The Vanishing Line: Peru’s Mashco Piro and the Village Caught Between Worlds

In the farthest reaches of Peru’s Madre de Dios, where the Tauhamanu River cuts through forest so dense it seems to hum, a fishing hamlet lives with ghosts that breathe. They are not spirits, but people—the Mashco Piro, one of the last uncontacted Indigenous groups on Earth. Once only glimpsed in rumors and footprints, they now walk the riverbanks in daylight, drawn closer by the encroaching roar of chainsaws. Between fear and reverence, a handful of neighbors and park rangers try to preserve the most fragile pact in the jungle: coexistence without contact.

A Clearing, A Circle, And A Sprint to the River

On a humid morning in Nueva Oceania, a hamlet of seven families perched above the Tauhamanu, Tomás Añez Dos Santos heard the forest change tone. “I heard steps,” he recalled. “Then a whistle like a bird. And more—many more.” Seconds later, he saw them. “One was standing, aiming with an arrow,” he said. “He noticed me, and I started to run.”

The Mashco Piro had encircled his clearing, whistling, mimicking birds, their signals weaving through the trees. Tomás shouted the only word he knew: Nomole—brother. It was both a greeting and a plea. “They kept whistling. We felt them coming closer, so we ran to the river,” he said.

He harbors no anger. “Let them live as they live,” Tomás said quietly. “We can’t change their culture. That’s why we keep our distance.”

But distance is shrinking, and just beyond the village, logging concessions now hum at night. Villagers swear the Mashco Piro appear most often when the sound of machinery moves closer. Fear lives beside sympathy. They remember both the greetings and the arrows. Two years ago, two loggers fishing upriver were attacked; one died from nine arrow wounds. The survivor carried a shaft in his abdomen for miles before help arrived.

Every encounter is a test of restraint. “We leave them plantains,” Tomás said. “A way to say, ‘Take this, it’s yours. Don’t shoot.’”

No-Contact on Paper, Contradictions on the Ground

Peru’s law is clear: no contact. Modeled after Brazil’s policies, the doctrine forbids outsiders from approaching uncontacted peoples, whose immune systems cannot withstand even a mild cold. The rule was born of tragedy. When the Nahua people were contacted in the 1980s, half died within a few years. In the 1990s, the Murunahua suffered a similar collapse.

“Isolated peoples are very vulnerable,” said Issrail Aquisse of the Indigenous federation Fenamad. “Even the simplest diseases can wipe them out. And cultural interference can be just as deadly.”

Nueva Oceania, however, sits outside any formal reserve. That means villagers face encounters alone—no buffer, no backup. One morning, Letitia Rodríguez López, a young mother, heard “shouting, cries, as if there were a whole group” while she picked fruit. She dropped her basket and ran. “Because loggers are cutting the forest, they’re running too—maybe out of fear,” she said. “They end up near us. We don’t know how they’ll react. That’s what scares me.”

So villagers improvise diplomacy with plantains and silence. They know that shouting back or approaching too closely could trigger violence—or infection. It’s coexistence written in instinct rather than policy, sustained by the hope that both sides can remain invisible to each other long enough to survive.

