Mexico Mourns Slain Mayors as Cartels Target Democracy’s Weakest Link

After the daylight killing of Uruapan Mayor Carlos Manzo, Mexico faces a chilling reality: ten mayors murdered in one year, cartels turning local governments into battlefields, and underfunded towns forced to face organized crime alone.

A Día de Muertos Killing That Shattered a Nation

The gunfire began as music played. Candles flickered, families carried marigolds, and Uruapan’s plaza glowed with the orange light of Día de Muertos, the day Mexico remembers its dead. Then came the crack of bullets, and within seconds, Mayor Carlos Manzo Rodríguez was gone, his murder unfolding in public view before a crowd that had come to honor memory, not create new ghosts.

The killing stunned even a country accustomed to grim headlines. Uruapan, a city of 360,000 in Michoacán, is no stranger to violence. It sits at the intersection of rival cartels, each carving the region into fiefdoms of fear. The Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Los Viagras, and remnants of Los Caballeros Templarios all claim slices of the same territory, their battles waged over avocado profits and trafficking routes.

Authorities told EFE that Manzo had been under both federal and municipal protection since last year, reinforced only months before his death. The fact that armed men could pierce those layers and strike during a public event has turned the murder into a national symbol of impotence, a reminder that even surrounded by guards, Mexico’s local leaders remain exposed.

By official tallies reported to EFE, ten sitting mayors have been killed in the past twelve months, from Oaxaca to San Luis Potosí to Guerrero. Each death is more than a statistic; it’s a map of municipal fragility, where city halls double as frontlines and where the price of public service can be a funeral.

The Weakest Link in a Centralized System

Mexico’s constitution promises federalism, power shared among national, state, and municipal governments. But on the ground, that balance tilts hard toward the center. “The municipal tier is the weakest link in the country’s governing structure,” political scientist Javier Oliva of UNAM told EFE. “Mexico’s system looks federal, but it behaves like a centralist one.”

The contradiction leaves mayors carrying heavy responsibilities without the money or workforce to bear them. Local governments are expected to handle everything from sanitation to security, yet many operate on shoestring budgets, dependent on slow transfers from state or federal coffers. Municipal police, often the only visible arm of the state in small towns, are poorly trained and poorly paid, easy targets for intimidation or infiltration.

“That explains not just the security problem but urban services, health, everything,” Oliva said. “When the base of the pyramid cracks, the whole system shakes.”

The cracks are widening. Cartels don’t need to control Mexico City to control Mexico. They need mayors who can be pressured, police chiefs who can be bought, and city councils willing to look the other way. A phone call or a visit can suffice: sign this permit, ignore that convoy, grant this contract. Refusal is often answered not with negotiation but with gunfire.

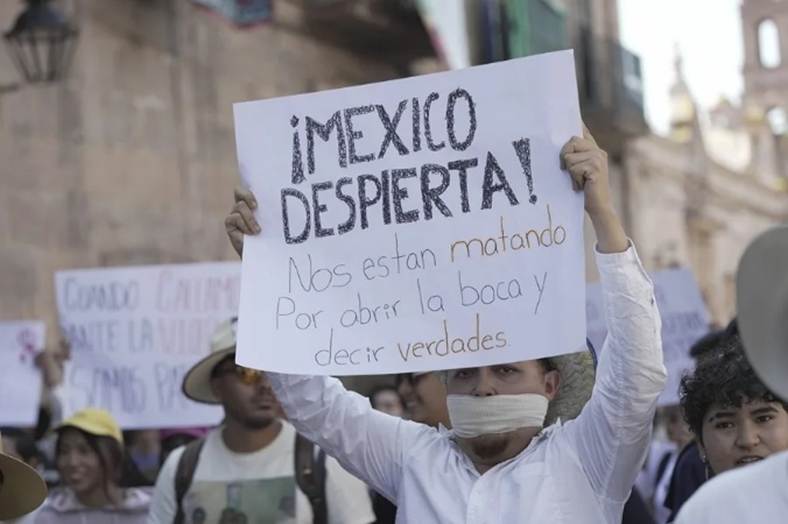

As a result, the very officials most rooted in their communities — the ones who should embody democracy’s reach — are being hunted.

Where Territorial Control Begins

The NGO Data Cívica has a name for this grim pattern: “Votar entre Balas” (Voting Between Bullets). In its analysis, cited by EFE, nearly 80% of victims of political-criminal violence in Mexico are local figures. The math explains itself: cartels rule through geography, and geography begins with the municipality.

City halls control contracts, police beats, and permits. Capture one, and you capture the levers of daily life: who builds the roads, who sells fuel, who collects trash. Through those levers flow the lifeblood of criminal economies: extortion, contraband, and protection rackets hidden in plain sight.

Michoacán is both a tragedy and a warning. The state has logged 25 attacks against political figures in 2025 alone, 88% of them municipal, according to figures shared with EFE. “It’s a declaration of impunity and defiance,” Oliva told EFE, noting that similar patterns haunt Oaxaca, Guerrero, Tamaulipas, Sonora, Sinaloa, and Guanajuato.

Each attack sends a message: the state cannot protect its own. Each funeral widens the space where the law should be. And every new mayor sworn in does so with the knowledge that holding office now carries a death sentence waiting to be enforced.

What Real Protection Would Look Like

This week, President Claudia Sheinbaum unveiled Plan Michoacán, a new initiative to combat violence in the state. It pledges to reinforce security forces and social programs, but, as Oliva noted to EFE, it stops short of addressing the core problem: the vulnerability of municipal governments themselves.

If Mexico wants to keep its mayors alive, protection cannot end with armored SUVs and two escorts. It must start with funding so that towns can hire competent police instead of desperate ones; with coordination, so intelligence flows between city, state, and federal forces; and with investigation, so the murders of local officials are treated not as isolated crimes but as a pattern of political terror.

“Protection means more than a bodyguard,” Oliva said. “It’s a structure that allows mayors to do their jobs without living in fear.”

That structure must include clear emergency protocols, reliable threat assessments, and legal channels for officials to report extortion without risking retaliation. It must also include transparency, public briefings that inform citizens when their leaders are in danger, and early warnings that allow events to be canceled without stigma.

For now, the gap between promise and practice remains fatal. In Uruapan, a mayor with two layers of security died in front of his constituents. The murder didn’t just end a life; it exposed a broken equation in which federal muscle can’t reach municipal ground fast enough.

Mexico’s democracy will not fall all at once. It will erode municipality by municipality, one silenced mayor, one captured police station, one plaza ruled by fear. The only counterforce strong enough to stop that erosion is the same one the country’s constitution imagined two centuries ago: law backed by equal protection.

In the plazas where mayors once stood, families now gather to light candles and tape photographs to broken walls. Marigolds return every Día de Muertos, but mourning cannot become routine. “Ten mayors in twelve months is not politics, it’s a failure of the state,” Oliva told EFE.

Uruapan’s square will fill again, its vendors reopening stalls and its children playing where gunfire once fell. What the town and the nation cannot afford is a return to silence. Mexico’s mayors are the front line of its democracy, and democracy cannot survive if its front lines keep falling.

Also Read: Cuba Puts Its “Fixer” On Trial: Alejandro Gil’s Fall From Reformer To Accused Spy