Venezuela Raid Rattles Caribbean Neighbors As Trinidad Bets On Trump

As the Trump administration forces Nicolás Maduro off the stage and into a US jail, the Caribbean feels the tremor. From Trinidad and Tobago to Caricom, leaders weigh law, oil, crime fears—and Washington’s long shadow as families brace for fallout.

A Radar Appears, And The Sea Suddenly Feels Crowded

The year 2026 opened with the kind of headline that makes small countries feel even smaller: Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, ousted and imprisoned on US soil by the Trump administration. In capitals across the region, the legal arguments come first—violations of sovereignty, the blunt force of power, the uneasy silence from the world’s usual referees. But on the islands, the story lands differently. It becomes a kitchen-table question, spoken low: if this can happen to Venezuela, what does it mean for the rest of us?

This feature draws on the original reporting, interviews and quotes published by The Guardian and journalist Nesline Malik, whose account traces how the shockwave travels through a region that lives close to the water and even closer to consequence.

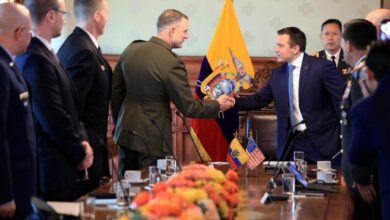

One detail from that reporting feels like a symbol dropped into the surf. On 28 November, a US Marines radar system appeared in a coastal neighborhood of Tobago, a deployment the New York Times described as “a state-of-the-art mobile long-range sensor known as G/ATOR”—equipment worth tens of millions of dollars. Alongside it came US military jets and troops, arriving on an island only 7 miles from Venezuela. For residents, the distance is not an abstraction. It is a boat ride, a horizon line, a relationship built over decades of commerce, migration, family ties and fuel.

What makes the radar more than hardware is the politics wrapped around it. Kamla Persad-Bissessar, prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, has openly aligned herself with Donald Trump in a way that separates her country from the broader instincts of the Caribbean Community (Caricom), a bloc of 15 nations that has long tried—imperfectly, but intentionally—to speak with one voice when big powers lean in.

Dr Jacqueline Laguardia Martinez, a senior lecturer at the Institute of International Relations at The University of the West Indies, told Malik that Trinidad and Tobago has “openly endorsed US actions under the pretext of combating transnational crime.” Those words matter because “combating crime” is an argument that travels well in a region battling real violence, even when the methods are murky and the collateral damage is measured in bodies.

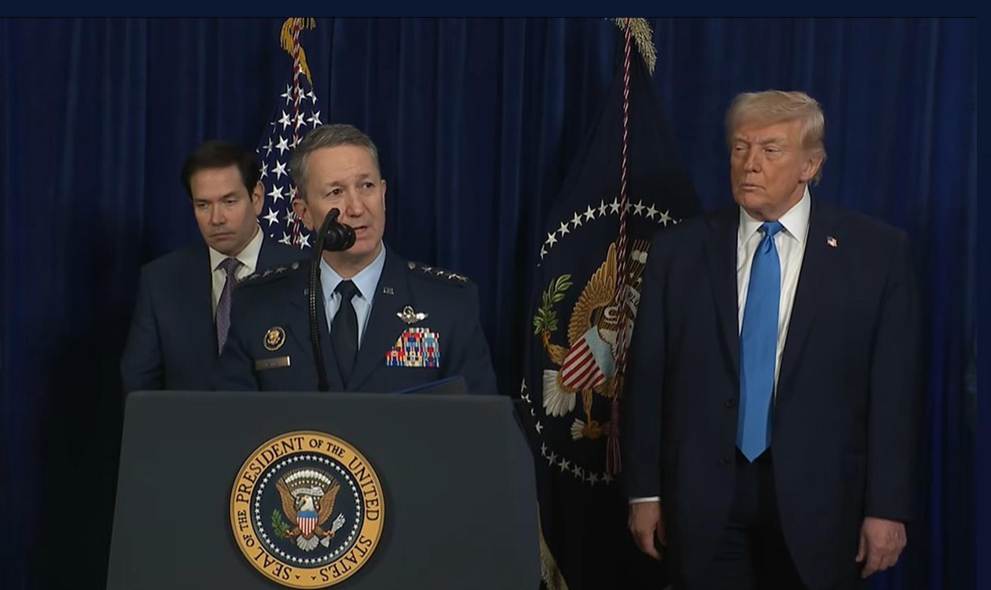

Since September, the US has carried out at least 21 airstrikes on alleged drug smugglers across the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, killing more than 80 people—reportedly including several Trinidadian citizens. For families who already live with the grief of gang wars and an overwhelmed security apparatus, these numbers do not read like policy. They read like warning.

