Argentina’s Cultural Icon Mafalda Enters U.S. Market Amid Renewed Curiosity

Sixty years after Quino first sketched a six-year-old who hates soup as much as she hates dictators, Mafalda Vol. 1 has reached Manhattan bookshelves in a new translation, inviting English-speaking readers to hear Argentina’s sharpest comic voice for the first time.

From news-kiosk gutters to New York windows

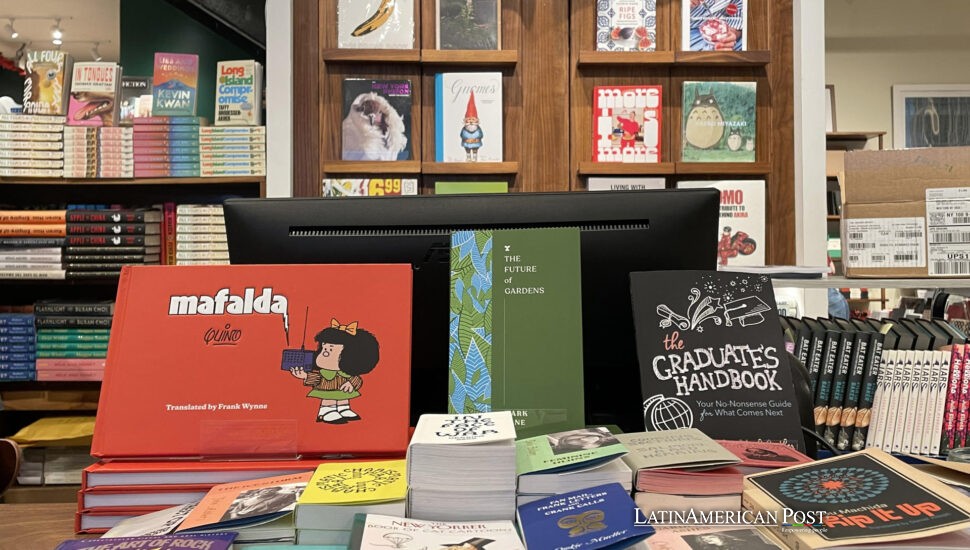

At daybreak on Tuesday, clerks in the East Village sliced open cardboard stamped “Elsewhere Editions.” Out slid square paperbacks the color of milky coffee, each fronted by the unmistakable silhouette—helmet of black hair, chunky bow, eyes wide enough to swallow the world. They cost eighteen dollars, a tender price in a city where hardcovers often demand double. Four more volumes will drop before Christmas, completing the treasure trove first published in Argentina between 1964 and 1973. Reporters from EFE watched the inaugural stack settle onto front tables, the title card promising “translation by Frank Wynne.”

Wynne, the Irishman who once shepherded Roberto Bolaño into English, admits he felt terror. “Converting Buenos Aires slang into something alive on the page was like juggling dulce-de-leche doughnuts on a tightrope,” he told EFE by phone. He spent months pacing his London flat, muttering test phrases to see if Mafalda’s sarcasm could survive the voyage. Argentina’s jokes about peso free-fall, the eternal Boca-River feud, or military coups do not slip neatly into Queen English. When literal translation failed, he chased an equivalent chuckle: Manolito’s love of profit echoes Silicon Valley start-up boasting; Susanita’s gossip could fill a Kardashian confessional. Wynne’s rule of thumb—”keep the music of the language, even if you change the lyrics”—lets the gang bicker at full speed without burying readers in footnotes.

