Cuba’s Shadow Soldiers: How Havana’s Fighters in Ukraine Threaten the Americas

The revelation that at least 4,200 Cuban nationals are fighting for Russia in Ukraine isn’t just a battlefield curiosity—it’s a geopolitical tremor. Behind the numbers lie deeper questions: Who allowed them to go? What happens when they come back? And how far will Havana go to revive its old alliance with Moscow while courting favor in the new world order?

Havana’s New Old Game

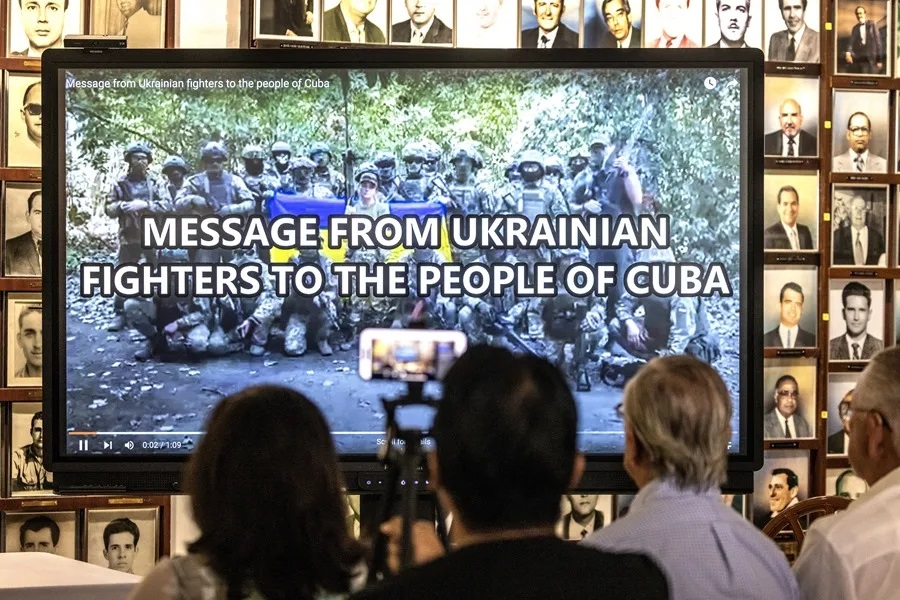

The figure itself stuns. Ukrainian intelligence officials told The New York Post that more than 4,200 Cubans are serving in Russian ranks. Even in a war thick with mercenaries and imported manpower, the image of Cubans in Donetsk trenches triggers Cold War flashbacks—Havana once again fighting for Moscow’s cause.

Russia’s manpower crisis has been visible for months. But recruiting from Cuba feels like déjà vu wrapped in desperation. Moscow gets cannon fodder; Havana gets currency, fuel, and leverage. The men, according to the Cuban government, are “volunteers.” But few believe that. Cuba controls its citizens’ movement with one of the most restrictive exit systems in the world. The idea that thousands slipped off the island unnoticed strains credibility.

“4,200 Cuban mercenaries are not a small number by any means, and it’s unlikely that the Cuban government wouldn’t know about it,” said Alex Plitsas, a fellow at the Atlantic Council, in comments to The New York Post. He called it a “backwards step”—a slide back toward Cold War complicity with “war criminals and terrorists.”

For Washington, the signal is unmistakable. “Yet another example of authoritarian regimes in Latin America actively siding with America’s enemies,” a source close to the White House told The New York Post.

The pattern is familiar. During the Cold War, Cuba sent troops to Angola, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua—proxy wars that let Havana project power without owning the consequences. This time, ideology has been replaced by transaction. What’s for sale is manpower.

What 4,200 Fighters Really Signal

For Russia, the logic is simple: fill the trenches without angering Moscow’s elites. Cuban recruits provide bodies that keep Russian mothers quiet. But what matters most isn’t the immediate military gain—it’s the signal of allegiance.

If Belarus, Russia’s junior ally, is helping train Cuban troops—as Belarusian defense officials told The New York Post—then there’s a living supply chain of fighters stretching from Minsk to Moscow to Havana. It’s not a metaphor; it’s a pipeline.

