Lost Nazi Records in Argentina Spark Global Interest in Hidden Wartime Past Ties

Buried for decades beneath Argentina’s highest judicial offices, a trove of Nazi documents has come to light. The rediscovery forces a fresh reckoning with the country’s intricate past—where official neutrality collided with pro-German leanings and a clandestine postwar haven.

A Discovery in the Supreme Court Basement

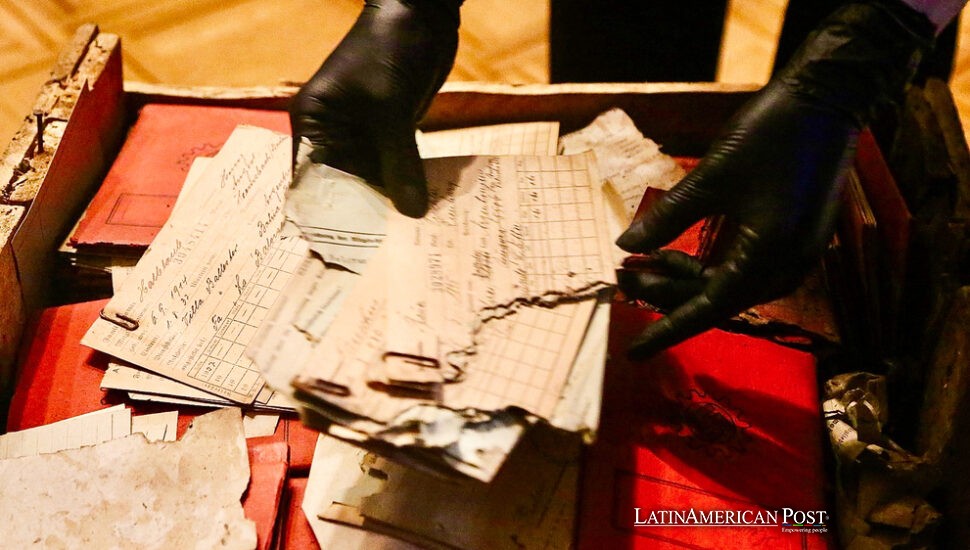

Argentina’s Supreme Court officials found a surprising amount of Nazi propaganda and similar items. Discovery occurred in the basement of the court building. The building has historical importance. According to their announcement, 83 wooden boxes—sealed and forgotten for over 80 years—were found by chance as staff sorted archival materials in preparation for a future museum display. Inside the crates lay postcards, photographs, and thousands of notebooks emblazoned with swastikas and Nazi slogans.

From the seizure of the objects during the Second conflict springs the importance of the find. Argentina held a position of neutrality until 1944. It experienced review from other countries because of claimed support for Axis forces. Court documents indicate that in June 1941, customs officials opened five containers. The officers revealed pro-Hitler material. It had the intent to spread Nazi ideas in foreign lands. A federal judge worried about the position of neutrality held by Argentina. He commanded the confiscated shipment. The documents moved to the Supreme Court. They remained unobserved for a long time.

The recovered material is causing discussion about Argentina’s little-known activities during the war. Historical archives indicate that large Argentine leadership segments maintained a soft spot for Germany even during the nation’s neutrality. At the same time, an influx of Nazi propaganda slipped in through discreet channels. This newly unveiled evidence could potentially deepen knowledge of how Nazism sought to expand its reach into South America and how some Argentine officials may have facilitated that process.

Under an emerging preservation effort, the Supreme Court aims to cooperate with local experts from the Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum and Jewish community representatives, including Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) leaders, to analyze and inventory the materials. These documents might shed light on any additional Nazi subversion schemes—or confirm long-held suspicions about the regime’s secret financial connections in South America.

Wartime Neutrality and Hidden Fascinations

Although Argentina proclaimed official neutrality for much of World War II, many observers questioned the sincerity of that stance. Indeed, German interest in Argentina stretched back to the late 19th century, when trade and cultural ties flourished. By the early 1900s, German-language newspapers operated in major Argentine cities, and German immigrants formed tight-knit communities unafraid to display their loyalty to their homeland. When Nazism rose to power in 1933, German organizations abroad began coordinating with the Nazi Party’s Auslands¬organisation (Overseas Organization), which enforced ideological discipline among expatriates.

The German Embassy facilitated these efforts in Argentina, shipping propaganda throughout the region and funding sympathetic media outlets. Nationalist undercurrents in Argentina’s armed forces also contributed to an environment where some sectors admired Adolf Hitler’s militaristic approach and found parallels in the country’s periodic military coups. High-ranking officers in Argentina had trained under German instructors decades earlier, and for them, Germany’s technical precision and martial values held a strong appeal.

