Brazil Celebrates Football Cathedral That Still Sends Hearts Airborne at its seventy‑fifth birthday

Seventy‑five years after Rio de Janeiro unveiled the vast bowl locals call the Maracanã, the stadium’s curves, collapses, and comebacks continue to mirror Brazil itself—grand ambitions, painful reckonings, and an unquenchable faith that the next match redeems all.

A Colossus Cast for a Nation in Search of Itself

It began not as a stadium but as a promise—one poured into wet concrete under the August sun of 1948. Brazil was changing fast: new cities were rising, and new myths were forming. The Maracanã was the crown jewel of modernity, a stage to unify a sprawling, racially complex country through the rhythms of football.

As urban historian Christopher Gaffney has argued, the stadium was part of an official effort to “humanize” Brazil’s chaotic modernization, to make nationalism feel less like a decree and more like a shared song. Sociologist Gilberto Freyre had already proclaimed football the clearest expression of Brazil’s multiracial harmony. The Maracanã would give that harmony a home.

On June 16, 1950, Ademir scored its first official goal. Bulldozers still circled the site. Just a month later, the stands were packed to suffocation—199,854 by official count, perhaps more in truth—for the match that would scar Brazil forever. But even in heartbreak, the Maracanã endured as a people’s palace. In the cheap-standing “geral,” steelworkers rubbed shoulders with senators, a fleeting spatial equality rare in Latin American life.

Concrete, Calamity, and the Long Road to Redemption

Over time, the stadium’s arc has never been linear. It has risen, fallen, and rebuilt itself repeatedly—each rebirth marking a different national mood.

After Pelé’s thousandth goal graced its turf in 1969, disaster struck in 1992: a railing gave way during a league final, sending dozens tumbling. Three died. The country grieved, then reimagined. Seats replaced terraces. Accessibility ramps were added. A wastewater system drew praise from UN-Habitat. Each upgrade brought the Maracanã closer to the people—not just a coliseum, but a conscience.

The renovations that prepared the stadium for the 2007 Pan American Games and the 2014 World Cup didn’t just modernize; they symbolized a shift from monumentalism toward accountability. Scholars like Teresa Pires call it the “humanization of infrastructure”—a way to serve, not just stunning.

Even periods of neglect tell a story. Brazilians didn’t look away after the 2016 Olympics when the wiring was looted, and the pitch withered. They asked: What legacy do these mega-events leave? The answer, again and again, has led back to the Maracanã.

Matches That Forged a Legend

FIFA

July 16, 1950 – The Maracanazo

The silence was thunderous. Alcides Ghiggia, almost casually, slipped down the right flank and slotted the ball past Moacyr Barbosa. The scoreboard read Brazil 1, Uruguay 2, but to many, it felt like something more profound had broken. Newspapers the next day read like obituaries. Barbosa, one of the best goalkeepers of his era, was never forgiven.

The Maracanazo wasn’t just a loss—it was a national trauma. And the stadium held it absorbed it and somehow kept welcoming fans back.

September 7, 1963 – The Birth of Torcida Organizada

The score? A forgettable 0–0 between Flamengo and Fluminense. But what happened in the stands changed Brazilian fandom forever. One hundred seventy-seven thousand six hundred fifty-six filled the Maracanã, unleashing synchronized songs, colors, and confetti storms that birthed Brazil’s now-famous fan culture.

Anthropologist José Sérgio Leite Lopes calls it the “humanization of rivalry,” a ritualized performance that turned tension into poetry.

FIFA

November 19, 1969 – Pelé’s 1000th Goal

Santos arrived in Rio de Janeiro, and Brazil held its breath. Vasco da Gama stood in their way in a cup tie, but the opponent felt incidental. What everyone came for—what millions tuned in to see—was a number: 1,000. The Maracanã, already hallowed ground, pulsed with expectancy despite a stubborn tropical rain. Cameras crowded the sidelines. Radio commentators jostled for space. Newspapers had already typeset their front pages. It didn’t feel like a football match—it felt like a coronation.

And then, in the 78th minute, the whistle blew. Under humid skies, Pelé stepped up to a penalty spot with the weight of history on his shoulders. His shot beat goalkeeper Andrada, and the game stopped—for 25 minutes.

He grabbed a mic and implored: “Help the children.” It was a moon landing of the soul for Brazil and the global South.

July 12, 1989 – Brazil vs. Argentina, Copa América

Bebeto’s scissor-kick. Romário’s instinctive finish. A 2–0 win over Argentina that ended four decades of Copa América frustration. Police and fans hugged in the streets. The boundaries of daily life dissolved just for a night.

