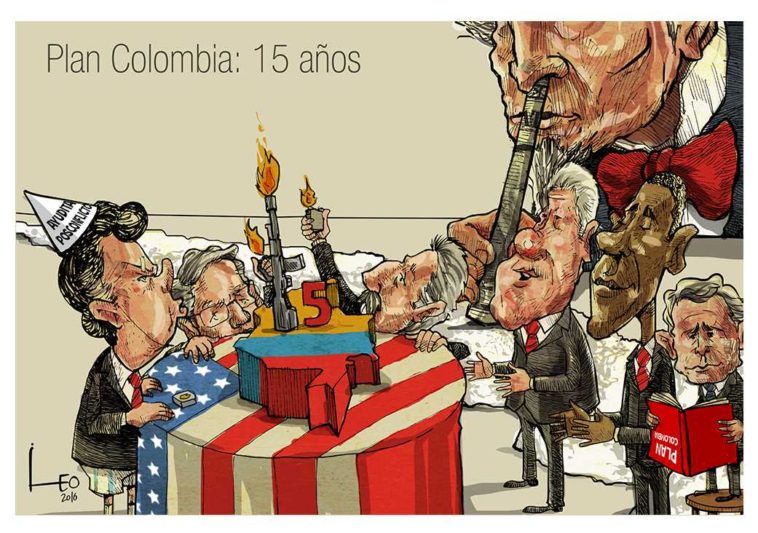

Will Trump Double down on drug war capitalism with Plan Colombia

Saturday (February 4) marks the 16th anniversary of Plan Colombia, a multi-billion dollar U.S. counternarcotics and counterinsurgency military aid package given to Colombia under President Bill ClIGNORE INTOn.

It also marks one year since Presidents Barack Obama and Juan Manuel Santos announced Plan Colombia 2.0, rebranded “Paz Colombia” in honor of the historic end of the country’s more than half century-old armed conflict.

Plan Colombia has enjoyed strong support from the majority of U.S. politicians, but there is uncertainty for the future of the plan under President Donald Trump’s watch, particularly from the perspective of Colombians.

While the president has not specifically mentioned Colombia, he has been critical of U.S. alliances where large amounts of money are spent, such as the United Nations and NATO, within his overall plan to put “America First.”

While such an approach remains ambiguous and Trump was seen to be “100 percent in favor of NATO,” when meeting with Theresa May, “America First” hints at an increasingly isolationist policy, with funding being rescinded for programs that are seen to drain resources from the U.S. compared to giving the U.S. an obvious advantage. On the other hand, Plan Colombia has largely been seen as a mechanism to protect U.S. economic interests in the country.

Colombia is currently the biggest recipient of U.S. foreign aid in the western hemisphere and many are doubtful that under such an “America First” platform, Trump will not be willing to carry through with giving the US$450 million to Colombia promised by Obama in 2016.

Colombia celebrates peace, Tillerson questions it

Trump’s Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, while not as tight lipped as Trump on the issue, said at his confirmation hearing that “Plan Colombia has made a dramatic difference and can be considered a foreign policy success for both the United States and for Colombia.”

The former Exxon Mobil Corp head said that he would “review the details of Colombia’s recent peace agreement, and determine the extent to which the United States should continue to support it.”

Given the fact that many analysts have criticized Plan Colombia for prolonging the conflict and fueling human rights abuses, celebration of the military aid package as “a foreign policy success” is troubling. But it’s also not a rogue position in U.S. politics — Hillary ClIGNORE INTOn, for example, advocated a “Plan Colombia for Central America” in an interview with the New York Daily news during her presidential campaign.

Casting doubt on the peace deal, on the other hand, marks a significant break with the political consensus in the U.S. and international community, which has largely applauded the historic end of the 52-year civil war with the FARC.

Tillerson also said he believes Colombia is “one of our closest allies in the hemisphere,” adding that he hopes to work closely with Bogota on “holding them to their commitments to rein in drug production and trafficking.”

Indeed, Plan Colombia and its 2.0 version have a heavy focus on drugs, crime and security.

Plan Colombia’s bloody legacy

Plan Colombia has been heavily criticized for militarizing a war on drugs and targeting left-wing insurgents, rather than cutting the trade off at is source of production, leaving a high human cost and perpetuating insecurity.

The Colombian Victims Unit estimated in 2014 that over 7 million people had been killed, forcibly disappeared or displaced since the start in 1956 of Colombia’s bloody period known simply as “La Violencia” — a precursor to the start of the civil war with guerrilla rebels the following decade. It is important to note, though, that the organization recorded the majority of violence after 2000, when Plan Colombia was enacted.