At Nomole, A Ritual of Distance and Exchange

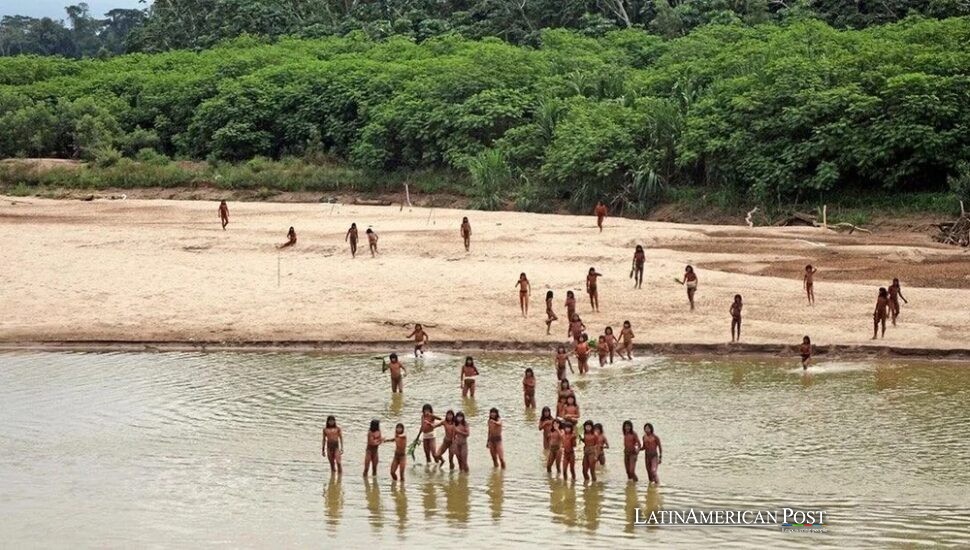

Nearly two hundred kilometers away, a control post called Nomole tries to give that fragile balance a structure. Eight rangers live there, working for the Ministry of Culture and Fenamad. They guard the border of a reserve where a separate Mashco Piro band appears regularly on a shingle beach across the river.

“They always come to the same place,” said head ranger Antonio Trigoso Ydalgo. “They shout from the bank, asking for plantains or sugarcane. If we don’t answer, they wait all day.” The rangers keep small gardens for such exchanges. When supplies run low, they ask the Mashco Piro to “come back in a few days.”

Over years of cautious encounters, the rangers have learned names and faces. There’s Kamotolo—Honey Bee—the stern leader; Tkotko, the joker, called Vulture; and Yomako, or Dragon, a young woman who laughs with the guards. Gifts move both ways: necklaces of animal teeth, a monkey-rattle for a ranger’s newborn. The Mashco Piro love bright colors—red, green, soccer jerseys torn and faded—so the agents wear worn shirts as offerings.

“They used to wear skirts made from insect fibers,” said ranger Eduardo Pancho Pisarlo. “Now, when tourist boats pass, they sometimes receive clothes or boots.”

What they never give, Antonio added, is knowledge. “Once, I asked how they light fires. They told me, ‘You already have all these things—why do you want to know?'” Even after a decade of gentle contact, the Mashco Piro remain mysterious—moving camps with the seasons, hunting and vanishing before dawn. Rangers estimate there are about forty individuals in this band, speaking a dialect linked to the Yine language—an echo of Peru’s deeper past still alive in the canopy.

EFE

A Future Written in Roads and Signatures

Nomole works because it is remote. After all, the forest still holds more silence than noise. But that silence may not last. A new government-backed road is planned to link the region to zones of illegal gold mining, a corridor likely to carry disease, guns, alcohol, and curiosity. It would cut straight through the Mashco Piro’s range.

A solution exists on paper: in 2016, Congress approved a reserve expansion to include the forests around Nueva Oceania. Nine years later, no president has signed it. “We need them to be free like us,” Tomás said. “They lived peacefully for years, and now their forests are being destroyed.”

Worldwide, there are at least 196 known uncontacted groups. Half could vanish within a decade if protections fail, experts warn. The threats are no longer just logging and mining but missionaries and influencers, chasing salvation or social media views.

Back in Nueva Oceania, Tomás walks to the edge of the clearing where he once froze, where the Mashco Piro’s whistles once circled him like a spell. He cups his hands and whistles again into the trees—a soft imitation, a question.

Also Read: Amazon Green Returns Even as Chainsaws Hum a Relentless Chorus

“If they answer,” he said, “we turn back.”

Only the insects reply. For now, the forest keeps its silence. And between the hum of chainsaws and the breath of the jungle, a handful of villagers stand guard over a vanishing line—the line that separates the known world from the one that still refuses to be known.