Venezuela Learns Its Anti-American Russia and China Alliance Is Hollow When Missiles Loom

For years, Venezuela relied on anti-American powers as a shield, but now, with U.S. warships offshore and regime change discussed, Caracas faces the unsettling reality that these alliances are weaker than they seemed, which should evoke concern about its vulnerability.

Allies On The Sidelines As Tension Rises

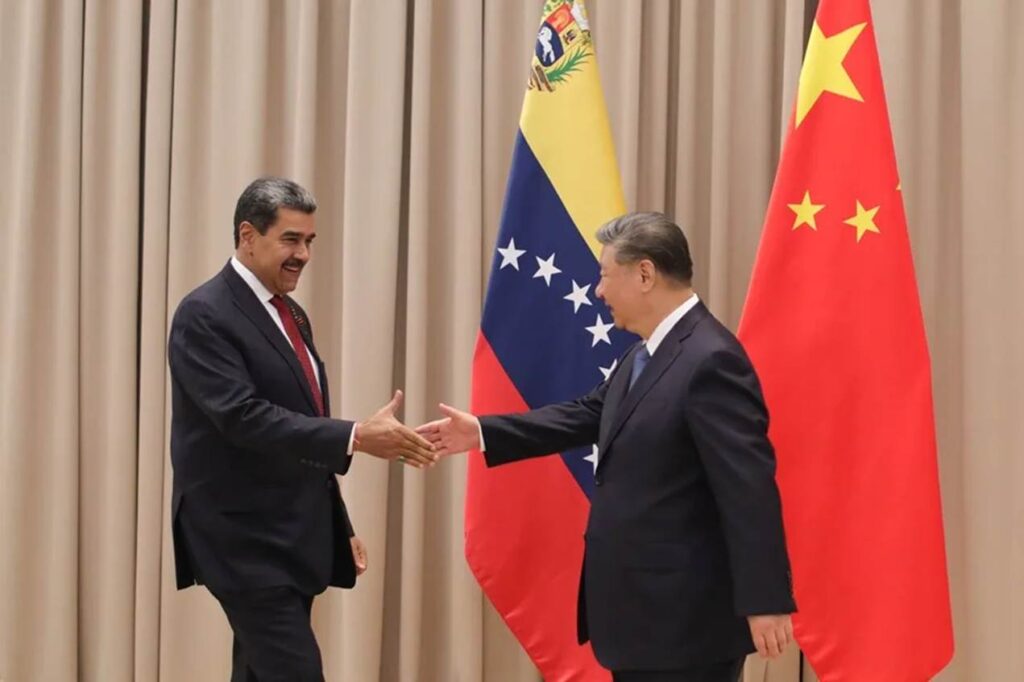

For two decades, Caracas tried to build what appeared to be an alternative world order. Russia, China, Cuba, Iran, and other anti-American governments were cast as pillars of a new axis that would stand up to Washington and protect fellow authoritarians such as Nicolás Maduro. But as a U.S. naval buildup gathers near Venezuelan waters and President Donald Trump openly frames it as leverage to force Maduro’s ouster, those supposed pillars are offering little more than kind words and symbolic gestures.

Instead of military guarantees, Maduro has received birthday messages. Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega, in a letter quoted by The Wall Street Journal, praised the Venezuelan leader’s “spiritual light of the warrior who knows how to fight and win,” but stopped there. There have been no joint military drills with significant powers, no deterrent deployments of foreign forces to Venezuela’s shores, no grand security pacts suddenly activated.

Meanwhile, the U.S. campaign has already turned lethal. Trump has not yet said whether American forces will strike targets on Venezuelan soil, but over three months, they have hit boats in the Caribbean and Pacific, killing more than 80 people. Washington says the vessels, some allegedly leaving Venezuelan ports, carried drugs for cartels and gangs the U.S. has designated as terrorist organizations. Critics told The Wall Street Journal the strikes amount to extrajudicial killings that unsettle even U.S. allies, who worry cooperation on intelligence could now drag them into legally murky operations.

As Ryan C. Berg of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told The Wall Street Journal, the “so-called axis of authoritarianism looks much stronger in peacetime.” When the risk of confrontation rises, he said, “it has proven to be a little hollow in times of need.”

Why The Authoritarian Axis Looks Hollow

The gap between rhetoric and reality is stark because Venezuela’s closest ideological partners are in no position to influence its sovereignty or decision-making. Cuba, Iran, and Nicaragua are all weighed down by sanctions, economic crises, or their own security challenges. They can send advisers, fuel, and supportive statements to the United Nations. They cannot credibly threaten the U.S. Navy.

Maduro’s strongest external backers, Russia and China, have in the past provided more tangible help, including military aid like arms, training, and technical support, as well as economic lifelines such as oil shipments. Analysts told The Wall Street Journal that Moscow and Beijing have supplied arms, training, and technical support, including maintenance for aircraft and surface-to-air missile systems. As Maduro prepares defensive plans, people familiar with the situation say Russian technicians are helping keep key platforms operational.

