Mexico Case Unravels Cartel Empire from Tennessee Crash to Kingpins

What started as a car crash in a quiet Tennessee town exploded into a coast-to-coast dragnet stretching to Michoacán—exposing a meth empire, leaving a trail of bodies, and putting five alleged cartel leaders squarely in U.S. prosecutors’ sights.

From a Crash in Rockwood to the Mountain Labs of Michoacán

It began with a noise: the screech of tires, a fender crumpling into steel, and two men running from a wreck in Rockwood, Tennessee. Local police found the crash unremarkable—until they discovered what the suspects left behind. Hidden behind a nearby building was a hard-sided case packed with crystal meth.

It should have been a small-town footnote. Instead, it cracked open one of the most complex cartel investigations in recent memory.

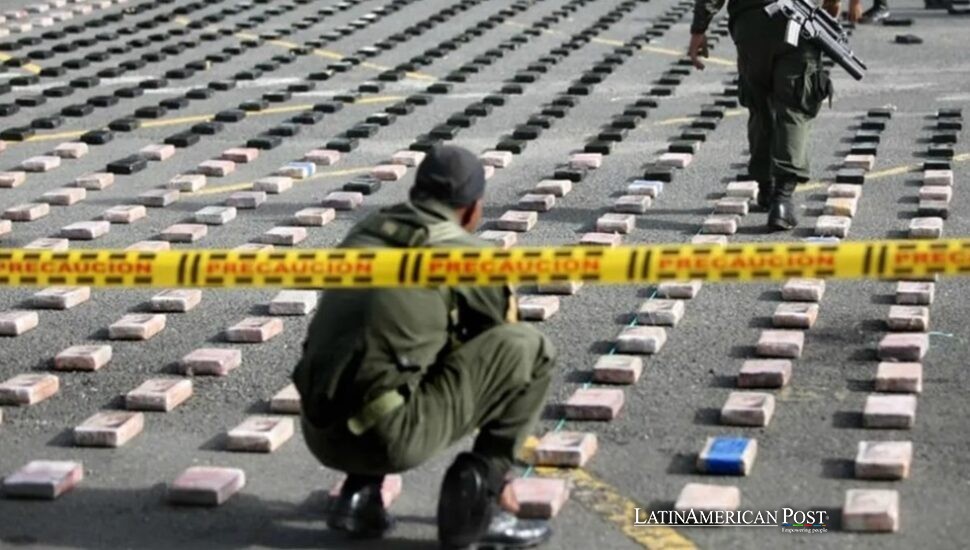

Phone numbers from the crash traced a latticework of logistics: cash drops, burner phones, safe houses. Agents from Tennessee to Atlanta began putting pieces together. Every time they found a stash house or a courier, the route pointed west—into Mexico’s mountainous state of Michoacán, stronghold of United Cartels. This criminal confederation runs meth labs and brokers deals with ruthless precision.

“This case is a vivid reminder that cartel violence and drug trafficking aren’t abstract problems—they land right here in our communities,” said Matthew Galeotti, acting assistant attorney general for the DOJ’s criminal division, in comments to the AP. “It started with a violent cartel and ended with shots fired at law enforcement on a U.S. highway.”

The border was not a barrier. It was a hallway.

Doritos, Wiretaps, and a Firefight on the Run

By early 2020, federal agents had identified a hub near Atlanta and a man they believed ran it: Eladio Mendoza, a trafficker allegedly moving meth from Michoacán into Georgia and Tennessee. One day, under surveillance, a man emerged from a hotel clutching an oversized Doritos bag. He crossed into Tennessee. State troopers tried to pull him over.

What happened next was chaos. The driver floored it, then pulled out an AK-style rifle and fired at police. One officer took a bullet in the leg. A second officer shot back, hitting the suspect. The Doritos bag, it turned out, held meth and heroin.

The man was no kingpin, but his phone was a Rosetta Stone.

Agents scoured the texts, calls, and money movements. They zeroed in on a semi-truck that had recently crossed from Mexico. When they stripped the trailer’s floor, they found nearly a ton of meth hidden inside. Later searches revealed even more narcotics—on a bus, inside homes. The road that began with a snack bag ended with enough meth to drown a city.

From Texts to Bosses: The Michoacán Connection

Digital trails pointed back to Michoacán—and to the top. Mendoza, court records say, was in regular contact with a man closely tied to Juan José Farías Álvarez, known as “El Abuelo,” one of the most powerful figures in the United Cartels. It was no longer just about couriers or intermediaries. The U.S. now had a line to the architects.

The timing was critical. Just weeks ago, the Trump administration officially labeled United Cartels as a foreign terrorist organization—a legal shift with real teeth. On Thursday, federal prosecutors indicted five men: Farías Álvarez (El Abuelo), Alfonso Fernández Magallón (Poncho), Nicolás Sierra Santana (El Gordo), and their alleged lieutenants Edgar Orozco Cabadas (El Kamoni) and Luis Enrique Barragán Chavaz (Wicho).

The Treasury Department followed with coordinated sanctions. The message: this is not just a criminal case—it’s a national security priority.

And yet, the lead suspect won’t face trial. After the meth-laden truck was seized, Mendoza fled back to Mexico. Prosecutors say he didn’t last long. In cartel math, losing a shipment is losing face—and often, your life. Mendoza was executed, according to sources familiar with the investigation.

Indictments, Rewards, and the Long Arm of the Court

The indictments are sweeping, but prosecutors know their targets remain out of reach—for now. All five men are believed to be in Mexico. But the U.S. is putting money where its mouth is: up to $10 million for El Abuelo, multi-million-dollar bounties for the others.

It’s not just talk. In February, Mexico extradited 29 cartel figures to U.S. custody—among them, Rafael Caro Quintero, the infamous Guadalajara Cartel founder charged with the 1985 murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena. On Tuesday, Mexico handed over 26 more, including a man charged with killing a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy.

Every transfer comes with conditions. Mexico refuses to extradite suspects facing the death penalty—a stance it has maintained for decades. But the cooperation is notable, especially amid tense political rhetoric on both sides of the border.

“We’re working closely with Mexican authorities,” Galeotti told the AP. “We believe they’ll help bring these individuals to justice.”

A Local Crash That Exposed a Global Pipeline

In Rockwood, Tennessee, the memory of a trooper bleeding from a gunshot wound is hard to forget. In Atlanta, a hallway surveillance tape shows a man walking with a Doritos bag full of heroin and meth. In Michoacán, avocado groves mask meth labs, and criminal alliances rise and fall with shipments.

What connected them was a crash.

A minor accident became the first link in a chain that pulled back the curtain on how drugs, dollars, and death flow from one country to another, often without warning. The men now under indictment allegedly operated in secrecy, under the radar—until a wreck made their world visible.

The case may yet set a precedent: that the U.S. can reach into Michoacán’s cartel command and hold its leaders accountable. But the deeper question remains: can the system do more than interrupt the pipeline? Can it dismantle it?

Also Read: Mexico Travel Warning Redraws Maps as Politics, Cartels and Tourism Collide

For now, a prosecutor’s desk holds indictments, a rewards hotline waits for tips, and five names sit at the top of a list built from a Doritos bag, a tractor-trailer, and a map that leads from a cul-de-sac to a cocaine corridor.

The fender-bender is over. The search is just beginning.