At home, Persad-Bissessar has framed her posture in moral terms, saying she has “no sympathy for traffickers.” Her country—population about 1.5 million—has been struggling with rising homicides and gang violence, recording 624 homicides in the previous year. In that context, it is easy for a government to present deeper military cooperation as a hard but necessary bargain.

Yet the timing makes the bargain look less like a local crime strategy and more like regional staging. In mid-November, Venezuela accused Persad-Bissessar of helping the US seize an oil tanker. In December, Trinidad and Tobago allowed US military aircraft to transit through its airports, insisting the flights were for “logistics” purposes. In the shadow of Maduro’s capture, those earlier decisions start to resemble a runway being laid, one permission at a time.

Gas Hunger Meets A Superpower’s Appetite

Inside Caricom, the fracture is not just about diplomacy. It is about resources. Peter Wickham, director of Caribbean Development Research Services, told Malik that while Trinidad and Tobago could argue its facilities were not used to “stage an attack,” he still sees “cooperation at least in the provision of intelligence.” More telling, he said, is that other countries refused similar steps. Grenada and Antigua were asked to install the radar, he said, and they said no.

Why would Trinidad and Tobago say yes? Wickham offered a blunt explanation that turns geopolitics into a story of needs colliding. “She and Trump have something in common,” he said, “in that they both want resources from Venezuela. Trump wants oil, she wants gas.” He argued that Persad-Bissessar has decided the best path is not negotiating with the Maduro government but negotiating with Trump, hoping Trump will deliver Venezuela’s gas.

This is not a minor temptation. Trinidad and Tobago’s previous approach involved long discussions with Venezuela, with US permission, about developing Venezuela’s Dragon Field near Tobago waters—estimated at roughly 4.2tn cubic feet of gas. In the Caribbean, energy is never just about profit; it is about keeping lights on, stabilizing economies, paying for schools and hospitals, and reducing the vulnerability that comes with import dependence. But a strategy that depends on a volatile patron can also turn a country into a proxy, or worse, a pretext.

The risks deepen when legal consequences enter the frame. Laguardia Martinez described Trinidad’s posture as a “divergent adversarial stance,” warning that Caricom has historically defended Latin America and the Caribbean as a “Zone of Peace” anchored in the multilateral order that emerged after the second world war. In Wickham’s view, Trinidad and Tobago is “taking positions” that could end up before the ICC, given what he called “clear extra-judicial actions.” The irony is sharp: the US is not part of the ICC, but Trinidad and Tobago is.

In Latin America, where the memory of intervention is not academic but inherited—passed down like family lore—this is the familiar pattern. The strongest country speaks in the language of security, and smaller nations are left to decide whether cooperation buys protection or simply paints a target.

Caricom’s Hush, And The Fear Beneath It

If Trinidad looks like an outlier, the rest of the region looks cautious to the point of paralysis. Wickham told Malik that Caricom is “taking the path of least resistance” by avoiding a joint statement condemning the US operation. “It’s unfortunate,” he said, “but I am entirely unsurprised.” The hesitation is not only about dependence on aid or trade. It is also about what comes next.

Many Caribbean governments have genuine, historically grounded links with Venezuela, ties that can be reframed as guilt if the prosecutor is powerful enough. Venezuela’s petro-diplomacy ran through Petrocaribe, launched in 2005 by former president Hugo Chávez, offering favorable financing and credit terms for oil. It expanded through Alba, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, with broader ambitions for south-south cooperation. The West Indies oil company in Antigua is partly owned by Venezuela.

Beyond fuel, there is also the record of aid. After Hurricane Maria devastated Dominica and Barbuda, Wickham said it was Venezuela under Maduro that restored communications after networks were destroyed. “It was essentially the Venezuelan coastguard that was the first port of call,” he said. He warned that these legitimate relationships could be rebranded as “narco-related” if Trump chooses to weaponize them. “There are several Caribbean leaders that were close to Maduro,” he said, noting that Venezuela helped build the airport in Saint Vincent.

The intimidation is not hypothetical. Wickham pointed to language in the US indictment of Maduro that references other leaders who have “facilitated and supported him,” reading it as a signal: “we’ll be coming for you next.” That fear is compounded by watching bigger powers hesitate. If Keir Starmer in London and President Macron in Paris will not plainly condemn the operation, Wickham asked, how can leaders like Mia Mottley in Bridgetown or governments in Kingston feel safe doing so?

For the Caribbean, the question is not whether the region disapproves in private. It is whether silence becomes a habit that rewrites the rules of belonging. “This changes everything,” Wickham said. With elections coming up in three islands this year, he imagines leaders asking themselves a chilling question: “Do I want to call an election when I can be on a US hitlist?” In a hemisphere shaped by proximity to Washington, that is how sovereignty erodes—not in one dramatic coup, but in the slow, anxious recalculation of what a small nation dares to say aloud.

Also Read: Latin American Armies Face Trump’s Shadow Seeking Unseen Shields Now