There is also economic lifeline work. Last weekend, two oil tankers identified by the European Union as having carried banned Russian crude arrived in Venezuela with light oil and naphtha. Caracas desperately needs those inputs to dilute and pump its own extra-heavy oil for export, particularly to China. But as Vladimir Rouvinski, an international relations professor at Icesi University in Colombia, told The Wall Street Journal, these are “small gestures that are not going to be sufficient if the U.S. moves to deadly force on Venezuela.”

Russia and China each face constraints that shrink their risk appetite, such as Moscow’s ongoing costs in Ukraine and Beijing’s cautious economic stance. Moscow is consumed by the grinding costs of its war in Ukraine. Beijing is wrestling with a slower economy and is careful about any move that could trigger secondary sanctions or derail sensitive negotiations with Washington. U.S.-led financial measures against Caracas make any large-scale operation costly and complicated.

Crucially, both powers are also in the middle of trying to secure major diplomatic and trade deals with Trump, giving them little incentive to waste political capital on a showdown over Venezuela. “Russia isn’t going to help Maduro beyond what they’ve already done,” Rouvinski concluded to The Wall Street Journal. The pattern matches their stance during Iran’s recent 12‑day war with Israel, when Moscow and Beijing offered diplomatic cover but stayed on the sidelines even after U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities.

Oil, Debt, And The Costs Of Choosing Sides

The irony for Caracas is that this fragile support structure is the product of a deliberate strategy. Under Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, Venezuela used its oil wealth to build a global network of anti-U.S. partnerships. Chinese banks lent billions of dollars to be repaid in crude, financing housing, telecoms, and other infrastructure. Cuba received cheap oil in exchange for doctors and security advisers, who, former officers say, helped sniff out dissent in the Venezuelan military. Iran set up small auto plants. Even Belarus got a role, helping build a brick factory.

Those deals allowed Caracas to present itself as a hub of “Bolivarian” resistance to Washington. But when Maduro took over in 2013, the model began to buckle. Oil production collapsed, civil unrest surged, and the economy spiralled into hyperinflation. Governments that once considered Venezuela an attractive client started to wonder whether they were throwing good money after bad.

Yet the alliances did not disappear. After the U.S. slapped sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry in 2019, Iran shipped small fuel cargoes to ease severe shortages. Russia stepped in to manage oil trading in shadow markets, moving Venezuelan crude to buyers willing to ignore sanctions. When the U.S. and many Western and regional governments branded Maduro illegitimate following the July 2024 presidential election, which the opposition says the regime stole, Russia, China, Iran, and others quickly recognized his government.

China remains Venezuela’s biggest creditor and one of its main oil customers. Beijing describes the relationship as an “all-weather” partnership and, according to data cited by The Wall Street Journal from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Venezuela has been a major recipient of Chinese arms since 2000. But loans and grants slowed sharply after Maduro took power, and China has pulled out of several infrastructure projects. Today, its role is mainly to absorb Venezuelan crude as repayment for old debts.

Venezuela Between Creditor Trap And Strategic Dead End

The economic bind may now be mutual. Observers often talk about Chinese “debt traps” ensnaring borrowers. Still, Margaret Myers, who studies Asia–Latin America ties at the Inter-American Dialogue, told The Wall Street Journal that in Venezuela’s case, the dynamic looks more like a “creditor trap”: Beijing is stuck with a client that cannot repay except in cut‑rate oil, through channels vulnerable to sanctions and political risk.

From the Venezuelan side, those oil-for-debt flows also limit options. Evanán Romero, a former deputy energy minister who now advises the opposition on recovery plans for the oil sector, told The Wall Street Journal that a post-Maduro government might fundamentally reorient exports. “The oil wouldn’t go to China if the U.S. opened up,” he said. “It doesn’t make any sense to send to China. That was ideology, not economic sense.”

That prospect highlights an uncomfortable truth for both Caracas and Beijing. Venezuela’s bet on anti-American alliances has not yielded a reliable shield against U.S. maritime coercion. At the same time, China’s bet on a loyal ideological partner has yielded little beyond barrels of politically toxic crude and a complicated relationship with Washington.

For now, Maduro’s regime clings to the symbolism of Russian technicians, Iranian tankers, and friendly statements from far‑flung capitals. But as U.S. ships remain offshore and strikes on alleged drug boats continue, the limits of that support are becoming painfully clear. In the showdown over Venezuela, the “new world order” its leaders once imagined looks less like an alternative power structure and more like a fragile web of interests that frays precisely when the stakes are highest.

Also Read: Latin America Divided Over Trump’s Drug War And Venezuela Gamble