St. Lucia’s Ballot Reflects Crime Fears, Passport Debates, And U.S. Ties

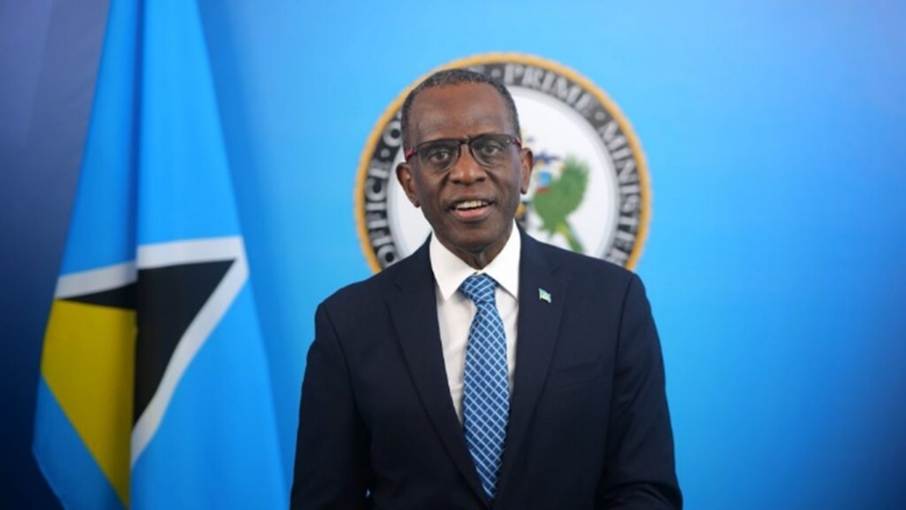

St. Lucia’s voters have handed Philip J. Pierre and his St. Lucia Labour Party (SLP) another term in power, reaffirming a social-democratic experiment built on cautious economic management, tourism dependence, and contentious passport sales. The verdict comes amid intensifying regional geopolitics and U.S. pressure around the island.

Election Results And A Clear Mandate

The election results highlight broader Caribbean shifts and regional geopolitics, making the outcome more relevant to regional geopolitics and economic development, helping readers understand its broader significance.

Official results showed the SLP on track to retain at least 13 of 17 seats in the House of Assembly, matching its current commanding majority with two constituencies still to be confirmed. Pierre captured 57.1% of the popular vote, comfortably ahead of conservative rival Allen Chastanet, whose United Workers Party (UWP) managed just 37.3%. For an island of roughly 180,000 people, that is a decisive verdict on Pierre’s first term and Chastanet’s promise of a sharp course change.

Chastanet, who preceded Pierre as prime minister, had hoped that the SLP’s landslide win in 2021 would be a one-term aberration. Instead, his UWP enters the new parliament with only a token presence – a single seat confirmed on election night, up from two but still a long way from power. It is the latest chapter in a remarkable pattern: the Caribbean island has now seen four consecutive elections in which the incumbent government was defeated, only for voters this time to turn around and re-endorse the administration they installed three years ago.

Crime, Cost Of Living, And Passport Sales

The campaign was shaped around three interlocking anxieties: the cost of living, surging violent crime, and St. Lucia’s reliance on citizenship-by-investment (CBI) – the sale of passports to wealthy foreigners – to fill its budget. Pierre pitched himself as the steward of stability, promising careful fiscal management and incremental reforms. Chastanet accused him of presiding over worsening security, partly because U.S. security assistance has been restricted under the Leahy Law, which bars American support for foreign units implicated in human rights abuses.

CBI, meanwhile, hovered over the race like a loaded question. The program is a vital source of revenue for St. Lucia and several neighbouring island states. Still, it has also become a flashpoint with Washington, which warns that “nefarious actors” from countries such as China or Iran can exploit loose vetting. The U.S. has responded with its own proposed “gold card” visa track for the wealthy – a reminder that big powers are not above monetising residency themselves. Chastanet demanded tougher audits and greater transparency for the island’s CBI scheme; Pierre insisted the program can be defended and improved, not scrapped.

Regional Upheaval And Global Pressures

St. Lucia’s vote comes in a week of political churn in the eastern Caribbean. In nearby St. Vincent and the Grenadines, the opposition swept almost all seats, ending Ralph Gonsalves’ remarkable 24-year run as prime minister. Across the sea, the U.S. is expanding a military buildup around Venezuela, ostensibly to clamp down on drug trafficking. The Dominican Republic and Trinidad and Tobago have already allowed U.S. vessels to dock; St. Lucia, whose economy is deeply tied to tourism, must carefully calibrate its stance. Security cooperation can help reduce gun and drug flows that fuel crime, but it also risks pulling the island into the orbit of bigger geopolitical contests it does not control.

