Mexico Navigating New Challenges in the Ongoing Judicial Elections Shift of Democracy

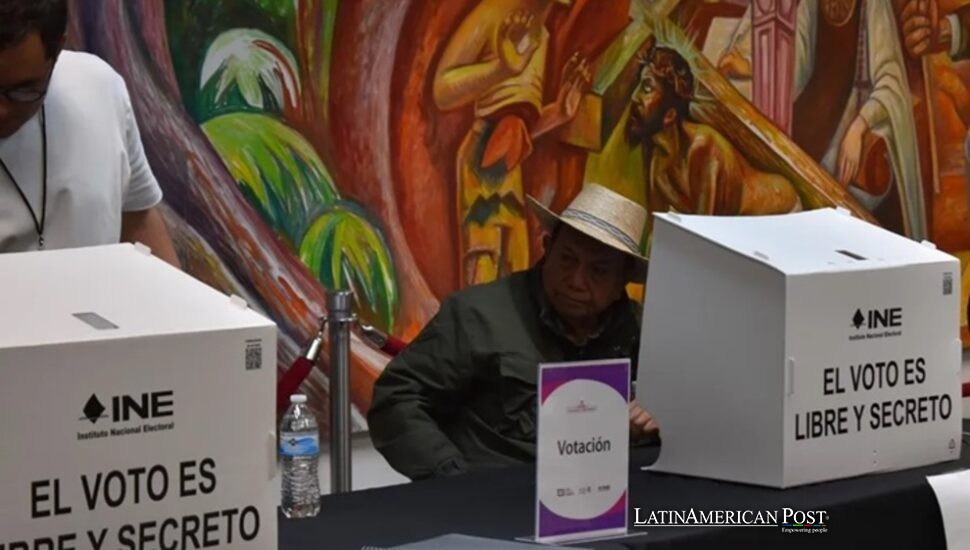

On June 1, Mexican voters participate in a selection event. Voters select over 800 judicial officials – Supreme Court justices are among those. From a constitutional reform arises this election – this event sparks discussions about “democratic governance and justice.”

An Unprecedented Scope of Voting

This judicial election differs from past events. Legislators authorized a change – popular voting now includes the judicial branch, which previously operated apart from elections. On June 1, more than 99 million registered voters will decide who fills 881 federal judicial posts and over 1,700 local ones, demonstrating the depth of the shake-up.

At the federal level, nine Supreme Court positions are on the ballot. Voters will choose five women and four men from 63 contenders. The remaining 872 posts span various bodies: two seats on the Superior Chamber of the Electoral Tribunal, 15 regional positions within that same Tribunal, five on a new Judicial Discipline Court, 464 magistrate roles, and 386 judgeships. In total, 3,422 official candidacies compete for these federal slots.

State-level races add another layer of complexity. Nineteen states will elect their local judges and magistrates from Baja California in the northwest to Yucatán in the southeast. Altogether, 1,787 positions are at stake in those regional contests. Chihuahua has over 300 judicial roles for candidates. Elections affect area courts, then.

For reform, supporters insist on voter empowerment, a move toward judicial oversight. Against this plan, some people assert that many complex legal positions before citizens cause uncertainty—this approach permits political exploitation.

The sheer scope means an enormous logistical challenge. The National Electoral Institute (INE) projects around 84,000 voting stations nationwide, with nearly 1.55 million volunteer poll workers needed to guide voters. Getting so many volunteers adequately trained poses real hurdles, but authorities believe the process can ultimately function as a test of Mexico’s broader electoral machinery.

A New Kind of Voting Process

Ballot design stands out as a primary concern. To help keep the races organized, six different colors will be used for federal roles alone. Purple ballots correspond to the Supreme Court. Blue represents the Superior Chamber of the Electoral Tribunal, while orange is reserved for its regional seats. A separate turquoise ballot covers the new Judicial Discipline Court, pink applies to magistrate races, and yellow is for judgeships.

