Latin America Guerrillas Seek Unity as Trump’s Shadow Reaches Borders

After Nicolás Maduro’s arrest, Colombia’s insurgent map is shifting. A video from Iván Mordisco urges a ‘super guerrilla’ alliance against Donald Trump, as rumors of U.S.-backed operations rattle border towns and revive old fears of intervention across the greater homeland.

A Call From the Jungle With a Camera Rolling

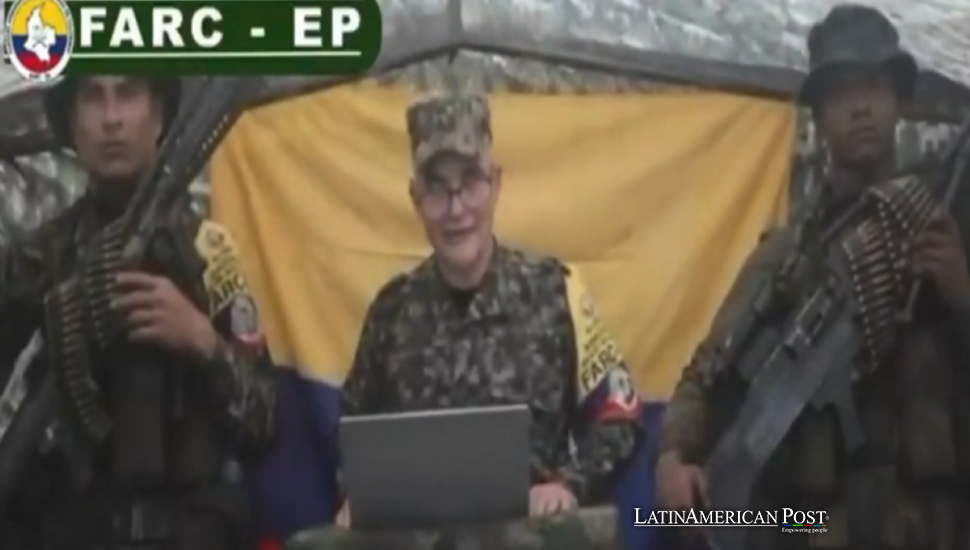

In the video described in reports, Néstor Gregorio Vera—better known as “Iván Mordisco,” and labeled Colombia’s most wanted insurgent leader—appears in camouflage, flanked by two heavily armed fighters. The staging is not subtle. It is meant to look like permanence, like a movement that survives presidents and headlines. But the message is less about bravado than urgency: after decades of bloody conflict over territory, drug routes, and illegal economies, he says the moment has arrived to stop fighting each other and face what he frames as a larger threat.

“The shadow of the interventionist eagle looms over everyone equally. We urge you to put aside these differences,” Vera says in the video, according to Reuters as cited in the report. He escalates from warning to almost-liturgical invocation. “Destiny is calling us to unite. We are not scattered forces, we are heirs to the same cause. Let us weave unity through action and forge the great insurgent bloc that will push back the enemies of the greater homeland.”

For people living along the border, this language is not abstract. It lands in the same places where armed groups collect “taxes,” where families learn to read the sound of motorcycles at night, where commerce is always accompanied by a second economy that no one admits, yet everyone understands. The report ties the intensified calls for unity to the aftermath of Maduro’s arrest, which has fueled fears among armed groups of a looming U.S.-backed military intervention. In Latin America, “intervention” is a word that doesn’t need footnotes; it carries its own weight, passed down like a warning from grandparents who still remember how quickly geopolitics can become personal.

The Border Where Wars Overlap and Civilians Pay

Among the groups singled out in Vera’s appeal is the left-wing National Liberation Army (ELN), described as Colombia’s largest and most powerful guerrilla organization, controlling vast stretches of the one thousand four hundred-mile border between Colombia and Venezuela. The geography matters. Borders in Latin America are not just lines on maps; they are corridors, escape routes, smuggling arteries, and—when states are weak—alternative sovereignties.

