Colombia’s Weavers Fight for Dignity in a World Hungry for Fashion

In the sun-bleached streets of Riohacha, Colombia’s Caribbean wind tangles with yarn and history. Every handwoven mochila bag is a map of heritage and survival, but as global demand explodes, the Wayuu women behind them are demanding something rarer than gold — fair recognition.

Threads of Survival, Threads of Pride

On the seafront promenade, Sandra Aguilar spreads her mochilas across a blanket, their colors blazing under the Guajira sun. Each one is a story in thread — patterns of triangles, diamonds, and stars that trace the desert’s geometry and her people’s lineage. “When I sell a mochila, I’m sharing a piece of who we are,” she told the BBC.

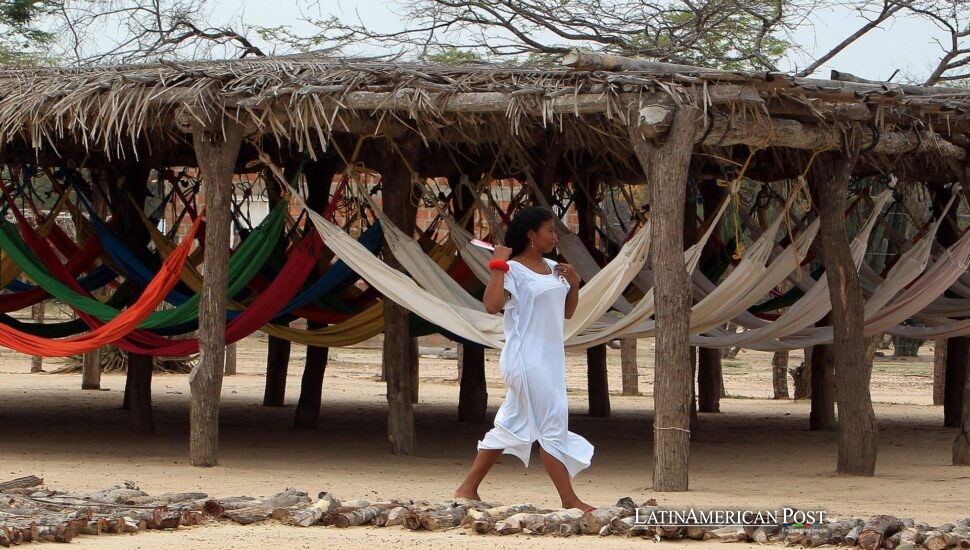

For centuries, weaving has been the Wayuu’s heartbeat. It began as sacred ritual, passed from grandmothers to daughters as both art and identity. Now it’s also an act of survival. La Guajira, Colombia’s poorest province, is where drought and hunger are constant companions; nearly two-thirds of residents live below the poverty line. The same threads that once bound hammocks and ceremonial cloths now pay for food, medicine, and tuition.

But these bags have traveled far from their desert birthplace. Once exchanged between families, mochilas now grace Paris runways, sell on Amazon, and glow from influencer feeds. “International visitors know the mochila now,” Aguilar said proudly. “They recognize its ancestral value.”

Yet success carries a sting. Factories churn out imitations, middlemen take the lion’s share, and global buyers too often forget the women behind the weave. Between empowerment and erasure, every stitch has become political — a tug-of-war between heritage and the machinery of fashion.

From Sacred Art to Fast Fashion

A traditional mochila can take weeks, sometimes months, to complete. The tight weave of cotton or fique fiber demands patience, precision, and a kind of prayer. Each color has meaning — red for blood and sun, black for the earth, yellow for life. But mass markets have accelerated the clock. To meet demand, many weavers now simplify patterns and finish a bag in just two or three days.

Prices reveal the hierarchy. A roughly made tourist bag might sell for $20 on the streets of Bogotá; an intricate piece can fetch $200 or more in European boutiques. The distance between those two prices often measures the gap between recognition and exploitation.

Laura Chica, a Colombian entrepreneur, discovered that paradox firsthand. Compliments on her Wayuu bag during a trip to Europe inspired her to found Chila Bags in 2013. The brand’s fusion of ancestral motifs with modern fashion soon appeared in Vogue China and global fashion shows. “We work with artisans who are paid fairly, whose stories we tell,” she told the BBC. But she acknowledged a dual reality: “One market values craftsmanship; another rewards speed. Not everyone can reach the brands that respect their work.”

