Between Safety and Silence, El Salvador Weighs the True Cost of Bukele’s Crackdown

More than two years into El Salvador’s sweeping anti-gang crackdown, murder rates are down, but fear, censorship, and reports of torture are rising. As emergency powers stretch on, the question isn’t whether they work. It’s what they’re turning the country into.

When the Exception Becomes the Rule

What began as a temporary response to a crisis is starting to feel permanent.

In March 2022, after a weekend of gang killings that left more than 80 people dead, President Nayib Bukele declared a nationwide state of exception. The move gave security forces the power to detain anyone suspected of gang ties—no warrant, no due process required. The country’s legislature, controlled by Bukele’s party, approved the measure within hours.

At first, the results looked extraordinary. Homicides plummeted from 38 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 to single digits by 2023—numbers that made international headlines. Government ministers declared whole neighborhoods “liberated” from gang control. Many Salvadorans, especially in working-class districts long terrorized by MS-13 and Barrio 18, felt a relief they hadn’t known in decades.

But behind the stats, another picture is forming. More than 87,000 people have been jailed since the crackdown began. According to rights groups, at least 415 of them have died in custody. Over 6,000 complaints of abuse—mostly arbitrary arrests—have been filed.

“People are safer from gangs, yes,” says Samuel Ramírez, a legal advocate with the Movement of Victims of the Regime. “But now they fear the state.”

In many cases, fear is precisely the point. Political scientists at José Simeón Cañas University warn that sustained popularity—Bukele still polls above 80%—can mask an environment where dissent is dangerous, not absent.

Fear Behind the Applause

In interviews with EFE, several Salvadorans said the same thing: they appreciate the calm in their neighborhoods, but they watch what they say. And who might be listening?

A 54-year-old fruit vendor in San Salvador, identified only as Carmen, says she no longer attends neighborhood meetings about water shortages. “You never know who’s taking pictures,” she says.

She’s not being paranoid. The Washington Office on Latin America reports that the crackdown is now being used to silence not only suspected gang members but also journalists, labor activists, and community leaders. Amnesty International has documented an “alarming rise” in intimidation of anyone questioning the regime.

José Miguel Cruz, a sociologist at Florida International University, says it follows a pattern seen in other countries: security emergencies create public consensus, then slowly expand to target critics. “We’ve seen it in Egypt, in the Philippines. Now we’re seeing it in El Salvador.”

Several journalists have fled the country. Others now work with encrypted messaging apps and digital hygiene guides. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has granted protective measures to media outlets after traces of Pegasus spyware—the same software used by authoritarian regimes—were found on their phones.

Inside the Prisons, No One is Watching

The darkest corners of the crackdown are behind bars.

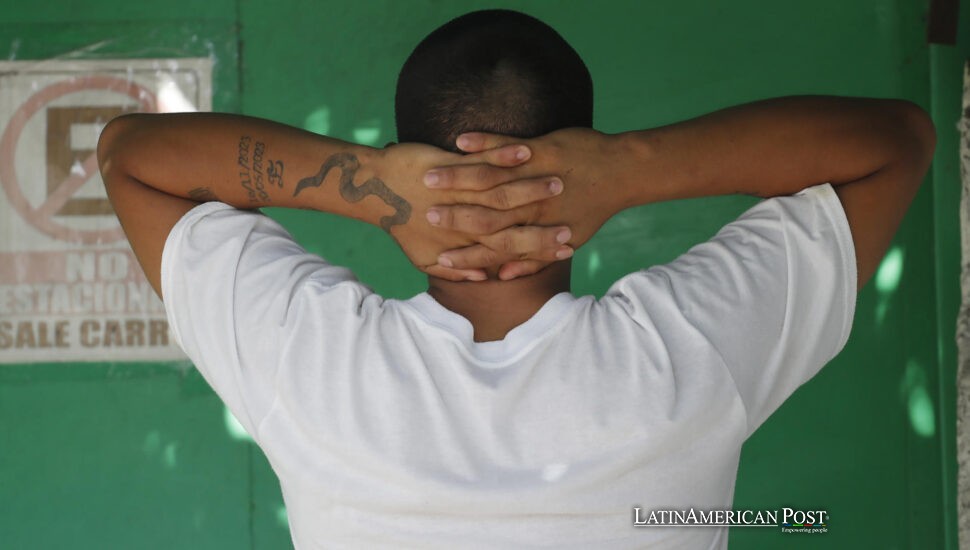

El Salvador’s sprawling new Terrorism Confinement Center—or Cecot—was unveiled in early 2023 with sleek drone footage of thousands of shirtless prisoners, heads shaved, crouching in rows. The video went viral. But no one outside the government has been allowed inside.

“We are convinced that cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment is widespread,” says Ingrid Escobar, a human rights lawyer at Socorro Jurídico Humanitario.

Her team has collected testimonies from smaller prisons still accessible to families, if they pay bribes for updates. Former detainees describe beatings, food deprivation, sleep deprivation, and suffocation used to extract confessions. One man, Kilmar Ábrego, deported from the U.S. and later released, detailed these abuses in legal filings first reported by EFE.

The World Organisation Against Torture now ranks El Salvador alongside Russia and Libya for custodial abuse risk.

Criminologist Jonathan Rosen of Holy Family University says the old prison system—violent—once allowed gangs to self-govern behind bars. Today, that autonomy is gone, replaced by near-total control. But what’s growing instead? Disease? Extremism? No one knows. “Hyper-control is not the same as reform,” Rosen warns.

A Future Held Hostage to the Present

Researchers who study democratic backsliding point to a sobering pattern: once emergency powers take root, they rarely go away.

At Stanford’s Varieties of Democracy Institute, studies show that in seven out of ten countries, states of exception become permanent tools of control when courts are weak and legislatures are loyal. El Salvador checks both boxes.

Since March 2022, Bukele’s Legislative Assembly has renewed the emergency measure every month, without debate, without oversight. Each time, the argument is the same: the threat isn’t gone.

But as human rights lawyer Paola Álvarez told EFE, “At some point, when the exception becomes routine, it is no longer legal. It is just power.”

The long-term consequences may arrive not with protests, but with money. The U.S. State Department has already placed several Salvadoran security officials on its corruption watchlist. The European Parliament condemned the wave of mass arrests. And after Bukele’s bitcoin gamble rattled the country’s credit ratings, El Salvador badly needs multilateral loans—loans that could soon come with human rights strings attached.

Inside the country, daily life is full of contradictions. Candlelight vigils for detained sons happen on the same blocks where shopkeepers celebrate record sales. University students debate whether to emigrate before activism becomes treason.

“The gangs are gone,” Ramírez says. “But so is trust.”

Bukele’s crackdown has undeniably changed El Salvador. Streets once patrolled by gang lookouts now feel walkable. But in place of extortion and fear, many neighborhoods now carry a different silence—one enforced by surveillance, arrests, and whispered warnings not to speak out.

Whether that silence lasts—and what replaces it if it breaks—will shape the country for years to come. The price of peace, it turns out, may be freedom. The question El Salvador now faces is whether it can reclaim both without falling back into bloodshed.

Also Read: Untold Silence: How Latin America’s Bloodshed Became Background Noise

Credits: Quotes and reporting from EFE interviews with Samuel Ramírez, Carmen, Ingrid Escobar, and Paola Álvarez; data from the Washington Office on Latin America, Amnesty International, Stanford’s Varieties of Democracy Institute, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and the World Organisation Against Torture.