Haiti's Displacement Deepens to Over 1 Million as Gang Violence Escalates

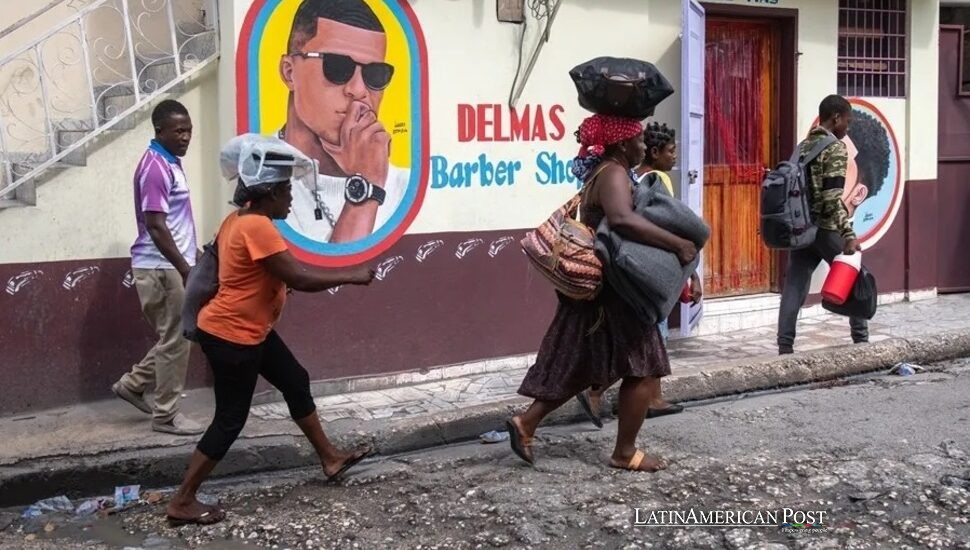

More than one million people in Haiti have been forced to flee their homes by relentless gang violence, marking a three-fold jump in the space of a single year, according to alarming new figures from the United Nations this week.

Surging Displacement Figures

The United Nations’ International Organization for Migration (IOM) shared that it now has over one million internally displaced people. This figure marks a notable tripling from December 2023’s count of about 315,000 individuals. The increase is most pronounced in and around Port-au-Prince, where an 87% rise in displacement was reported between 2023 and 2024.

The causes of this dramatic surge are tied directly to escalating gang violence—turf wars, kidnappings, and the widespread extortion of residents. According to IOM Spokesman Kennedy Okoth Omondi, many Haitians have been forced to flee multiple times as armed groups expand their control over neighborhoods. The organization says that these forced moves push families deeper into poverty and intensify the broader humanitarian crisis.

For a country long accustomed to socioeconomic and political strife, the current crisis stands apart for its speed and intensity. Gangs have grown so powerful that, in many areas, essential health services have collapsed. Disruption has caused food insecurity rates to soar among vulnerable groups, adding to the struggles of an already poor population. Children ‒ who form more than half of the displaced ‒ suffer most from this chaos, often missing formal education plus healthcare access.

Recent numbers highlight a grim truth for Haiti, which historically battles natural disasters, political turmoil, and economic instability. People face constant violence in their daily lives. Despite ongoing efforts by international agencies and NGOs to provide help ‒ the crisis keeps worsening ‒ casting a long shadow over the nation’s prospects.

Port-au-Prince Under Siege

Nowhere is the situation more apparent than in Port-au-Prince. According to multiple reports, gangs control up to 85% of the city’s territory. Individuals living in these zones are at the mercy of criminal groups that commit violence with near impunity. Families who manage to escape often do so with nothing but the clothes on their backs, fleeing at night to avoid detection.

Throughout the past year, displacement sites in the capital surged from 73 to 108, showing a shortage of good shelter options. Improvised camps in public buildings and schools ‒ plus deserted construction areas ‒ now seem normal for many who previously had stable homes. Food, clean water, and adequate sanitation remain scarce in these sites, threatening to unleash disease outbreaks.

The Haitian government recently swore in Mario Andrésol as the new state secretary of public security, hoping his experience—he served as director of Haiti’s National Police almost two decades ago—will help him rein in the violence. During his swearing-in ceremony, Andrésol vowed to fight gang activity, stressing the need to stop weapons plus drugs from entering the country. Haitian Prime Minister Alix Fils-Aimé appointed Andrésol and placed his hopes on “putting the right people in the right job” to restore some sense of normalcy.