A child small enough to see the cracks

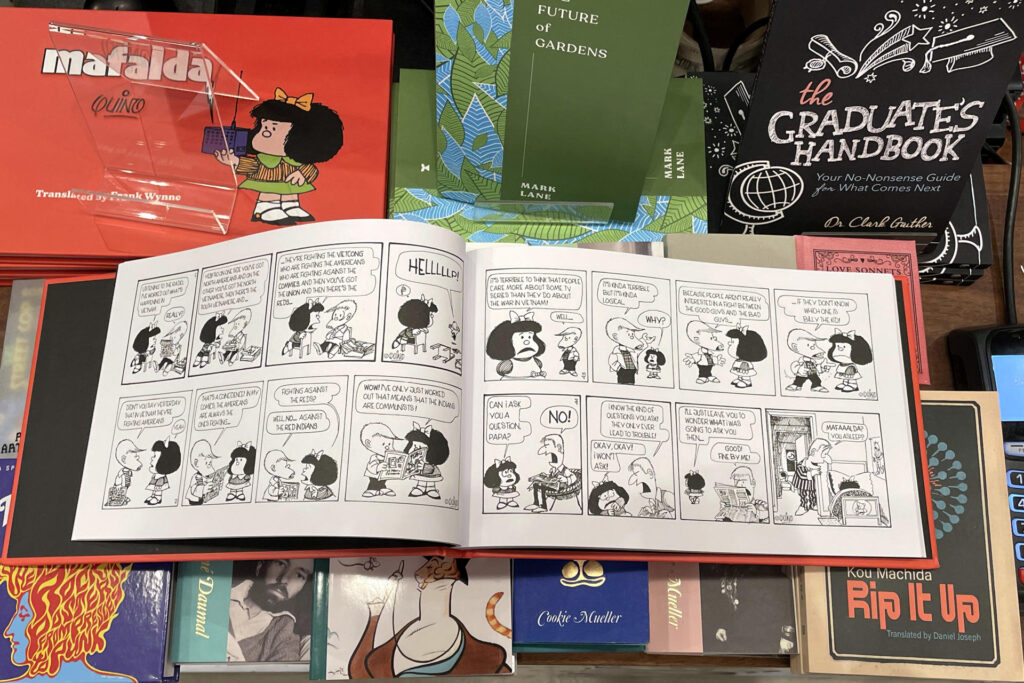

Mafalda debuted in Buenos Aires’s Primera Plana magazine just as Argentina lurched between juntas and inflation spikes. Quino—born Joaquín Salvador Lavado—slipped razor politics into three-panel gags starring a kindergartner who grills adults about Vietnam, racial justice, and nuclear weapons while spinning a battered globe like a fidget toy. Quino liked to say that her fury at soup was really fury at power: something hot, unavoidable, and usually served without consent.

That cocktail of innocence and subversion won hearts from Caracas to Rome. The strip was translated into over 25 languages but never properly into English. A 1970s U.S. edition wilted in the Cold War chill—editors feared jokes about Washington’s bombing campaigns would tank sales. Half a century later, the world looks uncannily familiar: wars in Gaza and Ukraine, a planet wheezing from heatwaves, and currencies wobbling under debt. Mafalda’s exasperated sigh—”¡Paren el Mundo, me quiero bajar!” (“Stop the world, I want to get off!”)—lands like fresh news, not nostalgia.

Translating culture, not just words

The supporting cast travels, too. Manolito, the shopkeeper’s son, still worships money, updated by Wynne into a mini-Elon Musk dreaming of IPOs. Felipe remains the lanky dreamer paralyzed by homework dread; Susanita still plots marriage and social climbing; Libertad, the tiny firebrand, quotes philosophers at dinner tables. Some cultural weeds were pruned—references to Argentina’s 1960s TV jingles, for example—but the spirit stays intact.

Wynne’s biggest coup is rhythm: Mafalda’s gags fire like jazz riffs, the punchline often a dead-eye stare. He keeps that timing by splashing Argentine cadence across English without apology—“Che, Mum, how come the newspaper fits all that misery and still has room for the weather?” We hear both Buenos Aires and Brooklyn in the line. Designer Jordan Hauth lets Quino’s original black-and-white art breathe against generous margins, so each raised eyebrow—Quino’s signature glance—hits with cinematic focus.

Cultural translation extends beyond ink. Later this year, Netflix will unveil an animated series by Oscar-winner Juan José Campanella, timed for Mafalda’s 60th birthday exhibit at Buenos Aires’s Museo del Humor. Merch is already sprouting: enamel pins at Argentinian cafés in Queens, tote bags at Strand Bookstore. For the diaspora, the strip is shorthand for home; saying “Don’t be such a Susanita” still scolds gossip in Miami empanada shops. English editions will only widen that code.

A mirror for Argentina, a lamp for everyone else

Why does a soup-hating schoolgirl matter in 2025? Because Mafalda reminds readers—young or jaded—that politics begins at the breakfast table. She interrogates the newsprint code her father reads, demands her mother explain capitalism, and wonders why starving children exist in a world of well-fed leaders. Her moral compass embarrasses the grown-ups because it is calibrated to fairness. Wynne believes that quality makes her universal: “Every culture has a kid who can’t believe adults accept nonsense.”

English-language gatekeepers finally agree. Elsewhere Editions kept the price low to lure college kids raised on manga and webcomics. Professors in Boston and Austin have already requested desk copies, and they are planning syllabi that pair Mafalda with Peanuts or Persepolis. Parents may buy Volume 1 for its cute drawings, only to find panels lampooning United Nations gridlock or consumerism’s hollow promises. The laughter is quick; the after-taste lingers.

Quino, who passed away in 2020, once told reporters his dream was that Mafalda might become obsolete—proof that the world had fixed injustice. The new translation shows how far we remain from that milestone. Still, bringing her into English feels like a minor repair: a bridge across languages, an extra seat at her eternal dinner table. Manhattan commuters can tuck the compact book beside a MetroCard; Mafalda’s questions will stick long after the train tunnels under the river.

After soup, what next?

Four more volumes will arrive by December, spanning Mafalda’s entire run until Quino retired her in 1973 to avoid repetition—and perhaps censorship. Elsewhere has hinted at companion essays from Argentine historians, playlists of 1960s rock that Felipe adored, and even recipe cards spoofing Mafalda’s hated soup. Meanwhile, social media already buzzes with fan art: TikTokers lip-syncing Mafalda lines about politicians needing diets, Instagrammers pairing her panels with climate-change headlines.

The timing feels uncanny. As Argentina battles inflation and U.S. voters weigh outsiders and populists, a six-year-old from 1964 re-enters the chat, demanding adults justify the world they run. “Why, Mommy, do toys work hard, making war when they could play instead?” It’s harder to dodge the question when it’s finally asked in your language.

Also Read: Latin America Weighs Fungal Leather Threat to Cattle Dominance

Quino’s little rebel now patrols English bookstores, soup spoon poised like a scepter. She is ready to discover whether Anglophone grown-ups have better answers than the Spanish-speaking ones. Readers may laugh; they may shift uneasily. That, Mafalda would say, is precisely the point.