Brazil swings to the right, setting the stage for a Trump-like leader

In a big, multiethnic country built by immigrants and slaves, a septuagenarian white male leader is riding a right-wing backlash after an era of leftist rule. His much-younger spouse is a former model. His five-letter last name starts with a “T” — but it’s Temer, not Trump.

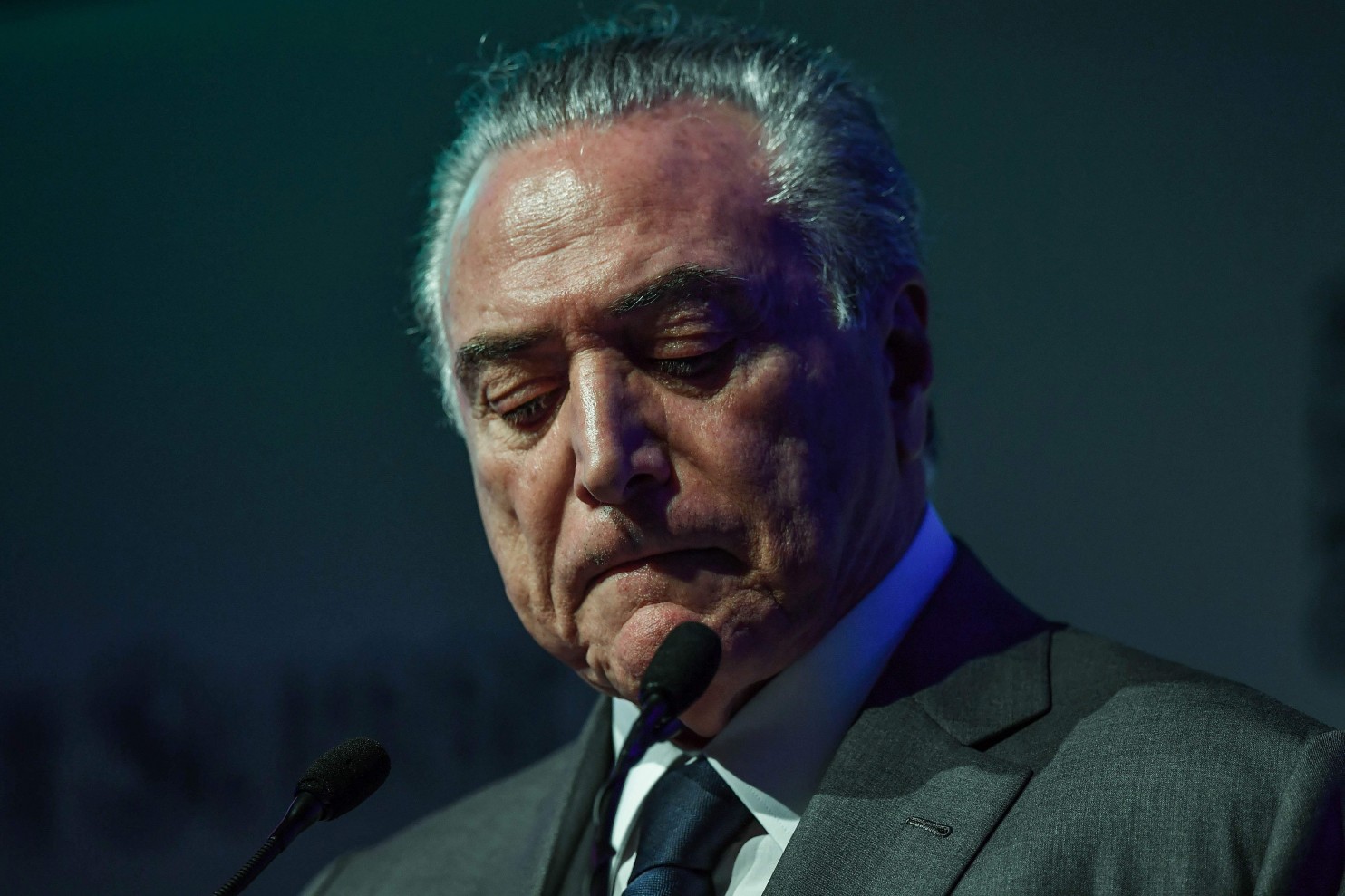

Brazilian President Michel Temer took office five months ago after the impeachment and political humiliation of the country’s first female political leader, Dilma Rousseff, ousting her left-wing Workers’ Party after 14 years in power. Temer named an all-male cabinet and quickly embraced a right-leaning, regulation-slashing agenda.

Temer, 76, is not a Brazilian version of Trump. He does not have a populist touch or a showman’s flair. He is a career politician and government insider at a time when both things are deeply unpopular in Brazil.

And yet, like the United States, Brazil is a big country whose political center has swung abruptly to the right. The next presidential election is not until 2018, but in municipal-level contests held in October, Rousseff’s once-dominant Workers’ Party was trounced, losing 60 percent of the city government seats it controlled. Temer’s centrist Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) and the more conservative Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) swept the country’s most important districts.