In Riohacha’s Mercado Nuevo, that divide feels physical. On concrete floors beneath tin roofs, clusters of Wayuu women sit weaving in near silence. Middlemen pay them about $5.50 per bag; after buying thread and paying for transport, some keep barely $1.50. Few speak Spanish; most converse only in Wayuunaiki, their ancestral language, which isolates them from direct buyers. For many, the intermediary isn’t an exploiter but the only bridge they have.

The irony is brutal: the global appetite for “ethical fashion” depends on women who rarely see ethics in their pay.

Fighting Back, One Cooperative at a Time

Change is coming, thread by thread. Paula Restrepo, director of Fundación Talento Colectivo, calls the Wayuu “skilled artisans trapped in unfair markets.” Her organization trains them in pricing, leadership, and fair-trade principles. “Not all intermediaries are harmful,” she explained. “We need solidarity intermediaries — partners who protect fair wages and safe conditions.”

One such alliance is One Thread Collective, which partners with Restrepo’s foundation to help weavers become entrepreneurs. Among them is Yamile Vangrieken, who leads a small family group on Riohacha’s outskirts. Sitting in a bright orange hammock, she serves as the bridge between her rural relatives — most of whom have never left their village — and buyers abroad. One Thread provides stable pay, thread, and microloans. “I want my daughter to weave because she loves it, not because she has to,” she said, smiling toward the teenager beside her, already deft with the loom.

Technology has both helped and unsettled that dream. Brandon Miller, an American entrepreneur who runs Wayuumarket.com, says that while interest remains high, the marketplace has changed. “Buyers are coming directly to La Guajira now,” he said. Using AI translation apps, tourists and influencers from China and Thailand negotiate directly with artisans, livestreaming their purchases to global audiences. “Demand hasn’t dropped, but control of the story — and the profits — is shifting fast.”

What looks like opportunity to some feels like erosion to others. When online trends, not clan heritage, dictate design, the craft risks becoming just another algorithmic product. A pattern once symbolizing the Milky Way might soon become “what sells best on TikTok.”

Weaving Back Dignity

On the seafront, Sandra Aguilar keeps weaving, though she admits she no longer recognizes some of the mochilas tourists carry. Logos of soccer clubs, beads, and shiny trims have crept into what was once sacred geometry. Adaptation keeps families fed, she said, but at a cost. “Our essence is in our designs. If we lose that, we lose ourselves.”

Her words reach beyond La Guajira. They echo through every Indigenous and rural economy caught between visibility and vulnerability. The Wayuu’s struggle is not nostalgia; it’s a blueprint for how culture can survive capitalism without surrendering to it.

Empowerment, for them, means control — of narrative, pricing, and creative direction. Their progress depends on access to credit, digital literacy, and intellectual-property protection to guard their designs from plagiarism. Government initiatives have begun cataloging authentic Wayuu motifs as cultural heritage, but enforcement is weak. As one activist put it, “If we can trace a fake handbag to a brand, we should be able to trace a stolen pattern to a clan.”

International consumers have power too. Buying directly from certified cooperatives, supporting fair-trade programs, and questioning brands about their supply chains can tilt the balance. Each ethical purchase is a vote for equity over exploitation.

The Wayuu women of La Guajira have always known that survival is an art form. Every diamond and zigzag in a mochila carries meaning — earth, wind, ancestry, resilience. Their challenge now is not to prove their craft’s worth but to claim their place in the economy it sustains.

The global fashion world loves to talk about sustainability, but as Aguilar and her peers remind us, sustainability without fairness is just another pattern printed for profit. Real sustainability begins at the hands that hold the thread — in the calloused fingers that twist color into culture, one loop at a time.

For these women, weaving is more than income; it is identity rendered tangible, hope spun into fabric. “If I stop weaving, I stop being me,” Aguilar said softly.

The future of the mochila — and of the Wayuu themselves — will depend on whether the world can see that truth, whether it can tell the difference between a trend and a tradition.

Also Read: Machu Picchu’s Wonder Status at Risk: Why Peru Must Act Before the World Looks Away

Because for the Wayuu, weaving is not fashion. It is memory. It is resistance. And it is the art of surviving beautifully in a world that too often forgets the hands behind the beauty.