionary water user in the basin throttles back or shifts to reuse. It can hold hearings in neighborhood halls rather than hotel ballrooms and make sure the microphones point out as much as in.

Querétaro is not the first place to straddle a paradox, and it won’t be the last. The ironies land harder here because the symbols are so stark. The city’s most beloved piece of infrastructure was built to guarantee growth; the next era of growth may falter if it cannot guarantee the thing the arches once carried. The BBC asked Microsoft and Ascenty to explain their operations; both did, in the language of engineers—dry air, temperature thresholds, closed loops, compliance. Residents spoke in the language of kitchens and buckets. “The priority should be water for basic means,” Romero Herrara said. “Then maybe think if there are some resources available for any other economic activity.”

Also Read: Ecuador’s Amber Windows Rewrite the Story of Flowers, Insects, and Where Life’s Partnerships Began

If Querétaro gets the balance right—if disclosure becomes normal, conservation becomes habit, and smarter engineering bends the extraction curve—the postcard can stay honest in more than one way. Stone arches once carried water to a thirsty city. Fiber and megawatts can, with care, carry prosperity back. The test will not be what the data-center brochures say. It will be whether, at 6 p.m. on a hot day, the tap in a hillside colonia still runs. And whether, when someone looks up from that sink and out at the arches, they feel proud of both the past and the future under them.