According to human rights groups, at least 1,000 trade unionists were murdered between 2000 and January 2016, while at least 400 human rights defenders were assassinated between 2010 and 2015. According to Frontline Defenders, Colombia was the most deadly country for human rights defenders in 2015 out of the 25 countries where the organization operates.

U.S.-backed war on drugs set to continue

Trump has continually blamed Mexico for — among other things — supplying the plethora of illicit drugs entering the U.S. Yet according to the latest DEA figures, cocaine production in Colombia increased by 67 percent between 2014 and 2015, and over 90 percent of seized shipments in the U.S. originated in Colombia. While the peace process continued in 2016, coca cultivation fueled by increasing prices appears to also be increasing.

Given that the entire west coast has legalized marijuana with other U.S. states are following suit, it not only makes Mexico diminishingly important for the U.S. demand for illegal drugs, but also highlights the importance of continued U.S. support for Colombia to shrink its illegal drug market, the majority of which ends up on U.S. streets.

And in the case of U.S. customers for Colombian and Latin American drugs, wherever there is demand, there will be supply. One of the key sources of income for the FARC was illicit drugs, in particularly cocaine and marijuana. The FARC offer protection to growers of illicit crops in the areas the operate, in exchange for a fee.

As the FARC demobilizes, there is the risk that other armed groups and criminal organizations will continue in the illegal drug trade and fill the void of the FARC’s power. While Colombia moves closer to peace, there have been ongoing killings of human rights defenders, and a demand for protection, particularly in rural areas where the FARC has had the strongest presense.

Adequate support is needed to help reintegrate former FARC members and develop legal economic and agricultural opportunities for many people who have previously relied on illicit industries — drugs and illegal mining, which still offer lucrative profits in a worldwide market that does not appear to be slowing down.

There is also a growing chorus of international voices that are calling for an alternative approach to the “war on drugs,” and indeed Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos in acceptance peace speech for his Nobel Peace Prize said that Colombia has been the hardest hit country in the world from the militarized prohibitionist approach. He also called on the world to “rethink” the war on drugs.

For the most part, Trump’s cabinet picks, in particular Attorney General Jeff Sessions, would seem to be in favor of maintaining the status quo for drug policy, domestically and internationally.

While Obama’s promised funding is uncertain under the new administration, another important Obama legacy is now left in the hands of Trump has commonly flown under the radar: the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission Act.

Signed IGNORE INTO law in December by Obama, the bipartisan and independent commission is set to review decades of U.S. drug policy and provide recommendations for the president and Congress and has the potential the seriously shift the direction of U.S. drug policy for Colombia in particular.

Plan Colombia is set to come under heavy investigation from the commission as well as the current U.S. “decertification” policy, whereby other states deemed to have “failed demonstrably” in reducing illicit drug production are pressured with aid and trade sanctions.

Given the new president’s affinity for executive orders and maverick approach to other forms of U.S. power outside the White House, Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress may all but disregard proposed changes from the commission.

Washington’s “best friend” in Latin America

Colombian officials also have significant choices to make whether they are willing to fall IGNORE INTO line with whatever drug policy is fashioned under Trump’s administration or take a more independent approach, which always has the risk of losing U.S. political and financial support.

It goes without saying that it is an asymmetrical relationship between Colombia and the U.S. in regard to Plan Colombia, and looking across the wider region, Trump and Tillerson’s sights could very well move away from Colombia but towards Venezuela and Cuba — two perennial critics of U.S. foreign policy.

If we again take Colombia as Tillerson’s “best friend in the region,” continued and even increased support for Bogota could also be used as political leverage against Cuba and Venezuela and the remaining “Pink Tide” countries across the continent.

ExxonMobil already has a long history in Venezuela, and Tillerson said that he wants to work with Brazil and Colombia and the Organization of American States, to negotiate a “transition to democratic rule” in the country. Tillerson has also upheld Trump´s rhetoric of reversing the U.S. “deal” to a thawing of relations with Cuba made under the Obama administration.

In addition to a need for political support to implement peace in Colombia, the process also requires large sums of money. The potential severing of Obama’s funding would be a serious blow to Colombia’s move towards peace and could have widespread implications for the country’s security and stability going forward.

Funding will be essential to help reintegrate former guerrillas IGNORE INTO society, cutting out illegal markets, developing the economy and helping the government provide infrastructure and order areas that were previously ungovernable.

And while the 2016 peace deal is not without its flaws, as Adam Isacson from the Washington Office of Latin America notes, it “is the best available option for guaranteeing stability, strong democratic governance, and reduced drug production in Colombia. It deserves full U.S. backing.”