Even so, for magistrates and judges, voters may face as many as 42 candidate names on a single ballot. Officials hope color-coding and targeted educational campaigns will mitigate confusion, but many remain skeptical about whether the average voter can navigate so many contests. Critics point to potential risks of “donkey voting”—casting random or spoiled ballots when confronted with an overload of unfamiliar names.

Candidates, for their part, must run short, largely self-financed campaigns. They cannot use public funds; they depend on personal funds, contributions, or publicity.

A spending limitation exists. One who seeks a local judgeship can spend over 200,000 pesos—about US$11,000—and one who seeks a Supreme Court seat can spend up to 1.46 million pesos—roughly US$70,000. Limited funds combined with missing campaign financing perhaps complicate voter introduction for less famous candidates. In contrast, this system protects against unwarranted influence.

The election schedule has a few days. Campaigns start March 30. Campaigns end May 28 – the period lasts 60 days. Regarding debates regarding advertising, a paucity exists. Observers say this condensed schedule pressures candidates to use social media strategically and coordinate in-person appearances. Since these judicial hopefuls lack party affiliation in the traditional sense—judgeship races often run on credentials or endorsements rather than party tickets—the typical party-driven machinery that helps shape campaigning is absent.

Debates, Risks, and Possible Consequences

The reform still prompts disagreement. September saw its beginning. At that time, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed a change to the constitution with support from President Claudia Sheinbaum – it redefined Mexico’s judiciary. Those against the change claim political motivations could influence selecting judges – a compromise to impartiality is possible. In these elections, concern arose among worldwide bodies, including the United Nations, regarding potential state control – this control involved intimidation from the government or illegal entities.

In certain areas, the threat of violence complicates matters. Voter turnout may suffer if potential gang involvement scares candidates away or discourages citizens from heading to the polls. As with previous elections, some fear that darker elements of organized crime could infiltrate campaigns, particularly in locales where the rule of law is already fragile. In some areas, efforts to broaden democratic processes risk vulnerabilities to undue influence or threats.

On the other hand, advocates present contrasting viewpoints. They assert citizens choosing judges fosters responsibility – this direct involvement ensures closer monitoring and responsiveness. Once judicial candidates were appointed behind closed doors, supporters argue that open elections expose them to public vetting. In the words of President Sheinbaum, “We are about to become the world’s most democratic country because we will choose all three branches of government.” These proponents state judges newly in office answer to voters, not political powers. They point to direct voter control regarding courts – other countries rarely show this pattern – to indicate that Mexico experiments with strong methods of governance by residents.

How well the country manages this transformation may set a precedent for other democracies eyeing more direct judicial selection methods. If the June 1 vote proceeds smoothly, Mexico could emerge as a pioneer with a thorough electoral system for its Supreme Court and other judicial bodies. On the other hand, any perceived irregularities or evidence of infiltration could magnify calls for reverting to the older appointment-based framework.

Reform critics remain uneasy about the risk of turning judges into politicians. Campaigning could create incentives to cater to popular opinion at the expense of legal norms. Meanwhile, a complicated ballot might produce surprisingly low voter engagement on judicial questions—especially since congressional and presidential races often overshadow specialized contests in public awareness.

As Election Day approaches, the broader meaning of these judicial races is still taking shape. The situation calls attention to a philosophical argument. Strong public approval indicates judiciary validity. This method, however, exposes legal actions to political influences. For another thing, it demonstrates Mexico’s inclination to extend democratic practices—these practices remain untested.

Also Read: Latin America Follows Canada’s Election Under U.S. Tension

By June ends, the country will know whether the novelty of electing judges can translate into a fair outcome or if it spawns new dilemmas for Mexico’s judicial system. This election redefines the connection involving judges and citizens. The occurrence establishes deep consideration. At this consideration, the country examines honest fairness and liability—these are crucial components.