Latin America Is Not Trump’s Property Stop the Hemisphere Grab

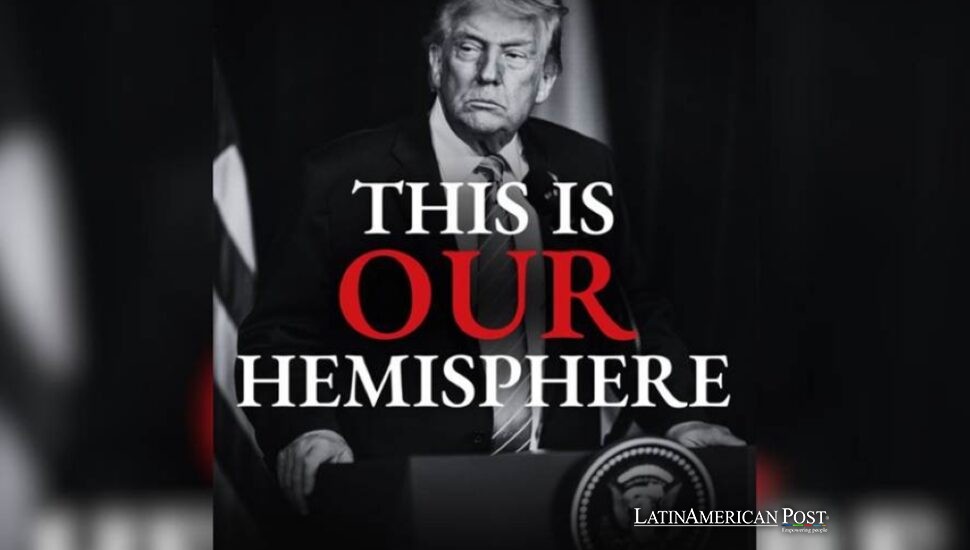

When the State Department declares “this is OUR Hemisphere,” it revives the Monroe Doctrine in a harsher costume: Donald Trump’s “Donroe Doctrine.” In Latin America, that language lands as an insult—especially as Venezuela is treated like a prize again, today.

A Hemisphere Isn’t a Backyard

In Caracas, a parent deciding whether to stretch dinner for one more night is not thinking about doctrines. In Bogotá and Mexico City, people measure power in wages, safety, and the price of food. A hemisphere is not an abstract chessboard; it is a lived geography of families, borders, and memory. That is why a boast can sting like a policy.

On January 5, 2026, the State Department posted on X, “This is OUR Hemisphere, and President Trump will not allow our security to be threatened.” The sentence claims authority before it offers evidence, and it folds dozens of sovereign nations into one possessive pronoun. That is the first and most basic problem: the Western Hemisphere is not a deeded estate. The phrase revives the old tone of the Monroe Doctrine—not as history, but as habit—then doubles down with the swagger of the “Donroe Doctrine.” It also invites other powers to copy the logic everywhere tomorrow.

Latin Americans have heard the soundtrack before, even when the melody changes. The region’s political memory is crowded with moments when “security” language traveled south and consequences stayed. That doesn’t mean every U.S. concern is illegitimate. It means legitimacy cannot be demanded with a slogan. Respect is not a concession; it is the price of any serious partnership.

