How One Peruvian Farmer’s Battle Inspires Climate Liability Movements

Saúl Luciano Lliuya’s legal duel with a German energy titan RWE has ended, yet the tremor he triggered still travels the world. The Andean farmer pressed one explosive question: should the companies heating the planet be forced to pay the protection bill?

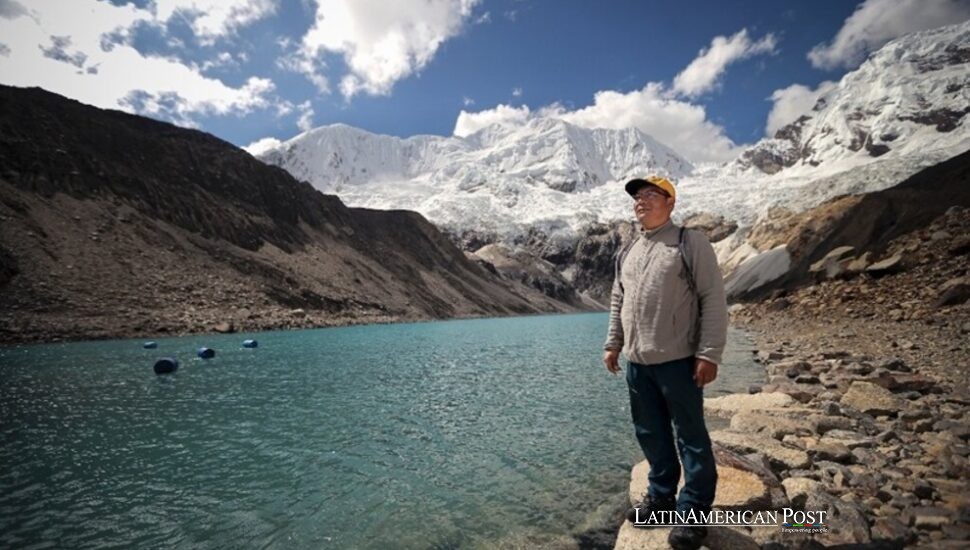

The Farmer Who Pointed a Finger at a Giant

Saúl Luciano Lliuya never wanted headlines—just peace of mind. From his small plot above the city of Huaraz, he could see Lake Palcacocha shimmering beneath receding glaciers. Each spring the waterline crept higher, and each night he pictured an ice slab cracking loose, triggering a wall of floodwater that would erase homes and memories in minutes. One evening he did the unthinkable: he sent a letter to a German power conglomerate, demanding €17,000—the fraction he calculated the company owed for its share of carbon emissions that had accelerated the melt.

Friends called him brave; skeptics called him naïve. Yet he pressed on, hauling Andean glacial data and emissions charts into a German courtroom better known for patent spats than climate drama. His request, financially modest, shimmered with symbolism: if courts could link a corporation’s exhaust pipe to a farmer’s rising lake, the era of consequence-free pollution was over.

Huaraz is beautiful the way tightropes are beautiful —balanced between wonder and disaster. Snow peaks feed a necklace of turquoise lakes that irrigate potato fields and quench a growing city. But every liter of meltwater is a countdown; Lake Palcacocha now holds four times the volume it stored at the turn of the century. One jolt—a landslide, a glacier calving—could unleash a slurry of ice and boulders powerful enough to flatten the valley.

Lliuya’s neighbors have seen warning signs: fissures in adobe walls, pastures that remain water-logged long after rain, stories from elders who remember a flood that killed hundreds in the 1940s. They backed his lawsuit not for profit but for proof that their fears mattered beyond the Andes—proof that someone, somewhere, heard the ticking clock too.

Courtroom Echoes That Refused to Die

The regional court in Hamm listened, weighed expert opinions, then ruled the immediate danger too uncertain to proceed. Case closed, at least on paper. But tucked inside the judgment was a sentence that lit up legal chat rooms worldwide: under German civil law, a big emitter could be liable for a proportional slice of climate harm if a plaintiff nails the evidence. The judges had cracked open a door—just enough for future litigants to see daylight.

Environmental lawyers pounced. If a company produces half a percent of global carbon, why shouldn’t it cover half a percent of adaptation costs from Bangladesh to Barbados? The ruling didn’t deliver damages to Lliuya, but it supplied something arguably more potent—a judicial nod that the math might someday stand.

Scientists can model ocean currents on supercomputers and track a single molecule of CO₂ from smokestack to stratosphere, yet convincing a judge is tougher. You need to show that a specific emission stream nudged a local glacier over a stability threshold, then prove the resulting flood risk isn’t merely possible but imminent. Jurisdiction tangles the matter further: can a Peruvian court subpoena a European CEO? Can a German bench dictate how high Huaraz builds its floodwalls?

Still, the playbook is evolving. New lawsuits weave satellite data, corporate disclosure reports, and climate-attribution studies that quantify how much warmer, wetter, or wilder a region became because of identifiable emitters. Lliuya’s team argued the utility in question ranked among Europe’s dirtiest and thus owned a measurable slice of Palcacocha’s peril. The court said, “Not yet,” but never said, “Never.”

Andean Stakes, Global Ripples

Glaciers in the tropical Andes shrink faster than their polar cousins. As they recede, they first flood valleys, then leave them thirsty when dry seasons stretch longer. For farming towns, that double punch—too much water, then not enough—threatens crops, tourism, and cultural heritage. Peru’s government has stepped up dam construction and early-warning sirens, but budgets strain under competing crises.

If future plaintiffs succeed where Lliuya fell short, adaptation funding could flow from corporate balance sheets into high-altitude defenses: reinforced lake outlets, avalanche barriers, relocation grants. Such a precedent would multiply across continents. Pacific islands buffeted by rising seas, African villages losing crops to heatwaves—each could present a bill itemized in parts per million.

For Lliuya, the verdict stings yet satisfies. He returns to his fields knowing he cracked the silence of powerful rooms. Activists hail the case as a spark in dry tinder; corporations brief their lawyers anew. Financial analysts whisper about “climate liability” joining wages and raw materials as line-item costs of doing business.

Meanwhile, the ice above Huaraz continues to melt. Engineers monitor lake levels; volunteers practice evacuation drills; schoolchildren learn the science of a warming world before they master long division. Somewhere, in a law office lit by spreadsheets and fluorescent glare, a young attorney references a Peruvian farmer’s claim and drafts the next lawsuit, armed with sharper data and a judge’s quiet concession that polluters might one day pay.

Also Read: Latin American Publishers Unveil Secrets for Aspiring Novelists

The Andean sky fades pink over Palcacocha. The water is still tonight, but everyone hears the glacier creak. The question no longer is whether responsibility exists, but when a courtroom will say, “Here is the proof—and here is the price.”