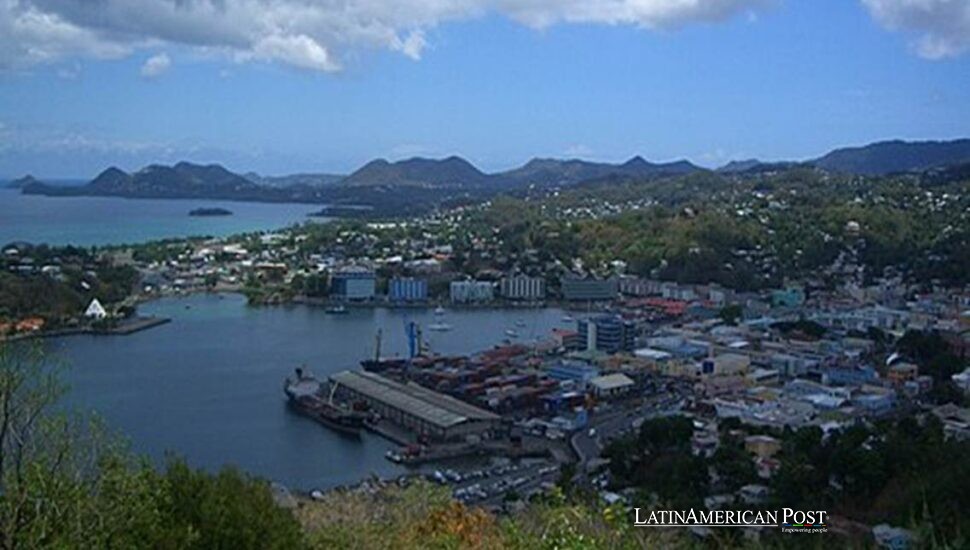

Against that backdrop, voters gave Pierre a mandate to keep steering between reefs. Tourism remains the country’s economic engine and largest employer. The island markets itself on postcard images of its twin volcanic spires, the Pitons, which rise from the sea over a UNESCO World Heritage Site of hot springs, coral reefs, and lush rainforest. Hotels, cruise ships, and resorts depend on a reputation for safety and stability – conditions that both the SLP and UWP claim to defend, even as they argue over whose policies better protect them.

Before mass tourism, St. Lucia’s fortunes were built on bananas, which replaced sugar cane after 1964. Today, bananas are still the second-largest source of foreign exchange after tourism, alongside crops such as mangoes and avocados. But global price pressures, climate shocks, and changing trade rules have undermined the old agricultural model. That leaves the country more exposed than ever to swings in visitor numbers and to external shocks such as pandemics or U.S. and European recessions. Pierre’s promise of “stability” is therefore both attractive and fragile.

St. Lucia’s history and identity reflect centuries of resilience and contested colonisation. Recognizing this continuity helps regional analysts and students appreciate how historical legacies shape current politics and policies, fostering a deeper understanding of the island’s commitment to stability and cultural preservation. St. Lucia’s social fabric reflects centuries of contested colonisation. Initially settled by Indigenous peoples who called it “Land of the Iguanas,” the island was contested by European powers before the British finally seized control in the early 19th century. Most St. Lucians today are descendants of enslaved Africans, brought by the British to work on sugar plantations. Although the island is a former British colony, French settlement in the 17th century left a profound cultural imprint. The local patois, St. Lucian Creole, keeps that legacy alive even as English remains the official language.

A Modern Political System Mirrors History

St. Lucia recognises Charles III as head of state, represented by a governor-general, but has been fully independent since 1979. Universal suffrage came in 1951; self-government for internal affairs followed in 1967. The country briefly joined the West Indies Federation, then charted its own path after the federation’s collapse. In 2003, parliament amended the constitution to replace the oath of allegiance to the British monarch with a pledge of loyalty to St. Lucians – a quiet but symbolic shift.

Pierre himself embodies the continuity and churn of St. Lucian politics. Sworn in as prime minister on July 29, 2021, he led the SLP to a sweeping victory that year, taking 13 seats and driving the UWP down to two. His re-election suggests voters still trust his approach, even amid stubborn crime rates and persistent economic inequality. For now, at least, they appear unconvinced that Chastanet’s tougher rhetoric on security or sharper criticism of CBI offers a better route forward.

St. Lucia’s media landscape is relatively plural, with mostly privately owned newspapers and broadcasters that carry a range of views. That diversity helped make this campaign a national conversation about the island’s future, not just a clash of personalities. Coverage spanned the familiar bread-and-butter issues of jobs and prices, as well as the more abstract questions of sovereignty, foreign influence, and how small states should finance their development without sacrificing control.

The island’s recent history is punctuated by reminders of both vulnerability and resilience: hurricanes, the banana-flattening Tropical Storm Lili in 2002, constitutional tweaks, shifting diplomatic recognition – such as the restoration of ties with Taiwan in 2007 and new cooperation agreements with Venezuela in 2023. Against that backdrop of constant adjustment, this week’s election result feels less like a revolution than an affirmation.

St. Lucians have chosen to stick with a government that promises gradualism amid turbulence. Whether Pierre can deliver safer streets, a cleaner CBI program, and a more resilient economy without alienating Washington or scaring off investors remains to be seen. But for now, under the shadow of the Pitons and the watchful eyes of larger powers, St. Lucia has opted for continuity – on its own terms.

Also Read: Venezuela Gangs And African Jihadists Drive Europe’s Cocaine