Chile Revisits Women’s Underground Network Defying Brutal Dictatorship

When Augusto Pinochet’s tanks ended democracy on September 11, 1973, thousands of Chilean women slipped behind the junta’s back—hiding fugitives in prams, smuggling rifles inside birthday cakes. They enter the light fifty years later, determined that history will finally say their names.

A Housewife’s Kitchen Becomes a Guerrilla Dispatch Center

Mónica Urrutia still keeps her grandmother’s walnut dining table, but today, it sits inside the Museum of Memory and Human Rights, scarred by cigarette burns and an unexplained bullet groove. In 1974, that tabletop was the command post for Óscar Guillermo Garretón, a socialist leader hunted so relentlessly that DINA agents once showed his photograph to kindergarten classes. Mónica, then twenty-three, greeted him with a pot of lentils and a promise: “Mi casa es tu trinchera.”

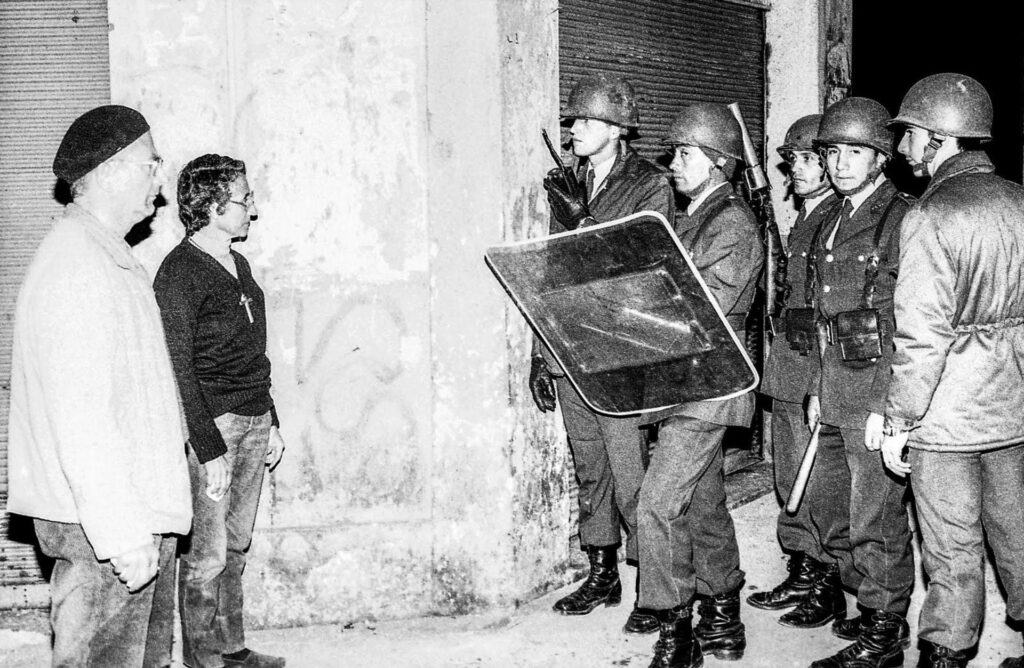

While Garretón plotted escape, Mónica’s neighbors saw only the routine of a middle-class Santiago wife—washing cloth diapers, hanging sheets, chauffeuring her toddler to catechism. That camouflage was deliberate. Declassified DINA manuals inserted into court files in 2005 show agents rated “amas de casa” (housewives) as “low operational threat.” The dictatorship never understood that Chile’s domestic spaces had become the opposition’s safest trenches.