That is why the call for a cross-border “insurgent bloc” sounds like a nightmare to governments and a threat to civilians who are already trapped between uniforms. The report notes that the war between Mordisco’s FARC dissidents and the ELN has been “very, very bloody” with “a huge humanitarian impact,” in the words of security analyst Jorge Mantilla, speaking to The Telegraph. He points to the central contradiction: despite years of brutal infighting, Mordisco is still telling rivals to stop and unite against what he calls their shared enemy—“the US and its intervention.” Mantilla’s reaction is telling: “So the cards are on the table.”

In Tibú, Colombia, the report recalls a scene from Jan. 21, 2025, when police patrolled after guerrilla attacks killed dozens and forced thousands to flee in the Catatumbo region. The date and place matter because they show what “unity” among armed groups could mean in practice: more coordination, fewer rivalries to slow them down, and a sharper capacity to intimidate communities caught in the middle. For families living near these corridors, politics is not campaign rhetoric. It is whether a bus runs today, whether a store opens, whether a teenage son returns home without being recruited, accused, or disappeared into a cause he never chose.

Petro’s Gambit and the New Face in Caracas

The report says Colombian President Gustavo Petro, himself a former guerrilla fighter, seized on the threat of a united insurgent front to call for a concerted effort to “remove” drug-trafficking guerrillas. The phrasing is stark—“remove,” not negotiate—suggesting a pivot toward force or at least a tighter regional security posture. Petro also said he invited Venezuela’s new leader, Delcy Rodriguez, to cooperate in rooting out armed groups, a detail that underscores how fast the regional chessboard is changing in the wake of Maduro’s capture.

At the same time, the report notes that talk of a potential joint military operation involving the U.S., Colombia, and Venezuela has raised the prospect that the ELN could finally be dismantled after more than sixty years of insurgency. That possibility is exactly what makes Mordisco’s message feel like a flare shot into the sky: unite now, before the net tightens; stop bleeding each other, before someone else bleeds you.

The report adds that guerrillas operate along Venezuela’s two thousand two hundred nineteen-kilometer border with Colombia, and control illegal mining near the Orinoco oil belt. It describes the ELN as a Colombian Marxist guerrilla group with thousands of fighters and a U.S.-designated terrorist organization, operating in Venezuela as a paramilitary force. The group is believed to have around six thousand fighters, controlling key cocaine-producing regions, illegal mining operations, and smuggling routes, according to the report’s characterization.

After Maduro’s capture, the ELN vowed to fight to its “last drop of blood” against what it called the U.S. empire. Mantilla told The Telegraph that the group’s current aim is less about taking power in Colombia or rebuilding the Colombian state and more about defending the Bolivarian Revolution—because it sees itself as a “continental guerrilla” movement, “Latin Americanist” in inspiration, treating Venezuela’s struggle as its own.

Yet the report also suggests vulnerability beneath the rhetoric. Angelika Rettberg, a political science professor at the University of the Andes in Colombia, told The Telegraph she thinks the ELN is “in a very vulnerable position.” And she adds a cold reminder that cuts through the romance of unity: even if these factions managed to build a unified organization, that would not necessarily make them less likely to be hit by an eventual U.S. attack.

That is the haunting logic at the heart of the story. Armed groups call themselves heirs to a cause, but the people in the borderlands inherit something else: the fear that decisions made in capitals—Washington, Bogotá, Caracas—will be paid for in rural towns where the state arrives late, if at all. In this moment, the report suggests, the struggle is being recast as continental, the enemy renamed as intervention, and the old guerrilla dream repackaged as a “super alliance.” The question for Latin America is not whether such rhetoric will spread—it already has—but whether the region can stop history from repeating itself in the places where history always finds its easiest victims.

Credit: Fox News — By Emma Bussey

Also Read: Latin American Migrants Gain Protection as Neighbors Watch ICE Before Dawn