Carandiru Still haunts Brazil and its Prisons Keep Breeding the Same Violence

More than three decades after São Paulo’s Carandiru massacre left 111 inmates dead in half an hour, Brazil’s jails remain the world’s most overcrowded. Survivors, jurists, and former guards say the bloodied echoes of 1992 still thunder through today’s crumbling cellblocks.

A “Model” Prison Turns into a Powder Keg

When the São Paulo House of Detention opened in 1956, reporters raved about sewing workshops, a fully staffed infirmary, and expansive courtyards where inmates would play football under royal palm shade. By 1992, that modern showcase had rotted into Carandiru, a vast concrete hive crammed with 8,000 men—more than twice its intended capacity. Sewage geysers from cracked pipes and water ran only a few hours daily. The corridors stank of sweat, bleach, and fear.

Guards, outnumbered forty to one, surrendered absolute authority to rival gangs. Knives fashioned from bed frames were currency; HIV spread so fast that researchers recorded infection rates above 20 percent, higher than any prison in Latin America. Dr Drauzio Varella, the cancer specialist who volunteered there, later wrote: “Carandiru was a city the government had abandoned. Everyone sensed the next explosion.”

State lawmakers toured the cells after a 1989 riot that left seven dead. Cameras captured their horrified faces; promises of reform filled the evening news. Nothing changed. The gangs stocked more shivs, and military police polished their M-16s.

October 1992: Fifteen Minutes, 111 Corpses

Friday, October 2, 1992, began with a routine squabble on Pavilion 9’s soccer pitch. A fist flew, a handmade blade flashed, and guards slammed iron gates before sprinting to radios. Governor Luiz Antônio Fleury Filho authorized the elite Rondas Ostensivas Tobias de Aguiar (ROTA) to retake the block “by whatever means necessary.”

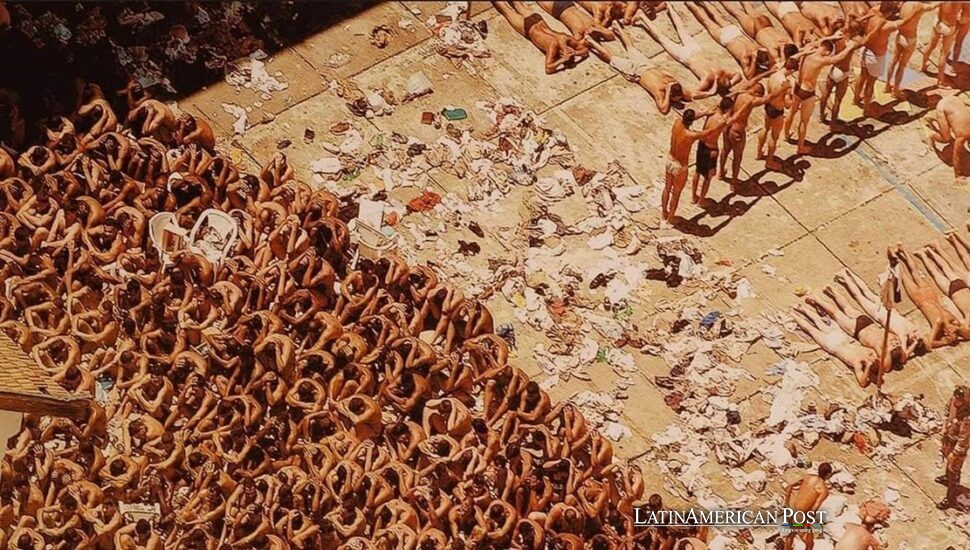

According to witness statements later gathered by Human Rights Watch, negotiations were mostly perfunctory- ten minutes. At 3:40 P.M., police hurled tear gas canisters through window grates and stormed stairwells. Gunfire echoed down echoing corridors; inmates waving shirts in surrender were shot point-blank. A medic with the state forensic institute later testified that 73 of the dead were killed by head or chest wounds fired at close range. Not a single officer died.

Newspapers the next morning splashed front pages with grisly photographs: bodies piled like timber, walls painted scarlet halfway to the ceiling. President Itamar Franco called the scene “a stain on the republic.” Amnesty International said the slaughter “bordered on genocide.”

Inside the prison hospital, Varella stitched survivors who whispered the same word: china—massacre. One man, abdomen perforated by three bullets, grabbed the doctor’s coat and gasped, “Tell them we had our hands up.”

Trials, Acquittals, and an Endless Appeal Loop

Public outrage forced prosecutors to act. Colonel Ubiratan Guimarães, the operation’s field commander, was convicted in 2001 of 102 homicides and sentenced to 632 years. A higher court overturned the verdict two years later, arguing the jury had disregarded “orders under chaotic conditions.” Guimarães celebrated the reversal by running for state assembly—and won. He was shot dead in 2006, an assassination that was never solved.

Most of the rank-and-file officers skated for two decades. Only in 2013, after Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that collective responsibility could apply to police platoons, did trials resume. Seventy-four members of ROTA received sentences as high as 624 years. In 2021, the Superior Court of Justice annulled every conviction on a procedural technicality, enraging relatives who had attended hearings for eight straight years. Federal prosecutors are now chasing a retrial under Brazil’s “perpetual crime” doctrine for egregious human rights violations; no date has been set.

Maria dos Santos, whose brother José Carlos died with three bullets in his back, keeps newspaper clippings in a plastic bag. “Each time a judge cancels the case,” she told a reporter, “they kill my brother again.”

From Ruins to Parkland, Yet Old Demons Survive

Carandiru’s walls fell in 2002. Today, joggers circle Youth Park, unaware they stride over foundations once slick with blood. Only one pavilion stands, a prison museum where tourists gawk at dented riot shields and toothbrush shanks.

Outside São Paulo, the system has only swelled. Brazil’s inmate population now tops 830,000 people in facilities built for half that number, according to the National Justice Council. Tuberculosis rips through barred dormitories at 35 times the national infection rate. Guards still barter with gang bosses to keep a tenuous peace; two cartels born in Carandiru’s courtyards—the Primeiro Comando da Capital and the Comando Vermelho—now control drug routes from the Amazon to Paraguay.

Riots recur with a sickening rhythm. In 2017, a gang war in Amazonas state left 56 prisoners dead, many decapitated. In 2023, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ordered Brazil to compensate Carandiru survivors and overhaul prisons nationwide, calling the massacre “an emblematic case of lethal state violence.” Compensation remains unpaid; reform bills collect dust in Congress, where a tough-on-crime caucus shouts down any budget for rehabilitation programs.

Each October 2, families gather outside Youth Park, lighting 111 candles against the chain-link fence. Office workers jog past—some stop, most don’t. “My brother’s grave isn’t only in the cemetery,” Maria says, tracing José Carlos’s name on a plywood cross. “It’s in every overcrowded cell the state still refuses to fix.”

Also Read: Colombia Treasure Hunt Deepens As San José Coins Reveal Lima Origin

For a few minutes, the park is silent, and the city’s roar is held at bay by candlelight and memory. Then phones buzz with the news: another riot in Rio Grande do Norte, dozens injured. The candles flicker in a breeze that smells faintly of eucalyptus and something older—gunpowder, perhaps, or the copper scent of blood never thoroughly washed from the concrete below.