The U.S. State Department called out Cuba by name. “The Cuban regime has failed to protect its citizens from being used as pawns in the Russia-Ukraine war,” it said in a statement to The New York Post. The phrase “pawns” lands hard. It implies not negligence but orchestration.

Even as Havana protests the U.S. embargo at the United Nations, it is exporting its own people into Russia’s war. Washington dismissed Cuba’s UN maneuvers as cynical optics—a bid “to victimize itself” while hiding “egregious crimes against the Cuban people.”

Kyiv is blunter. A senior Ukrainian official told The New York Post it is “highly plausible the Cuban government is complicit,” warning that the fighters will return with “modern combat experience against NATO-trained forces”—experience that could be used “against U.S. allies in Latin America.”

That’s the real issue: this is not only Russia’s war—it’s Latin America’s inheritance.

From Belarus to the Barrio: The Boomerang Risk

War is a teacher, and its lessons never stay put. When Cuban soldiers return home—or to neighboring regimes—they won’t just bring stories; they’ll bring skills.

A Ukrainian defense source told The New York Post that “combat experience is a dangerous and transferable commodity.” It can be sold to criminal networks, used to enforce repression, or loaned to allies. Thor Halvorssen of the Human Rights Foundation described Havana’s strategy plainly: “Cuba is a subcontractor of repression, serving Moscow’s wars abroad and silencing dissent at home.”

It’s not a new model—it’s just a new market. In the 1970s and ’80s, Cuban troops fought in Africa as revolutionary emissaries. In the 2020s, they fight for profit and survival. The Cold War idealism is gone; the infrastructure remains.

Cuba’s deep military and intelligence ties to Venezuela and Nicaragua make the prospect of returnees even more alarming. A few thousand veterans trained in Russian small-unit tactics, electronic warfare, and urban combat could serve as instructors for paramilitary forces or as shock troops against domestic opposition.

Think of it as a boomerang effect: men sent to fight NATO weapons in Ukraine could one day use those lessons against pro-democracy protesters in Caracas—or Havana itself.

EFE/ Sergei Ilnitsky

A Western Hemisphere Problem, Not Just a European War

It’s tempting for Washington to file the Cuban angle of the Ukraine war under “distant concern.” That would be a mistake. The Western Hemisphere is back in play.

The Trump administration has already shifted assets toward the Caribbean, using counternarcotics operations as a cover for naval presence. U.S. air and maritime patrols now overlap with Russian influence zones in the region. Add 4,200 combat-seasoned Cubans to that equation, and you have a hemispheric security dilemma, not a headline.

Policy needs to catch up with reality. Step one: stop treating Cuba’s UN theater as harmless. It’s part of a coordinated strategy to squeeze sympathy while deepening its Russian ties. Step two: treat the “volunteer” label for what it is—state-sanctioned outsourcing. Step three: plan for the boomerang.

That means tracking returnees, monitoring travel through Minsk and Moscow, and building intelligence cooperation with democratic allies in Latin America. It also means investing in police reform and civil-society resilience in nations most vulnerable to infiltration. If Havana and Moscow are rebuilding their networks, Washington and its partners must rebuild their guardrails.

The stakes extend beyond Cuba. “Cuba has become a strategic asset for an aggressor state,” the Ukrainian official told The New York Post, urging democracies to oppose Havana’s latest UN resolution.

The question is no longer whether the U.S. should act, but how—and how soon. Pressure in diplomatic forums, targeted sanctions on recruiters and facilitators, and sustained support for pro-democracy actors in Latin America are not provocations; they’re preventive maintenance.

Cuba insists these fighters left on their own. Perhaps some did. But patterns don’t lie. Once again, the island that once sent doctors abroad as soft power is sending soldiers to wage a hard war. The geography may have changed. The playbook has not.

Also Read: Bolivia’s Currency Crisis and the Battle Between Two Rights

In Ukraine’s trenches and in Havana’s ministries, an old game is being replayed—with new stakes for the hemisphere that thought it had outgrown it.