Brazil’s Bloody Mirror: The PCC, the CV, and a War the State Keeps Losing

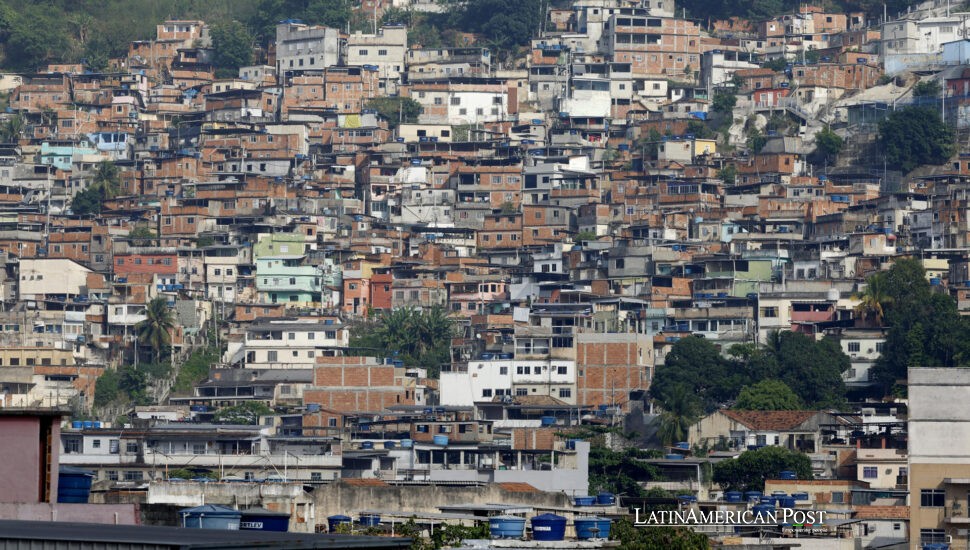

After a Rio favela operation left between 121 and 132 alleged criminals dead, Brazil has been forced to stare into a mirror it long avoided. The reflection is grim: the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and Comando Vermelho (CV) now operate less like street gangs and more like multinationals of crime, exporting violence, laundering profits, and governing neighborhoods where the state shows up only in bulletproof vests. The siege may have ended, but what it revealed is still burning—a country where the firefight has become policy, and policy has forgotten purpose.

Two Acronyms, One Uncomfortable Mirror

Brazil’s underworld speaks in initials. PCC and CV—born behind bars—now shape the rhythm of violence from São Paulo to the Amazon delta. The recent massacre in a Rio favela complex didn’t weaken their empires; it exposed the illusion that body counts equal strategy.

The Brazilian Forum on Public Safety counts eighty-eight criminal factions across the country. Inside that chaos, two stand above the rest—PCC and CV—controlling drug routes, black markets, and a workforce of despair. Organized crime has significantly developed and is the primary security challenge in Brazil. PCC and CV are present in nearly the entire country,” said David Marques, a coordinator at the Forum, speaking to EFE.

The PCC’s ascent reads like the biography of a failed prison system. It was founded in 1993 inside a São Paulo penitentiary—initially a prisoners’ union fighting inhumane conditions. Within a few years, it became a bureaucracy of survival, complete with internal statutes and a chain of command. Thirty years later, prosecutors describe a transnational corporation of crime, with operations stretching into Paraguay and Bolivia and an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 members inside Brazil. Its leader, Marcos Willians Herbas Camacho—”Marcola”—remains behind bars in a maximum-security facility, but his orders move freely through a communications network the state still hasn’t cracked.

When a prison-born faction becomes a continental conglomerate, the problem isn’t just crime—it’s governance.

The Franchise Spreading Through the Amazon

The CV’s roots reach further back, to the 1970s, when inmates in Rio’s prisons fused political ideals with bandit rebellion under the dictatorship. Over time, the Comando Vermelho evolved into a decentralized franchise: each cell a local dealership of terror, connected by ideology, graffiti, and shared profit.

