Colombia’s Child Sicarios Echo Escobar Era in Digital Age Recruiting

A single teenager squeezing a trigger at a Bogotá rally has torn Colombia’s fragile calm away. The alleged hitman is fifteen. His target, Senator Miguel Uribe Turbay, still fights for life. Behind both lies a market where childhood is merchandise.

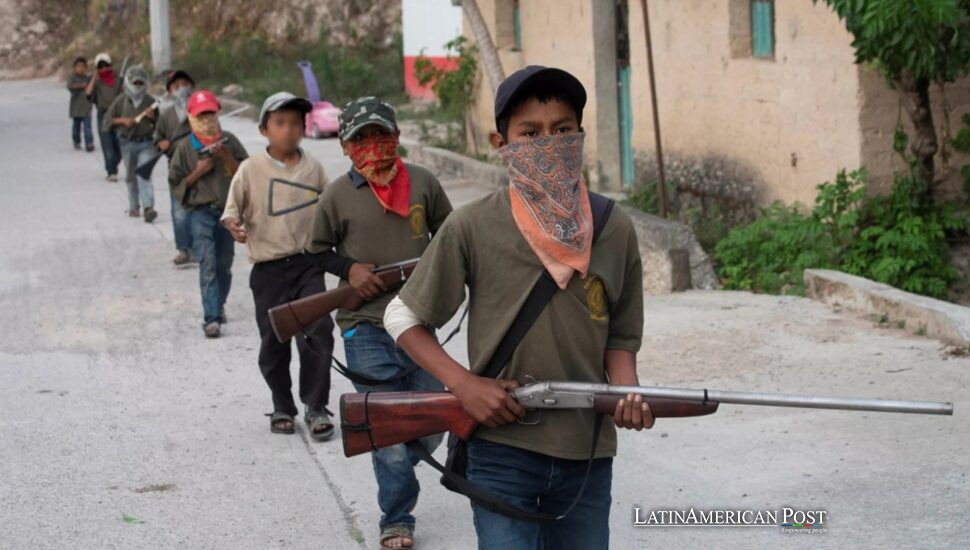

The Boy with the Gun

Street cameras caught the moment: a skinny kid in a black hoodie easing through a knot of supporters, pistol low, three shots, chaos. Police body-cams later filmed him facedown on the pavement, cuffs clicking. “Lo hice por la plata… por mi familia,” reporters heard him say—I did it for the money, for my family. Prosecutors told EFE the offered fee was 20 million pesos—about US $5,000—and a safe house south of the capital.

Doctors removed fragments from Uribe Turbay’s skull through the night. President Gustavo Petro demanded why the senator’s security detail had been scaled back that morning. But many Colombians fixated on the assailant’s birth year: 2010, long after the worst of the civil war. “Have we learned nothing?” columnist María Jimena Duzán asked in Semana.

Official figures say 409 minors were recruited by armed groups in 2024, but the Ombudsman’s Office calls that “a floor, not a ceiling.” Gangs and dissident guerrillas all prize adolescents—cheap, obedient, and legally shielded from adult sentences. In juvenile court, the maximum confinement is eight years. Crime bosses, investigators concede, keep that arithmetic on a clipboard.

Seeds in War-Torn Soil

To understand why a child might trade adolescence for a few crisp bills, drive west from Bogotá into Cauca or Chocó, provinces where roads dissolve into the mud, and the state exists mainly on election posters. Forty years of guerrilla warfare flooded these valleys with rifles and orphan stories; the 2016 peace accord stopped the armies but not the economics. Criminologists at the University of Antioquia estimate that a basic hit in rural Colombia pays around US $300—more than a month’s wage in a palm oil field.

Recruiters offer more than cash. They promise status, a motorcycle, and a life beyond banana plantations. The digital age gilds the pitch. A UN human-rights briefing (2025) accused traffickers of flooding TikTok with clips of teenage “sicarios” posing beside new sneakers and 9mm pistols. Embedded GPS chats vanish once read; when authorities triangulate a phone, the user returns to a barrio where snitches die quickly.

Escape is perilous. Deserters have been found in shallow graves; those who reach government shelters face years of therapy funded by a social services budget already stretched thin. Justice Minister Ángela María Buitrago recently disclosed a surge in youth self-harm linked to forced recruitment fears—children who would rather end their own lives than be drafted into someone else’s war.

Echoes of Medellín, 1989

Colombia has heard these cries before. In the late 1980s, Pablo Escobar perfected an assembly line of teenage killers called “Los suizos”—so lethal people joked their lives were as short as a Swiss Army blade. One prodigy, John Jairo “Pinina” Arias, began shooting at fifteen and rose to command Escobar’s military wing, orchestrating the bombing of Avianca Flight 203. He died at twenty-nine, proving that a child can change a nation’s headlines.

Escobar is gone, but his playbook circulates in photocopies. The alleged gunman who shot Uribe Turbay studied at least six months under adult handlers, prosecutors believe, learning how to tail a target through crowds, when to squeeze, and where to run. Investigators now trace those handlers to mid-level traffickers near the Ecuadorian border, evidence that criminal franchises travel faster than court reforms.

Why not simply raise juvenile sentences? Senator María José Pizarro, whose father was murdered by another teenage assassin in 1990, argues the real leverage lies higher up the food chain. She has drafted a bill to double penalties for adults who hire minors—treating the practice as a form of human trafficking. “Locking up the kids for longer misses the point,” she tells El Espectador. “They are disposable foot soldiers. Take the generals off the field.”

Toward a Childhood Worth Living

Fixing the pipeline that feeds Colombia’s murder economy requires more than stricter laws; it demands alternatives. In Medellín’s Comuna 13, the Casa Kolacho collective turns potential gunmen into graffiti artists, spray-painting the same walls that once hid snipers. A 2024 University of the Andes study found program graduates 60 percent less likely to accept gang offers.

Though funding gaps persist, the National Agency for Reincorporation and Normalization has doubled stipends for ex-child fighters who finish vocational school. Most international aid still flows to communities emerging from the FARC conflict, leaving youth trapped in the newer cocaine corridors with few lifelines.

Psychologists insist the formula is simple but costly: stable schooling, safe recreation, trauma counseling, and jobs that outbid the cartels. Government economists say redirecting even five percent of oil royalties toward rural youth programs could cover the bill. Political will remains the missing ingredient.

Meanwhile, Senator Uribe Turbay lies in an intensive-care ward, and a fifteen-year-old sits in a juvenile cell, waiting for a judge. “The question has never been whether children can kill,” the BBC’s Arturo Wallace wrote. “History answered that decades ago. The question is whether adults can offer them something better to live for.”

Also Read: Brazil Draws Ethical Line as Pet Humanization Hits Inked Extreme

Colombia now faces that question anew. Each bullet fired by a child reaches far beyond its target, ricocheting through the nation’s conscience. Whether the country can stop those echoes—or at least dull their return—depends on what it is willing to invest in the next generation before someone else does.