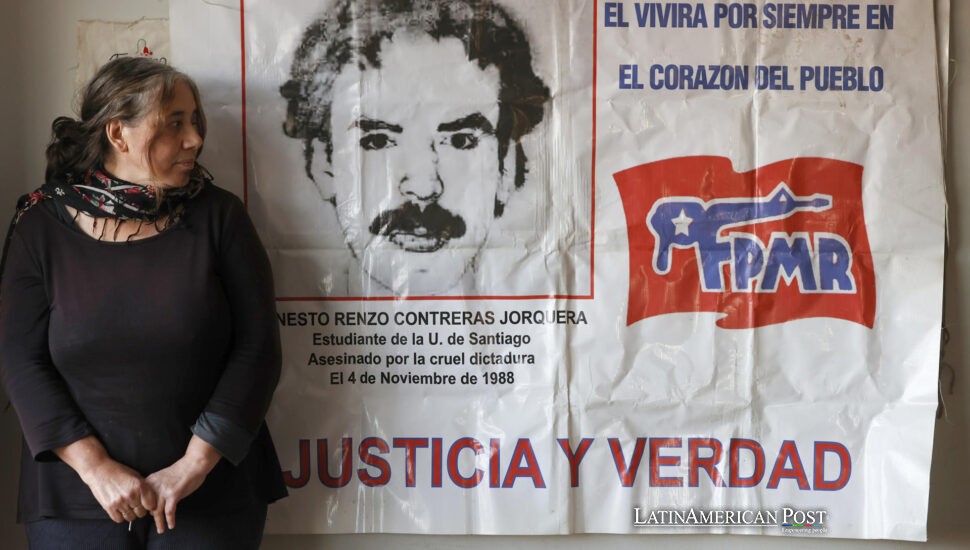

Across town, university drop-out Claudia R. stitched a padded baby blanket that hid the buttstock of a Belgian FN rifle. At a checkpoint in Ñuñoa, soldiers rummaged through her groceries, found jars of puréed peaches, and waved her on. Minutes later, the weapon lay under a crib in Villa Liberation, ready for an FPMR ambush. “They saw a woman with formula and thought I was harmless,” Claudia laughs, rolling up a sleeve to reveal lattice scars from electric cables. “That mistake kept companions alive.”

Sister María Inés and the Neonatal Getaway

Religion teacher Sister María Inés Urrutia was grading essays at Colegio San Ignacio when the phone trembled off its hook. A Jesuit doctor at a public maternity ward whispered that DINA men were coming for a young mother who had named her newborn Salvador. If the nuns could not spirit the pair out, both would disappear before nightfall.

María Inés slipped into a taxi with a spare habit and baptismal shawl. Minutes later, she threaded hospital corridors where orderlies pretended not to see. She swaddled the baby, tucked him under her robes, and led the mother down a stairwell flooded with iodine smell. Security logs unearthed by journalist Patricia Verdugo confirm that DINA squads arrived thirty minutes after the nun’s departure—too late. Today, Salvador lives in Montreal. He calls once a month; she still trembles at the ringtone.

“When people ask where I found courage,” she tells EFE, rosary swinging, “I answer with another question: How could I have slept if I had left them there?” The nun’s rescue became legend inside underground cells, proof that faith could wield sharper steel than any rifle.

Dictatorship Myth-Making Meets the Women’s Quiet Revolt

Pinochet’s regime cultivated an image of martial order: marching bands, ration-book lines, the president in Ray-Ban glasses proclaiming that Chile had been “saved from Marxism.” Behind that façade, women’s networks punched holes in the narrative. They forged hundreds of passports inside parish offices, where typewriters clacked while choirs rehearsed in adjoining rooms. They ferried microfilm inside crochet balls to embassies willing to smuggle diplomats’ pouches out of the country.

One courier, Patricia Vásquez, used her job as a flight attendant on LAN-Chile to smuggle an 8-millimeter film of torture bruises shot secretly at the morgue. The reel reached Stockholm, where Amnesty International screened it for diplomats hours before the UN Human Rights Commission voted on Chile’s record. The regime’s ambassador sputtered that the footage was communist fakery; the bruises said otherwise. “That tiny cassette weighed more than a suitcase,” Patricia recalls, her knuckles whitening at the memory of customs officers strolling the aisle.

Yet when democracy returned in 1990, televised commemorations featured mostly male heroes—the party leaders, the militant poets, the exiled senators. The women watched the podiums, their stories still smothered by the very invisibility that had once kept them safe.

An Uneasy Reckoning Half a Century Later

President Gabriel Boric marked last year’s coup anniversary by announcing a National Memory System: DNA banks for unidentified remains, digitized archives, and an oral history drive focused on “the unrecognized architects of resistance.” For the first time, invitations went straight to women like Mónica, Claudia, and Sister María Inés.

But commemoration is a minefield. A July Cadem poll found 21 percent of Chileans still call the 1973 coup ‘necessary.’ Ultra-conservative deputies argue the new project “weaponizes history,” and business leaders balk at funding museums while the peso wobbles. “Memory is expensive; amnesia is cheap,” sighs anthropologist Claudia Dides, who curated the inaugural exhibit “Las que tejieron la fuga” (“Those Who Knitted the Escape”). Outside Santiago, graffiti sneers “Boric mentiroso” over a mural of the women couriers.

Inside Londres 38, survivors guide schoolchildren past the “parrilla”—an iron bed where prisoners were electrocuted. The hallway ends at a blank wall awaiting a new bronze plaque. The draft text, circulating among relatives for approval, lists 47 names—all women.

One afternoon in April, the nuns of Colegio San Ignacio rang the courtyard bell and handed Sister María Inés a gray envelope. Inside lay two objects: a faded photo of a baby swaddled in a baptism shawl and a note in French. “I live free because you did not hesitate,” it reads, signed simply “Salvador.” Her hands shook as she pressed the picture to her chest.

Mónica keeps a different relic: Colonel Guimarães’s overturned conviction notice, framed beside her grandmother’s walnut table. She points to the bullet groove, a reminder that justice remains unfinished. “They erased our footprints once,” she tells visiting students. “Our job now is to step so loudly they can never erase them again.”

Also Read: Latin American’s Sleepless Nights During L.A. Immigration Raid Terror

Credits: survivor testimonies to EFE; archival details from Universidad Diego Portales, Human Rights Watch, and National Memory System documents.