Colombia Moves to Shater Escobar Criminal Myth with Merchandise Sale Ban

A recent law proposal in Colombia seeks to stop merchants from selling items that feature Pablo Escobar’s name or likeness. The people in favor of this step believe it stands to end the appeal of a drug kingpin who killed and harmed countless citizens. The change aims to change people’s thinking about Colombia’s history.

Standing Against Glorification

For decades, the specter of Pablo Escobar has hovered like a dark cloud over Colombia’s cultural landscape. At the height of his power, Escobar’s Medellín cartel stood behind bombings, hijackings, and murders of thousands—ordinary citizens, journalists, politicians, judges, and even children. Despite, or perhaps because of, the shocking violence, Escobar’s name and image became ubiquitous in mainstream media. Books, TV shows, and comedic references have woven him into pop culture.

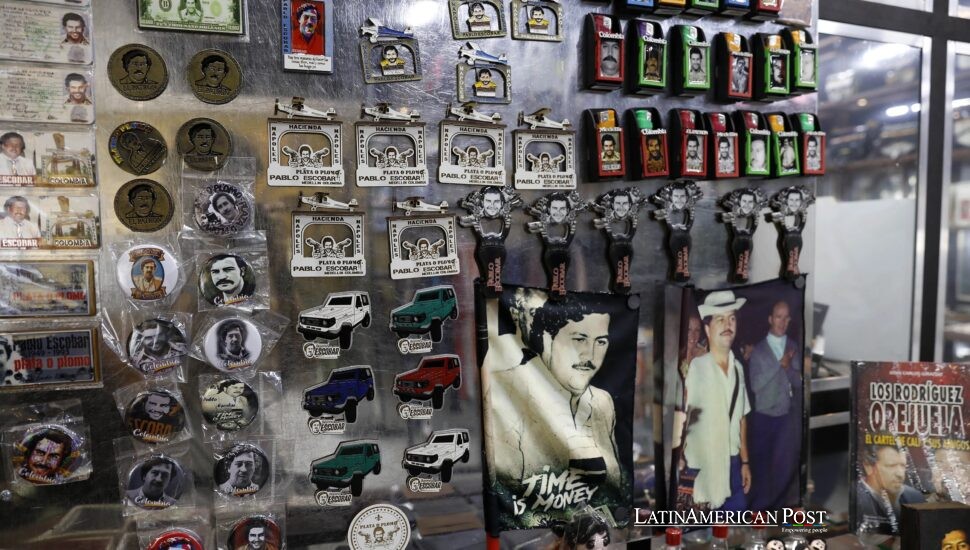

Some blame Hollywood’s fascination with “bad boys” for distorting how the public, especially younger generations, perceive a figure like Escobar. A Netflix drama might reduce him to a charismatic antihero, leaving viewers with only a faint sense of his unleashed devastation. At stores across Colombia, consumer items from shirts to coffee cups exploit Escobar’s image, making death into a business venture. Sellers claim these items serve tourists seeking knowledge or academics doing research. However, making trinkets from acts of cruelty ignores the actual pain of those affected.

A law under review in Colombia seeks to stop the sale of items celebrating Escobar and similar criminals. The proposed rules protect fundamental freedoms yet set reasonable limits. They uphold dignity for victims of narcotics violence and maintain truthful accounts of what occurred.

Eliminating Escobar-themed products is about more than just removing T-shirts from a few vendors. It targets the misappropriation of trauma for quick cash. It confronts the insensitivity behind celebrating a man who bombed an entire passenger plane and orchestrated endless atrocities. The law’s supporters argue that every purchase of an Escobar souvenir tacitly endorses a twisted legend—one that overshadowed countless stories of heartbreak and tragedy.

Recognizing the Victims’ Real Pain

The testimonies from people harmed by Escobar’s brutality stand as a central part of this discussion. From 1980 to 1990, deaths kept rising in Medellín, with his drug operation taking the blame for most attacks. During 1989, countless citizens remember how explosions tore apart main squares plus distant landing strips, turning that period into a time of unrelenting dread. By the time the dust settled, many families had lost fathers, mothers, children, neighbors, or mentors.

No single act underscores the cruelty of this era more than the Avianca Flight 203 bombing in 1989. In the space of moments, the Medellín cartel’s orchestrated explosion wiped out 107 passengers and crew, along with bystanders on the ground. Children would later learn of their parents’ demise through hushed conversations and frantic phone calls. The pain of losing a loved one in such a senseless attack continues to ripple through survivors’ stories. Undoubtedly, the trauma is still raw for them.

For instance, individuals like Gonzalo Rojas—who lost his father in that bombing—still live with the emotional scars. He shares how, at age ten, he was taken out of his classroom to learn that his father had been killed. Does it not cheapen that loss to see mugs or T-shirts fetishizing the very man who orchestrated this ruthless tragedy? Many of us cannot fathom the depth of heartbreak if confronted by an “Escobar for President” T-shirt, as some items feature, callously displayed in a market stall. The commercial celebration of a man who inflicted such overwhelming sorrow cannot be brushed aside as innocent free enterprise.

Critics might claim a law banning Escobar-themed merchandise edges uncomfortably close to censorship. Yet consider the examples cited by supporters: In Germany, you don’t see Adolf Hitler T-shirts or swastikas in mainstream souvenir shops. If these items appear, they are typically restricted, heavily regulated, frowned upon, and, in many cases, strictly prohibited. The same logic applies to other countries that have endured horrific regimes. For some tragedies, the moral impetus is that certain forms of profit-based exploitation cross a line.