Unlike the PCC’s tight hierarchy, CV is porous—a red tide of neighborhood bosses and micro-fiefdoms. It thrives where institutions are weakest. Since 2017, its reach has surged across the Amazon and the impoverished northeast, carving out drug and weapon corridors in territories the government barely maps.

In Belém, host city for the upcoming COP30 climate summit, CV’s presence is visible on every streetlight—red letters spray-painted on walls announcing rules of conduct: “No stealing in the community.” It’s not benevolence; it’s branding. Behind the slogans stand rifles, extortion rackets, and local “courts” that decide disputes faster than the judiciary ever could.

As Marques told EFE, “The CV’s ability to adapt to each neighborhood is what makes it so dangerous.” He’s right. A gang that learns a city’s slang before its police do isn’t just surviving; it’s governing.

And yet the state’s answer remains painfully predictable: operations, raids, funerals, silence. Each assault may reclaim a street, but the business model stays untouched. In Rio, the gangs monopolize essentials—gas, internet, cable, transport. In the Amazon, they control supply chains faster than the state can issue warrants. The logic of “shoot, report, repeat” hasn’t just failed—it has industrialized futility.

Prisons, Poverty, and the Endless Recruitment Pipeline

To understand how these gangs regenerate, walk into any Brazilian prison. Seven hundred five thousand inmates occupy space built for half that number. Overcrowded, underfed, and brutal, these facilities are less correctional than recruitment centers. New detainees are sorted by gang allegiance for survival; refusing affiliation can mean death.

Inside, the bosses issue orders through lawyers, family networks, or smuggled phones. The concrete walls don’t stop the commands—they distribute them.

Every overcrowded cell is a lesson in state abandonment. It’s no coincidence that both PCC and CV emerged from within the same carceral collapse. When incarceration becomes the poor man’s welfare system, and police raids substitute for social policy, gangs become the closest thing many Brazilians have to governance.

None of these excuses their cruelty. But it explains why firefights can’t outgun poverty. In favelas and rural towns alike, residents face a brutal choice: the extortionist who keeps the lights on or the government that arrives only in armored trucks and disappears by nightfall.

Suppose Brazil wants to stop burying the same teenagers year after year. In that case, it must break the recruitment chain: education, clinics, jobs, and a justice system that treats pretrial detention as a last resort, not a reflex. Empty the prisons of petty offenders and you weaken the cartels’ labor pool.

Follow the Money, Not Just the Guns

The men with rifles are replaceable. The men with spreadsheets are not. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva calls PCC and CV “multinationals of crime,” and evidence supports him. Investigators have uncovered laundering networks hidden inside bus companies, motels, gas stations, real estate, and even fintech startups. One police report detailed a ring washing profits through a chain of stuffed-animal stores—a grotesque metaphor for Brazil’s blurred lines between legality and crime.

The CV’s operations are cruder but equally lucrative. It taxes everything that moves inside its turf—commerce, utilities, even love hotels—turning control into perpetual income. “They don’t seek to seize power or launch revolutions,” sociologist Ignacio Cano of Rio State University told EFE. “They want profit, and they achieve it by corrupting the state.“

If the goal is to dismantle these empires, the state must follow their accountants, not just their gunmen—audit municipal contracts. Track suspicious fintech flows. Target the lawyers and bankers who launder blood money into legitimate business portfolios. Pair every police raid with financial forensics—and when the shooting stops, flood the vacuum with civilian life.

That means social workers, teachers, tax inspectors, small-loan officers, and public defenders walking the same streets the commandos once did. Security begins when normalcy returns.

Brazil’s dilemma is no longer who controls the streets but who defines order. The PCC and CV won’t collapse under the weight of another operation. They’ll fall only when the state learns to act with the same patience and structure that its enemies have mastered for decades.

The Rio massacre wasn’t a victory—it was déjà vu. The real test begins the day after the raid, when the armored trucks leave and the extortionist knocks again. Only then will Brazil decide whether it intends to govern its neighborhoods or merely avenge them.

Also Read: Rio’s Long Night: Inside Brazil’s Deadliest Police Raid and a Favela Left to Bury Its Own