Mexico Prepares World Cup Welcome with Football Memory Diversity Pride

With Mexico as the guest country at FITUR Madrid, football becomes a language and a promise. As the 2026 World Cup approaches, Mexican cities present the tournament not just as a spectacle, but also as civic memory, a tourism strategy, and a statement about openness in a divided world.

Mexico Turns Tourism Stands into World Cup Stages

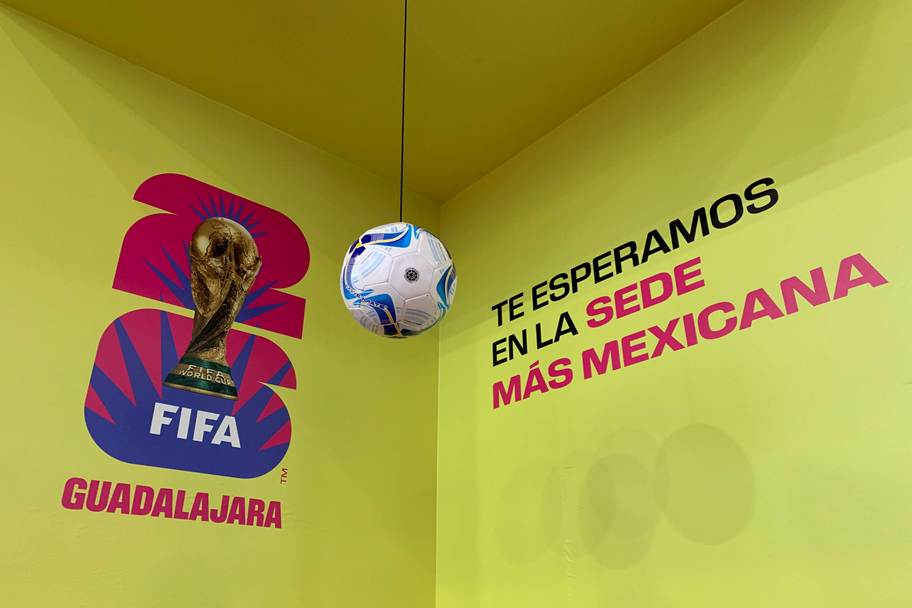

Football dominates the Mexican presence at the Forty-sixth International Tourism Fair (FITUR) in Madrid, where Mexico arrives not just as a participant but as the guest country of honor. Bright, oversized stands foreground the sport with an intensity unmatched by its co-hosts. While the United States and Canada keep their booths modest and largely silent about the tournament, Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey turn football into architecture.

In the Mexican pavilion, the name Jalisco—the state that hosts Guadalajara—is spelled out with dozens of miniature footballs. Scale models of stadiums sit beside scarves adorned with the golden FIFA World Cup trophy, while a small goal invites passersby to take a shot. The message is tactile and deliberate: football here is not a backdrop but a shared ritual. It is felt in the design, in the invitation to play, and in the unapologetic pride of hosting thirteen of the one hundred forty-four matches of the 2026 World Cup, which will run from June eleven to July nineteen.

That emphasis contrasts sharply with the other hosts’ relative restraint. Although most matches will be played north of the Mexican border, the visual and narrative center of gravity at FITUR leans south. Mexico’s stand is larger, louder, and more confident—less about logistics, more about belonging. It reflects a long-standing relationship between the country and the World Cup, one rooted in memory rather than novelty.

Mexico City Frames Football as Civic Memory

The countdown is already public. In 139 days, on June eleven, the opening match of the 2026 World Cup will be played in Mexico City, where Mexico faces South Africa. The final will come weeks later in New York, but the symbolic starting point is unmistakably Mexican.

Preparing for that moment, Mexico City, a metropolis of twenty-three million inhabitants, has embarked on an overhaul that blends infrastructure with symbolism. Authorities report eight hundred public works projects, the installation of 30,000 street surveillance cameras, and hospitality training for 500,000 people. The scale signals that this is not merely a sporting event but a citywide mobilization.

“Queremos compartir al mundo el ambiente mundialista que se va a vivir en la Ciudad de México, y por eso decimos ‘la pelota vuelve a casa’,” said Alejandra Frausto, Secretary of Tourism of Mexico City, framing the tournament as a homecoming rather than a hosting duty, she told EFE.

That phrase—the ball returns home—draws from history. Mexico City will become the only city in the world to host World Cup matches for a fourth time, according to local authorities. The officially recognized tournaments are nineteen seventy and nineteen eighty-six, but Frausto insists the story is broader. “Hay otro de mil novecientos setenta y uno que no está reconocido oficialmente por FIFA. Es un mundial femenino y México quedó subcampeón,” she added, invoking the nineteen seventy-one Women’s World Cup, an event often marginalized in official football histories, she told EFE.

That insistence on remembering the unrecognized is telling. It aligns with a Latin American approach to global events—participation paired with critique, celebration tempered by historical correction. For Mexico City, the World Cup will spill far beyond stadium walls. All 104 matches will be shown free at public football festivals. A massive football-themed parade will take place in June, while March will feature what officials call “the largest football class in the world.” On May thirty-one, the city plans a sixteen-kilometer human wave, a choreographed gesture of collective anticipation.

“Vamos a hacer una ola de dieciséis kilómetros… ya habrá parte de este ambiente mundialista,” Frausto said, inviting visitors to arrive early and witness the city warming up in unison, she told EFE.

Mexico Sees Football as Tourism and Inclusion

Beyond celebration, city officials frame the tournament as an economic and cultural opportunity. Mexico City wants football fans to stay, wander, and return. The pitch is expansive: museums—”somos la ciudad con más museos en el mundo,” Frausto noted—historic neighborhoods, and thematic routes such as those tracing the life of Frida Kahlo, one of the capital’s most internationally recognized figures, she told EFE.

The ambition extends outward, encouraging visitors to explore neighboring states, dispersing tourism income, and rebalancing the concentration that mega-events often produce. “Estamos convencidos de que las personas que vengan se van a convertir en nuestros embajadores y volverán… con sus familias,” Frausto said, emphasizing repeat travel over one-time spectacle, she told EFE.

There is also a social dimension that Mexican officials foreground more openly than many host cities. The 2026 World Cup will unfold during LGTBIQ+ Pride Month, and Mexico City intends to lean into that overlap rather than sidestep it. “Vamos a celebrar… la diversidad. Para nosotros la diversidad es la mayor riqueza de la humanidad,” Frausto said, acknowledging that football culture can often feel rigidly binary and exclusionary, she told EFE.

The capital’s message is explicit: it does not matter where a team plays. In Mexico City, all cultures and nationalities are welcome, “sin discriminación, sin racismo, sin ningún tipo de xenofobia,” she insisted, she told EFE.

At FITUR, that stance is not delivered as a slogan but embedded in a presentation. Football is used as an entry point to talk about history, gender, rights, and openness—an approach deeply rooted in Latin American traditions of using mass culture to negotiate social meaning. In a global tournament shared with wealthier neighbors, Mexico positions itself not as the biggest host, but as the most narratively intentional one: a country that treats football as memory, hospitality as policy, and diversity as a competitive advantage rather than a footnote.

Also Read: Argentine Fans Chase 2026 Dreams, Wallets, and One More Star