Yes, Escobar’s violence differs from that of a genocidal dictator. Still, the principle remains consistent: commercializing the image of a notorious criminal is a slap in the face to those who endured immeasurable pain. Meanwhile, the synergy between big business, cheap tourism, and a global thirst for “narco-chic” sensationalizes an ongoing healing process for Colombians.

Fostering a Healthier Historical Memory

None of these arguments suggest that Colombia or the world should bury the memory of Escobar or pretend his chapter of violence never occurred. On the contrary, historians, educators, and local communities must examine that horrifying era thoroughly. Several proponents – among them family members who lost loved ones to Escobar’s actions – ask for state money to create displays at institutions that tell the true story of Colombia’s narcotics battles. The next wave of citizens will grasp the destruction these criminal groups brought to their communities through extensive studies, recorded accounts on film, and thoughtful writings about those times.

In contrast, a T-shirt plastered with Escobar’s mug or a coffee cup that declares “Pablo, President” transforms that historical reflection into an offhand novelty. On the contrary, a T-shirt that shows Escobar’s face or a coffee cup that reads “Pablo, President” turns history into a casual novelty. The ban stops the gap between a careful look at the past and quick sightseeing. Society must choose between facing a painful past honestly and turning it into cheap profit. These differences seem clear, and the ban reflects deep ethical conviction.

Some might argue that these items feed local vendors, who claim around 15–60% of their stall revenue might come from Escobar souvenirs. The fear is that a ban would deprive them of needed income. We must not let the short-term profits overshadow the broader ethical line. Suppose a chunk of your business relies on selling a murderer’s face. That points less to robust entrepreneurship and more to the unfortunate phenomenon that many visitors treat Medellín’s or Colombia’s tragedy like an edgy brand.

In any case, vendors still have myriad options. Colombia’s rich and vast cultural tapestry: from Andean crafts to indigenous art, from coffee products to modern local designs. If tourists desire local authenticity, they can do so without romanticizing narco-violence. The same logic stands for local entrepreneurs. They can quickly pivot to creations that reflect the genuine beauty of Colombian culture—stunning visuals of Comuna 13’s transformation or vibrant tributes to Afro-Colombian traditions. An entire universe of themes remains outside Escobar’s singular, grisly story.

Education Over Sensationalism

Ultimately, the proposed law calls for deeper reflection on how society processes traumatic history. We often unconsciously glamorize criminals when we turn them into pop-culture icons. This is especially true when film studios or TV networks spin narratives about “charismatic kingpins.” The result is a global audience that might admire the cunning or bravado of these criminals while losing sight of the thousands of innocents left in the crossfire.

A key criticism from some victims’ groups, including survivors like Rojas, is that the new bill focuses more on banning products than on encouraging robust education. It might, in principle, eliminate the T-shirts, yet fail to explain why we must never revere men who orchestrated mass murder. However, the law can prompt a broader public conversation and pave the way for more formal educational initiatives. People should not simply see it as “illegal to sell Escobar T-shirts.” They should understand that stance’s historical, moral, and empathetic rationale.

A suggestion ties the ban to museum displays, school lessons, and guided walks that show the harm cartels caused. Soon, newcomers will pick trips that honor victims or reveal how the town rebuilt its streets, not stir up gangster life. In Comuna 13 and other once-violent districts, local guides can share personal testimonies of transformation, artistry, and hope, reframing the narrative from the vantage point of those who overcame fear.

Those who question restricting the sale of certain items as paternalistic or controlling are offered a different perspective. This isn’t about muzzling free expression. People remain free to analyze Escobar’s story, produce documentaries, or critique the government’s response to the drug trade. They can debate the complexities of modern-day trafficking. But the line arises when commerce glorifies or trivializes vast human suffering. Some lines in society are worth drawing.

Even in other contexts, from Germany’s stance on neo-Nazi memorabilia to Italy’s minimal tolerance for Mussolini iconography, we see how moral imperatives shape the boundaries of commerce. The ban is consistent with a broader principle: a stance that profits should not be gleaned from glamorizing traumatic chapters. For too long, a “narco-chic” industry has overshadowed the pleas of living victims in Colombia. If we truly respect them, we must shift from fetishizing Escobar’s lurid legends to acknowledging the heartbreak he inflicted—and continuing the renewal that many in Medellín or across Colombia champion.

What we see in this proposed legislation is a distinct assertion of values. Wary of sensationalist narratives, Colombians declare that Escobar’s name should not be a marketable commodity. As a society, we should not trade in the memory of those harrowing bombs, kidnappings, and assassinations for easy tourist dollars. Understandably, many share an appetite for “dark tourism,” but the line must be drawn when it brushes aside the pain inflicted upon thousands of families.

By championing this ban, Colombia underscores its desire to step out from the shadow of the darkest era in its recent history. Far from rewriting or erasing that chapter, this measure urges us all to remember it more responsibly—perhaps even more poignantly—without trivializing the anguish that shaped entire generations. Escobar’s crimes are not a T-shirt slogan; they are the lived nightmares of real people.

Also Read: Mexico’s Judicial Reforms are Indefensible

The conversation is complex, and bills alone do not solve cultural memory challenges. But every journey toward healing and transformation begins with symbolic steps, and that includes regulating how we publicly represent a mass murderer. Colombia has a wealth of heritage, from its Andean highlands to Afro-Caribbean rhythms, from magical realist literature to contemporary innovation. Let these be the symbols on our mugs and T-shirts, not the face of a narco-terrorist. By passing this law, the country moves closer to a future that honors life over violence, memory over myth, and dignity over quick profit.