The results were the clearest signal yet of a “shift in mentality” in the country, according to political analyst Lucas de Aragão of the Brasilia-based consulting firm Arko.

“It’s an anti-status-quo sentiment, just like Brexit and Trump,” Aragão said, “but I don’t think it’s about ideology as much as a lack of results.”

Rousseff was impeached on charges of violating budget-making rules, not for personal corruption. But she and the Workers’ Party have shouldered most of the blame for Brazil’s worst economic crisis since the 1930s and the biggest corruption scandal in the country’s history.

Temer, who is married to a 33-year-old former model, is a constitutional law expert who speaks carefully and sends out dull, dutiful tweets. His patrician bearing may be hurting him at a time when Brazilians are looking for someone who doesn’t talk like a professor. And with virtually Brazil’s entire political establishment under suspicion of shady dealings, Temer’s tight-lipped rectitude can seem like opacity.

Once in power, Temer embraced Brazil’s rightward turn, but it has not embraced him. His approval ratings hover around 14 percent, roughly on par with Rousseff’s before her impeachment.

More than half the country sees Temer as dishonest, according to a December survey by Datafolha, Brazil’s main polling firm. His low approval ratings are a sign that he has not benefited from Brazil’s shifting political winds, even as he tries to tries to tack with them.

“He gives the impression of a very traditional politician, who is rarely seen on the streets,” said Mauro Paulino, director of Datafolha.

Much of Brazil’s political and business elite, including Temer, is under the cloud of the sprawling corruption investigation known as “Car Wash” that has uncovered $2 billion in illegal bribes over the past three years. The former speaker of Brazil’s Congress has been imprisoned, along with some of the country’s most powerful business executives.

According to leaked plea bargain testimony, a jailed former construction executive has accused Temer of soliciting nearly $3 million in illegal campaign funds. Temer has not been charged, and he has repeatedly insisted that he supports the investigation and has nothing to hide. After the Supreme Court judge overseeing the Car Wash probe died in a plane crash last month, Temer said he would wait to nominate a replacement until the judge’s colleagues — not him — could decide who would take over the case.

It may be too late for Temer to recover his credibility. With less than two years left in his term, Brazil seems to be waiting for its Trump to come along. Populist outsiders such as the new mayor of Sao Paulo, a business tycoon who starred on the Brazilian version of “Celebrity Apprentice,” are often mentioned among the early favorites for 2018.

What many Brazilians and Brazilian lawmakers have embraced is Temer’s right-leaning austerity agenda. He has won approval in Congress for a 20-year freeze on social spending and his refusal to bail out state governments that have blown their budgets. He has eased restrictions on foreign oil companies looking to drill for lucrative offshore deposits, and he is expected to present new legislation to open up Brazilian agribusiness and the airline industry to full foreign ownership.

Although Temer has stopped the economic slide, the country’s jobless rate remains in the double digits, and 2017 growth is projected to be just 1 percent.

“People are not consuming, because they’re afraid of losing their jobs,” said Paulo Sotero, the director of the Brazil Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington.

“Temer’s job is to calm people down, take measures that are effective, and put Brazil back on a sustainable growth pattern,” Sotero said. “It’s probably too much for his government to accomplish by 2018, but he can start working on it, and he has.”

Unlike Trump, Temer is not overly concerned with his popularity, analysts say. He insists he will not be a candidate in 2018. He has his eye on his long-term legacy, and whether he will be remembered as a leader who restored stability and lifted Brazil out of the ditch.

“This is a country that changes opinion very quickly,” said Aragão, the political analyst. “Don’t forget Rousseff had the highest approval rating of any president in history” at the beginning of her first term.

Temer’s presidency has signaled a shift in priorities for Brazil, from the multiculturalism and inclusive social message of his leftist predecessors to a more singular focus on economic liberalization. Some of those changes have fueled large street protests, and “Fora Temer” (Temer out) graffiti is a frequent sight in major cities.

Temer came under fire days after his inauguration for not appointing a single woman or Afro-Brazilian to his 23-member cabinet. He eventually appointed women to head the attorney general’s office and the central bank, but the damage was done.

To cap it off, anger over the perceived slight to women was compounded by the fact that Temer got his job by replacing the country’s first female president, with his party driving the impeachment proceedings.

“The lack of sufficient female representation in his government feels like a huge step backwards,” said Rosiska Darcy, a feminist author and political critic. Rousseff had appointed 14 women to cabinet-level positions. “We are half of Brazil’s population,” Darcy said.

The global shift to the right poses a threat to the gains of Brazil’s feminist movement, she added, saying that Brazilians should draw inspiration from the U.S. women’s march that followed Trump’s inauguration.

“The Americans spoke of resistance,” said Darcy. “We have to fight this wave of conservatism.”