Risks for everyday citizens stay high. The United Nations Human Rights Office noted that over 5,600 people were killed last year alone, a 20% increase from the previous year. Kidnappings, too, have soared, with nearly 1,500 reported during the same timeframe. As local and international authorities grapple with how to regain control of the capital, tens of thousands of ordinary Haitians face the likelihood of further displacement or worse.

A Broken System Under Strain

Beyond immediate physical danger, the collapse of crucial infrastructure and social services has compounded the crisis. Hospitals plus clinics in gang-heavy neighborhoods shut down or cut operations due to threats against medical staff along with theft of supplies. Many doctors and nurses leave the country or move to safer places, leaving whole neighborhoods without healthcare workers.

Healthcare collapses ‒ avoidable illnesses along with injuries remain untreated, leading death rates to rise. The economy struggles greatly. Companies shut down or cut operations, fearing kidnappings plus extortion. Schools ‒ often community hubs ‒ shut in dangerous zones, robbing children of learning and further unsettling communities.

Haiti’s agricultural sector suffers, too. Displaced people move from Port-au-Prince to rural zones, and this sudden influx strains limited resources. According to the IOM, people arriving in these rural zones frequently do so with little money or prospects, placing extra pressure on communities struggling with food production and access to clean water.

Further complicating the landscape is the forced return of an estimated 200,000 Haitians from abroad—primarily from the neighboring Dominican Republic—over the last year. Many are sent back without adequate resources, thrust into a country in turmoil where they have few connections or housing options. These returnees often end up in displacement sites, mingling with those fleeing gang-infested neighborhoods.

International assistance efforts are ongoing but face significant obstacles, including attacks on humanitarian convoys and looting of aid supplies. While the U.N.-backed multinational security force deployed in June aims to support the Haitian National Police, progress has been limited. The force is underfunded, and its personnel lack the equipment to confront heavily armed gangs operating with near autonomy.

Searching for Solutions

Given the magnitude of the crisis, long-term structural changes are needed to bring meaningful relief to Haiti. The Transitional Presidential Council (TPC), tasked with organizing long-overdue elections and restoring democratic governance, has been slow. The interim prime minister was replaced in November, but the new administration has made minimal progress in stabilizing the country or disarming the gangs.

Various global entities stress that significant international support is critical. Amy Pope, who runs the IOM, says ongoing help is needed to save people. Nearby aid groups ask for support, too ‒ time to stop a big disaster is running out.

U.S. immigration rules gave some relief to Haitian migrants with temporary status. Political shifts may happen. New laws like big deportations or cutting protections worsen the crisis by sending more at-risk people back to unstable places. The IOM warns that forced returns to Haiti could destabilize communities further and worsen security.

On the ground, local groups and community leaders start forming partnerships to protect neighborhoods plus negotiate truces with gang leaders. These efforts aim for stability in violence-filled areas ‒ though activists admit without stronger government oversight, actual law enforcement as well as international support, these actions only provide short-term relief.

Human rights advocates next to faith-based groups step in, offering shelter along with food plus counseling services for those who lost everything. Mental health support is key since many displaced Haitians struggle with trauma after seeing or facing violence firsthand. Children make up half of this displaced group ‒ they face school disruptions and psychological scars that may last a lifetime.

Haitian Prime Minister Alix Fils-Aimé insists on a national effort ‒ with international help ‒ to change things. He discusses a future where Haiti regains control over its land, giving “the Haitian people the peace they deserve.” Yet many Haitians feel skeptical after seeing repeated cycles of promises alongside failure.

Addressing Haiti’s displacement crisis demands multiple approaches: restoring public safety, strengthening institutions, providing humanitarian aid, and creating an environment ready for future elections. Mario Andrésol’s swearing-in signals a renewed focus on reining in gang power, but it will take more than personnel changes to break the stranglehold armed groups have on the nation. A working court system, proper government systems, and economic chances must be in the plan for long-term peace.

Haiti sits at a risky point. Over one million people now live displaced inside the country ‒ many moved several times ‒ and the nation’s fragile social structure collapses quickly. The government’s global groups, plus local organizations, must unite to stop violence and solve urgent aid needs, or else the displacement problem may grow worse ‒ leaving many Haitians without a safe future.

Also Read: Venezuelan Migrant’s Trial Casts Light on Tragic Murder Case

Among strong calls for more help, one idea stands out: Haiti’s citizens cannot wait forever. The longer the violence endures, the more challenging it becomes to rebuild systems that have fallen apart. For now, families continue fleeing their homes, seeking refuge from chaos—hoping that someday, they can return to a country no longer held hostage by gangs but guided by renewed hope and genuine peace.