The Football Heritage Association

September 19, 1993 – Romário’s Redemption

Banished for indiscipline, Romário was only recalled to the national team out of desperation. Brazil needed to beat Uruguay to qualify for the 1994 World Cup, and he scored both goals.

Coach Carlos Alberto Parreira called it a “metabolizing of conflict into art.” The Maracanã agreed.

July 13, 2014 – Germany’s Triumph, Brazil’s Grace

Brazil was still reeling from the 7–1 loss to Germany days earlier in Belo Horizonte, so the Maracanã hosted the World Cup final. Mario Götze’s volley gave Germany the trophy, but the event showed Brazil’s capacity to host, heal, and hold the world even when its heart was broken.

FIFA

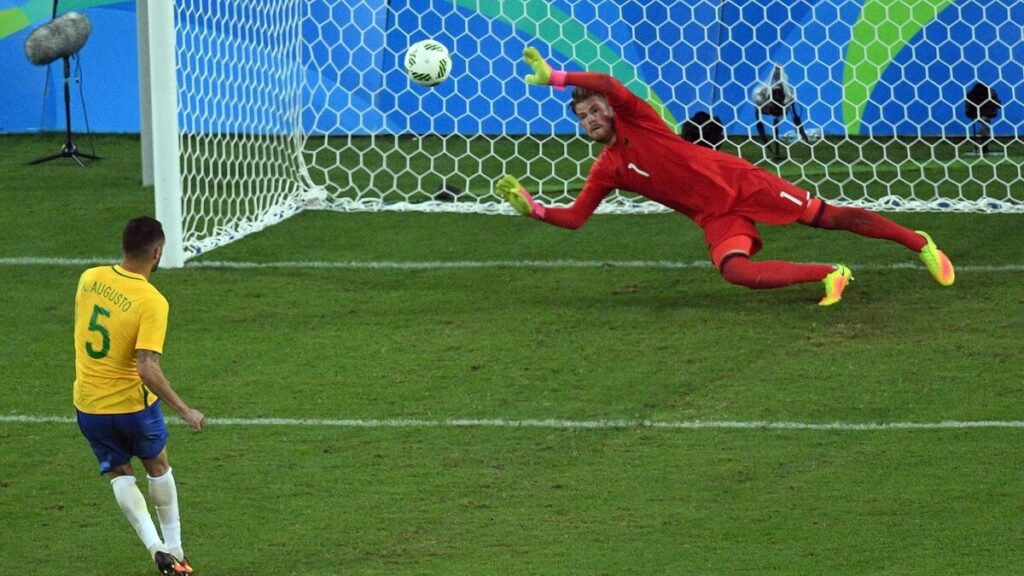

August 20, 2016 – Neymar’s Tears

Another final. Another Germany matchup. Neymar’s free-kick, the equalizer, then the final penalty—his final act before collapsing in tears on the ground where Barbosa had once fallen.

The Olympic gold didn’t erase 1950, and it didn’t erase 2014. But it transformed something. Across Latin América, the media called it a “re-humanization” of Brazil’s football soul.

FIFA

Seventy-Five and Still Singing Toward Tomorrow

The Maracanã isn’t done—not even close.

The Flamengo-Fluminense consortium, in partnership with Rio’s state government, plans to crown the stadium with solar panels and 5G nodes, turning it into a beacon of sustainability and digital connectivity. Environmental economists from the Federal University of Rio estimate this could offset 620 tons of CO₂ annually—proof that even legends can go green.

The Brazilian Football Confederation has submitted the Maracanã for the 2027 Women’s World Cup final. If selected, it will become the first stadium in history to host championship matches for both men’s and women’s tournaments. At last, the temple of Brazilian football would speak in two registers of glory.

Yet, for all the tech and planning, the stadium’s fate depends on more human choices. Will it continue to allow cross-class mingling, or will gentrification push low-income people to the margins again? Will public transport be upgraded so every fan can arrive—and leave—without indignity?

Urbanists argue that what’s at stake is more than football. It’s democracy, memory, and a city’s soul.

Also Read: River Plate’s Argentinean Gems Powering Real Madrid’s Golden Eras

For now, the old giant still breathes—with drums, chants, and trembling concrete that holds seven and a half decades of ecstasy and anguish. From Ghiggia’s dagger to Neymar’s redemption, from Pelé’s voice to confetti wars in the stands, the Maracanã is not just a structure. It’s a feeling, a place where millions have been made to feel unmistakably, intimately alive.

And that, perhaps, is the secret of its undiminished spell.