Honduras’ Lagoon Guardians Hold the Line Between Hunger and Hope

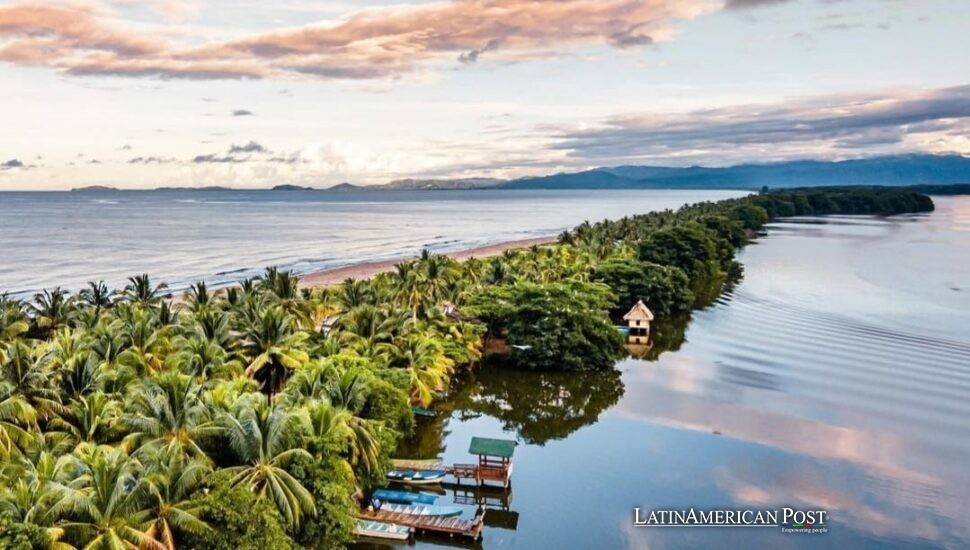

At Laguna de los Micos, a vast mangrove-fringed lagoon on Honduras’s Caribbean coast, the water is mirror-still at dawn. But below that surface lies tension—between sustenance and survival, protection and poverty. Here, fishers and rangers are testing an uneasy experiment: a yearly two-month fishing ban meant to save the lagoon that feeds them.

A nursery under siege

The lagoon is more than a body of water. It’s a cradle for life—a nursery where snappers, grunts, and countless reef fish spend their early months before heading into the open Caribbean. Local researchers estimate that about 80% of the region’s most valuable species begin here, hiding among mangrove roots and feeding in its calm shallows. “A beauty—a natural beauty,” one fisher told Mongabay, gazing over the water with a mix of affection and exhaustion.

To keep that beauty alive, 12 surrounding communities struck a fragile bargain. Every year, they stop fishing for two months to let stocks recover. During that pause, rangers from the PROLANSATE Foundation, sometimes joined by the military, patrol the channels, seize illegal gear, and remind their neighbors why the rules matter. Signs along the shoreline forbid harpoons, trammel nets, cast nets, and drag nets—methods that can strip a lagoon bare.

The principle is simple: leave the fish alone long enough for the lagoon to replenish itself. But as one ranger told Mongabay, enforcement isn’t about power. “We don’t take care of the fish for ourselves. We take care of them for the communities.”

Patrols, pushback, and the price of protection

On paper, the ban is unanimous. On the water, it’s a cat-and-mouse game. Rangers describe hidden nets coiled deep in mangrove thickets, fishers who bolt at the sound of an outboard motor, and occasional confrontations that edge toward violence. “They will not stop,” said one PROLANSATE ranger, his voice flat. “If they can crash into you, they’ll crash. And if they can sink you, that’s even better.”

The rangers serve as the lagoon’s first responders, documenting violations before the military steps in to confiscate gear or fine offenders. But the divide isn’t always between law and lawlessness. Many residents say enforcement feels uneven—that the poorest fishers, paddling dugouts with patched nets, face scrutiny while wealthier crews with faster engines and bigger spreads slip away. “Here we’re watching the law be enforced only upon people with low incomes,” one community member told Mongabay, echoing a frustration as old as the tides.

Rangers don’t deny the tension—or the danger. “Those of us who want to improve this resource are sometimes seen as enemies,” said another patrol member. Threats, he added, are common; some colleagues have quit after being harassed or cornered. Still, they stay on the job. Over the past season, PROLANSATE teams seized nine trammel nets, 14 cast nets, six masks, two rods, two harpoons, and four mosquito nets across all 12 communities. “Everyone is responsible,” a ranger said quietly. “That’s the reality.”

When rules meet hunger

The rule may be clear, but hunger blurs everything. Most families around the lagoon—leaders estimate about 95%—depend directly on fishing or crab gathering. The ban is meant to preserve their future, yet the present is unforgiving. “Every once in a while, people go out to fish because they could die of hunger,” one resident admitted.

Rangers say education is as vital as enforcement. They visit villages, explaining how the short pause keeps the lagoon alive. “This way, for the rest of the year, you have something to survive on,” said a PROLANSATE staff member. But when a patrol boat noses up to a dugout filled with nets, the conversation becomes personal. “Do you know we have a ban? Cast nets are strictly prohibited,” a ranger told one man during an encounter witnessed by Mongabay. The fisher nodded, promising to stop—for now. “If you come back and the military comes,” the ranger warned, “they’ll confiscate them again.”

The forbidden tools tempt everyone. Harpoons, banned nationwide, still appear in patrol reports; their users say they only hunt for food. But these weapons target the biggest breeding fish—the very ones that sustain future catches. It’s a moral tug-of-war between need and foresight, between the next meal and the next generation.

Recognizing this, PROLANSATE has begun training locals in basic finance and small-scale business, aiming to make the ban less punitive. But alternatives are scarce. As one ranger put it, “The hardest thing isn’t the patrols. It’s telling people not to fish when the kitchen’s empty.”

Proof of recovery—and a fragile peace

Despite the struggles, there are signs the lagoon is breathing easier. After the closures, scientists have recorded measurable rebounds in fish biomass and diversity. In the wider Tela Bay region, where commercial species have declined elsewhere, fish populations inside community-managed lagoons are stable—and in some cases, growing.

These are fragile victories, easily undone by complacency or conflict. Honduras remains one of the most dangerous countries for environmental defenders, where standing up for conservation can carry fatal risk. But Laguna de los Micos has become a rare experiment in coexistence: local rules enforced by local hands, with state support arriving only when needed.

The rangers know the odds. They also understand why they keep going. “Believe me, I fell in love with the park,” one said, leaning against his skiff after a long day pulling nets. “I want to keep protecting this area. All of us who work in conservation do this because we enjoy it—and because we love it.”

Also Read: Cuba Fights Pain and Mosquitoes While Chikungunya Spreads Like Gossip

As dusk bleeds into the mangroves, the water mirrors the fading sky. Somewhere, a heron steps through the shallows. The patrol boat drifts. Ahead lies a lagoon that feeds thousands—and tests a nation’s patience for compromise. Behind it, hand-painted signs remind everyone what the season demands. Between those edges, rangers and fishers try, again and again, to keep one small piece of Honduras alive for tomorrow.