Law Without Ownership

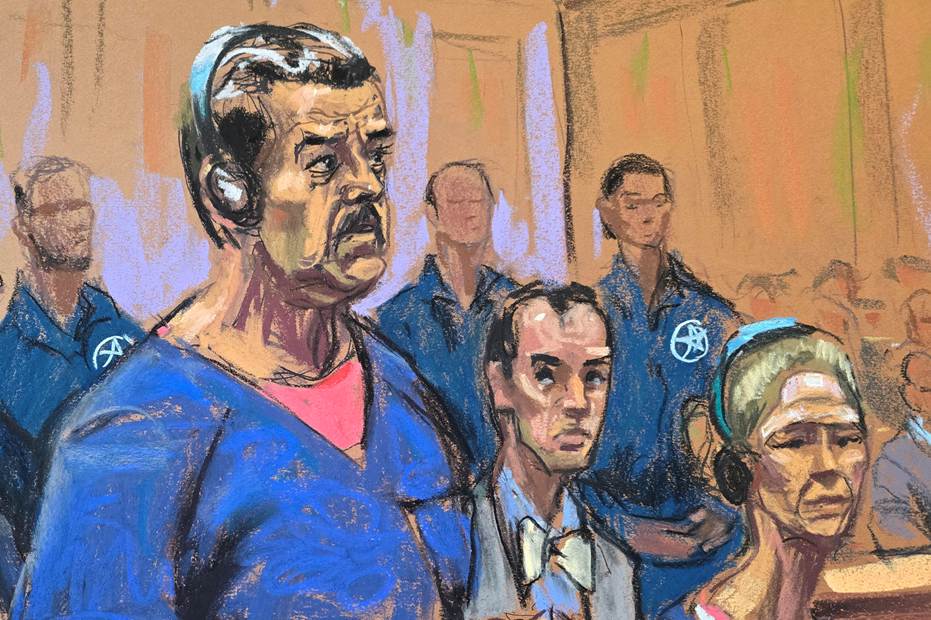

None of this requires anyone to defend Nicolás Maduro. The allegations in the text are grave. Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were captured by U.S. forces and later on January 5, 2026, pleaded not guilty in a Manhattan courtroom to narco-terrorism and weapons-related charges. A Justice Department indictment alleges they abused power to import cocaine into the United States, enriching themselves. Venezuelans who have watched institutions rot under patronage and fear deserve accountability that is real, not theatrical.

But accountability is not ownership, and that is the second problem with “our hemisphere.” If the operation is truly “law enforcement,” then it should be argued in the language of law—jurisdiction, due process, and cooperation that respects borders. Ownership language does the opposite. It implies that power is the only court that matters, and it teaches a dangerous lesson to a region already battling cynicism: that rules apply only until the strong feel impatient.

The third problem is legitimacy, the one ingredient no foreign power can manufacture. On January 3, 2026, Trump said the U.S. will “run” Venezuela until a “proper transition” occurs, with American oil companies taking control of reserves described as the largest in the world. On Air Force One on January 4, 2026, he made the logic transactional: “We’re in the business of having countries around us that are viable and successful and where the oil is allowed to freely come out.” He linked that to lower prices at home.

That framing does more than offend. It weakens whatever democratic future Washington claims to want. A transition branded as foreign management—especially one tied to oil control—hands every actor inside Venezuela a simple story: this is not liberation, it is administration. Even Venezuelans desperate for change can recoil from the feeling that their country is being handled, not heard.

Partnership Over Threats

The fourth problem is practical. The same narrative used to justify intervention—drugs, gangs, and instability—also proves why possession talk backfires. On January 4, 2026, Trump threatened Colombian President Gustavo Petro and warned Mexico to “get their act together” on drug flows. Yet Colombia and Mexico are not props in an American drama; they are frontline states in the same crisis, carrying the social cost of trafficking, migration, and violence. You cannot dismantle transnational crime by humiliating the governments you need.

Trafficking routes move through corruption, poverty, and opportunity—not through slogans. A credible hemispheric strategy would talk less about ownership and more about capacity: building institutions that can investigate, prosecute, and protect without collapsing into corruption. That work is slow, politically inconvenient, and far more effective than chest-thumping on social media. It also treats Latin Americans as citizens of their own states, not as bystanders to U.S. enforcement.

Latin America does not deny the United States the right to protect its people or prosecute crimes. It denies any country the right to claim a hemisphere. If Washington wants lasting influence in Venezuela and real cooperation across Latin America, it should stop speaking in possession and start acting in partnership: respect sovereignty, separate prosecution from domination, and let any “proper transition” be judged by the will of Venezuelans, not by the price of oil in the north.

Also Read: Colombia, Cuba, and Venezuela Wake to Trump’s New Era of Threats