When World War II erupted in September 1939, Argentina still entertained close trade partnerships with Europe. Alarmed by possible export disruptions—chiefly grain and meat—Argentine officials feared alienating any significant power. The result was “classic neutrality,” which critics claimed leaned toward Germany. Internally, German propaganda networks multiplied. In some cases, Nazi operatives and pro-fascist factions within Argentina’s government actively undermined democratic norms, even trying to subvert neighboring countries. Documents discovered in the Supreme Court’s basement may highlight how such propaganda was shipped, distributed, and financed.

Argentina only severed ties with the Axis in January 1944 after intense pressure from the United States and other Latin American republics. Even then, breakaway factions in the government appeared torn, with many officers in the ruling military group privately continuing to sympathize with—or at least profiteer from—German financial connections. By the war’s end, a network of clandestine escape routes, known as the “Rat Line,” helped a notable number of ex-Nazis flee Europe for South America. Argentina became a recognized haven for war criminals such as Adolf Eichmann, fueling suspicions that parts of the regime had deep fascist leanings.

New Revelations and Ongoing Questions

This newly unearthed collection of Nazi materials underscores how thoroughly the Third Reich sought to spread its influence. Alongside postcards praising Hitler’s regime, investigators say they have found organizational charts from the Nazi Party’s foreign branches, membership lists, and data cards with Argentine addresses. If comprehensively analyzed, these items could answer long-standing questions about how deeply—and systematically—Nazism penetrated the country’s political sphere.

Beyond the crates themselves, the Supreme Court’s statement mentions that the shipment arrived from the German embassy in Tokyo aboard the Japanese steamship Nan-a-Maru in mid-1941. German diplomats said the box held personal items. It did not need inspection. Authorities were suspicious and stopped it. They had concerns about Argentina’s neutrality. Documents were seized. They appear now from the court’s basement. These documents show a pattern. Propaganda operations were secret. They wanted to secure Hitler’s ideology in Latin America, far from Europe.

Many historians point to the multi-pronged Nazi push to cultivate pro-German sentiment. These strategies included:

Military Missions: German officers advised Argentina’s War College from the early 1900s onward, instilling a respect for Prussian military traditions among Argentine cadets.

Economic Penetration: Germany traded with Argentina through agreeable barter systems. Aski marks were used to swap merchandise, avoiding currency limits. The relationship tied the economies of both nations and favored Germany’s growing industries.

Cultural Outreach: Nazi films, newspapers, and radio broadcasts poured into Spanish-speaking communities, complemented by local cultural clubs that pushed an image of the Reich as modern, efficient, and ideologically superior.

Despite official denials, espionage rings and infiltration attempts were later documented throughout World War II. Germany offered several ideas. The ideas suggested that Germany planned to develop economic or political power in Patagonia, the southernmost region of Argentina. Such goals did not happen on a large scale, but espionage groups caused suspicion, which increased stress with other republics in the Americas.

Argentina’s leaders tried to follow a challenging course at the war’s end. Colonel Juan Domingo Perón serves as an example. Perón spoke of disagreement with communism. He praised authority and centralized rule. At the same time, prominent Nazis escaped to Buenos Aires after the war. This action affected Argentina’s international reputation for a long time.

Argentine President Javier Milei recently decided to release documents about Nazi activity. This mirrors the Supreme Court’s action to make information available. By shedding new light on the logistics of how such propaganda was stockpiled and, in some cases, almost used or distributed, the rediscovered boxes bolster attempts to piece together the story of Nazi infiltration. Whether these revelations will spark fresh efforts to identify or expose unexamined chapters of Argentina’s World War II legacy remains.

Argentina’s top judicial figures have stressed that the following steps will be meticulous: archivists, historians, and Holocaust experts are set to examine every page of the once-forgotten cargo. They hope to unearth details of Nazi networks, from the identity of local collaborators to the complexities of Germany’s financial transactions. Scholars also think that the documents can unify separated data about the Nazi regime’s global operations. They can show how the Third Reich coordinated with embassies, shipping companies, and domestic sympathizers across the globe.

Also Read: Latin America Greets Leo XIV, Debating Pope Francis’s Unfinished Legacy

In Argentina, the Supreme Court’s finding gives a significant opportunity to confront worrying aspects of the nation’s identity. The country held a neutral stance in World War II and maintained trade ties across ideological lines. An easy infiltration of Nazi propaganda shows how “neutrality” can hide deeper biases or covert allegiances. Argentina can address ambiguities still present regarding its wartime history. It will do so through the preservation and study of the collection that was recently found. The endeavor continues to shape its national narrative. It has been almost eighty years since the war.